At left is a view down NY 5 from 2014, and still, I think a nice representation of some of the landscape Dreiser & Co would have seen between towns as they drove along Lake Erie.

This is next to the turn-out at Eagle Bay, where I took the sunset photograph in the last chapter, and a few miles shy of Dunkirk.

Looking at the book and the map, I think that after leaving Buffalo, their route would have been along what is now NY 5 for a fair amount -- though in places 5 leaves the immediate lake front-roads, which are sometimes still named "Old Lake Front Road."

But for a good many miles, NY 5 does front the lake, joining US 20 briefly before Silver Lake, then peeling off to remain near the shore.

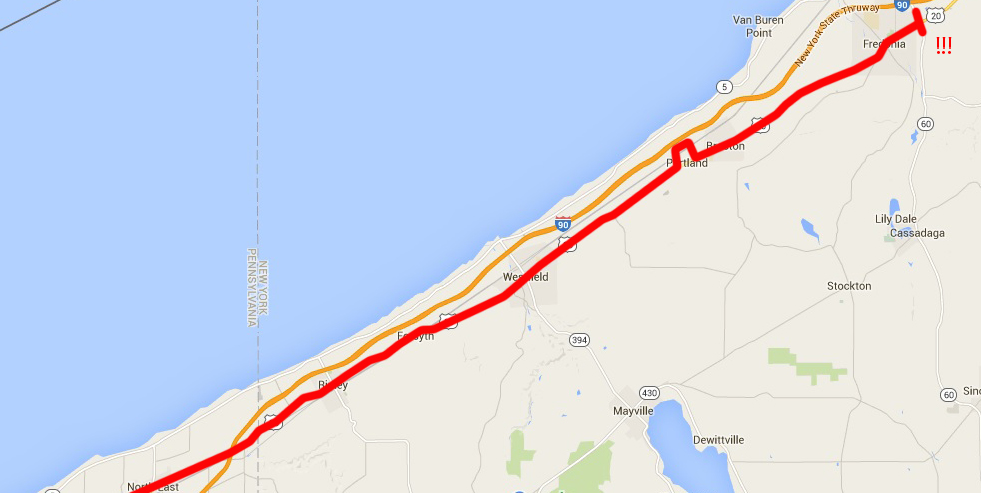

However, at Silver Lake, I think the Pathfinder remained on Main Street, and thence onto the road bed of now-US 20, and there-by gained the towns that Dreiser listed as their route brought them back to Pennsylvania: "About seven o'clock, or a little later, we reached the town of Fredonia..." and then "...Brocton, a fire arch over its principal street corner..." followed by "...Westfield, Ripley, Northeast, Harbor Creek..." This means, of course, that Dreiser & Co were never near that bit of road pictured above near Eagle Bay, but I still like the scene.

Above: Fredonia, NY, to Northeast, PA.

Fredonia scenes, after I found the turn to US 20. Once again, I couldn't see the sign, and I drove along thinking "O.K., I should have been to 20 by now -- " which of course I had crossed it and had to go back. Le sigh.

Above, at left, an old gasoline station. It had that porte cochere with stone pillars that made me think "gas station" anyway. This is one of those shots that I was surprised came out as well as it did, considering I went by at speed.

Along US 20, outside Fredonia, and the town is gone, replaced by corn --

-- and grape vines. The grapes through this region are grown not only for wine, but also for Welch's grape products, like jelly.

Fortunately, I missed what-ever these guys were going to do with the heavy equipment.

Brocton, still with a "fire arch" over the street. I think it still lights up.

Then Portland --

"Hey! Old train station!" I said, and just had to turn around so I could take a photograph. It hasn't been a functioning station for some time now, though, being home to a local historical society. Also, its site currently has no relation what-so-ever to a rail road right-of-way, which had me more than a little perplexed.

"They had to have moved it," I thought.

And this old house -- no way was I going to let this go without a stop. After taking this photo, I turned down Pecor St to see if there was a better angle (there wasn't) and to see where I would wind up, and if there was anything else worth seeing -- like another old house (not so much).

A mile or so off the highway, though, I came to the rail road tracks:

This is actually a set of three: the single track I crossed first, above at left, followed by the pair at right, and I thought "This is where the station used to sit, in between these."

A short way beyond the tracks, Pecor St went over the Expressway, and I turned left. Below, at left, the agricultural; below at right, Interstate 90, the New York State Thruway. Really, they're about 200 feet apart. Of course that's true for most of the Interstates, but -- I dunno', it's just weird sitting right in between them.

That road bent back to US 20 somewhere outside Portland, and I was West-bound again.

A mile or so down the way came on one of those serious OVERSIZE operations with the chase cars actually getting opposing traffic, like mine, off to the shoulder.

WWTT? "What would Theo Think?" Actually, he might be fascinated by the industriousness of the Americans, that we can construct something so massive, and that we can then truck it over-land with relative ease.

Shortly after that came the bridge work. At least it wasn't a detour! Beyond the stopped vehicles ahead of me, here, you can see a dump truck sitting athwart the West-bound lane; it's dumping a load of gravel to be done something with.

"The All American Theater Motel" right on the edge of Westfield. Despite my reluctance generally to stay at motor hotels like this, this one was nearly tempting enough -- or it might have been if it weren't around 11AM. A bit too early to be checking in.

"On and on...It was growing late. At one of these towns we saw a most charming small hotel, snuggled in threes, with rocking chairs on a veranda in front and a light in the office which suggested a kind of expectancy of the stranger...Franklin got down and rang a bell, but no one answered...'Do you want to try?'...I rang and rang and rang...Not a sound in response...'The blank, blank, blank, blank, blank, blank, blank,' I called, resuscitating all my best and fiercest oaths."

Sounds like a set-up for a horror film -- but that would be few decades later. On through Westfield:

Above, two houses that were most likely in Westfield in 1915, though in the middle of the night, likely gone by un-noticed. And, say sorry, but I gotta' take the picture of the CVS.

A couple more miles, and I was back in Pennsylvania. Just over the line, I noticed a rather older stretch of pavement as the now-PA Highway 5 made a swing to the left. I took the old stretch:

Again, I thought

"This could be THE road! They could'a' been right here!"

Not on this pavement, no. But still --

Grapes anyone? Just left of center can be seen the cab of a passing pick up truck over on the improved PA 5. I think the swing off the old route was to allow it to make a nearby creek on a new bridge. It also makes for a better intersection with I-90.

The trusty saloon at a trailer lot. Got no idea why, I guess it's a convenient spot for someone's trucking concern. It was certainly convenient for stopping -- again -- to take photographs! I-90 is about a quarter of a mile beyond the trees.

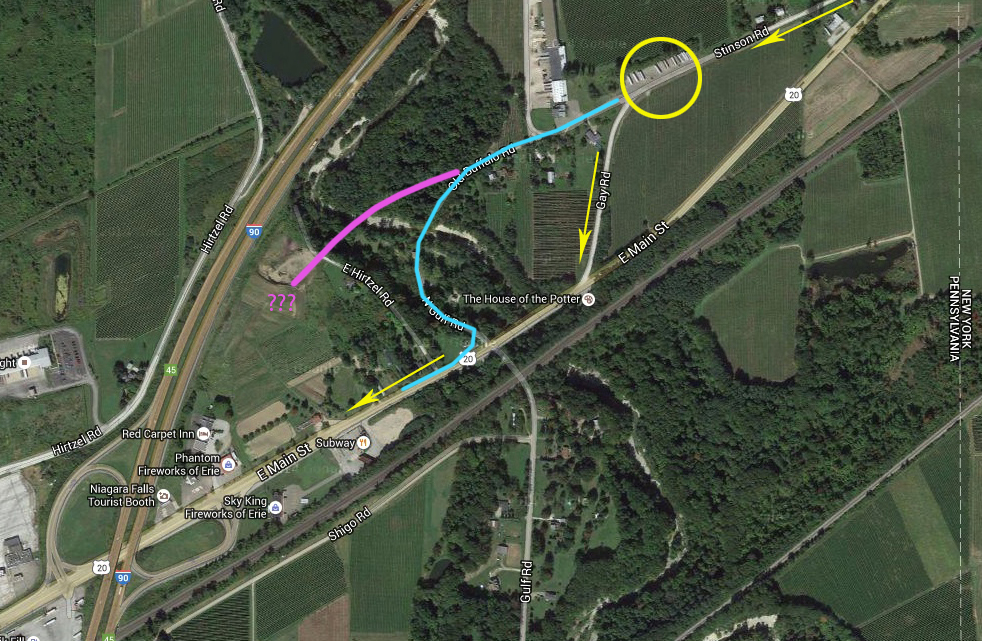

Where US 20 made that swing to the left.

The yellow arrows indicate my path; the circle is around the trailer lot where I stopped the second time for more photographs.

The blue line is where I think the road used to go: down into a pretty deep creek ravine to either a ford or a low bridge, then back up; the curve would be due to the topography -- it's a steep climb on either side.

The alternative, in purple, would have been for the road to remain on a more straight line to the creek bed, cross, and climb out - and that the current landscape on the West side has been so unutterably altered by the construction of I-90 that nothing remains of that old route now. The reason I think that might have been the case is that there is a shadow line through the trees that could indicate such a road -- or that such a road was once -- but the opposite side shows nothing of the kind, at least not any longer.

My conjecture (what a word!) is that the new bridge for US 20 came along with the improved road surface, and eliminated the bends, drops, and climbs. Whether or not this occurred at the same time as the construction of the Interstate, it also made for a better approach to the interchange.

This is one of those locations where improving the roads did effect a change in their location, as well as a change in the immediate landscape; interchanges like this always move a few tons of earth during their building. And yes, I did take a look at that road leading down the hill; I think it was private property, if I recall correctly (which I may not now). For what-ever reason I turned-about and went back to the other road for the connection with 20.

Interchange ahead! As I was shooting this, I noticed the line of clouds to the South of the roadway.

On the map above, this would be about where the left-most arrow is.

So, beyond the interchange, I shot this, because, y'know, clouds!

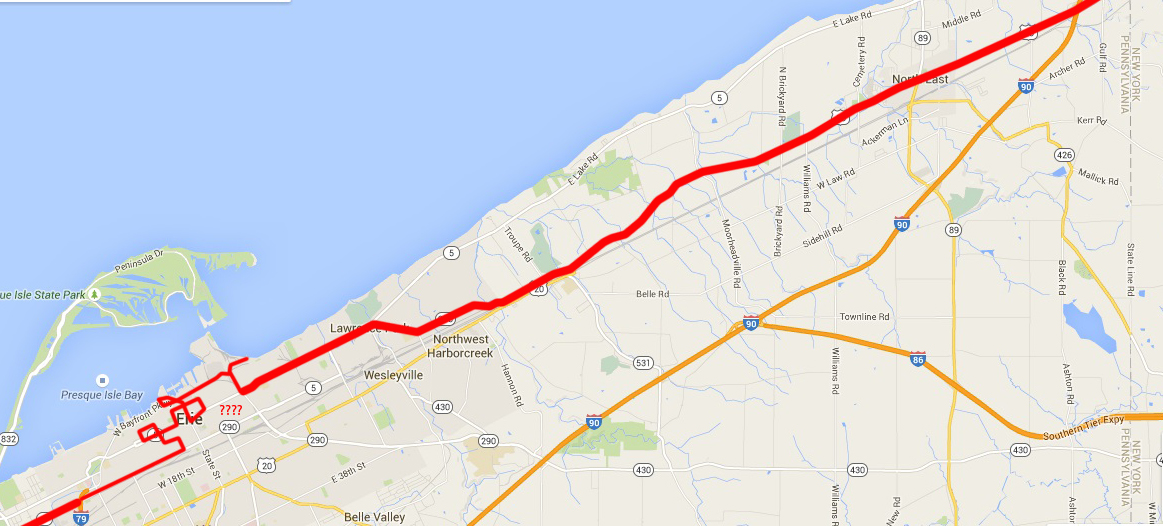

From the Pennsy state line to Erie. That jog at Northwest Harborcreek seemed like a good idea at the time: another old road that looked likely, so I spun off and took it instead of remaining on 20. The funny track through Erie barely approximates my turns around that city. Other than the bit nearest the lake, the rest is just passing indicative of the streets driven, until the route gets past the I-79 intersection way down at the bottom-left.

North East, PA. Nice house!

After the aforementioned jog off of US 20, I stopped along PA 955 for a map consult, and took this picture.

Nearer to Lawrence Park was this old Dairy Queen, which didn't look too active, sadly.

I guess Lawrence Park is a suburb of Erie -- ? It seemed a "nice" spot of town, just a few miles outside of Erie proper.

And after the left swing back on PA 5, somewhere in the mid-zone between Erie and Lawrence Park.

1912.jpg?1541207161321)

Panoramic photograph of Erie, 1912 (LOC).

This was, as in 2014, a much less traumatic entry to Erie than had Dreiser & Co, approaching in the middle of the night. As related last year, they had heard that a very bad storm had visited the city "...a few days or weeks before and that houses had been washed out by a freshet and a number of people had been killed." Between the storm damage and generally lousy road conditions, they made slow progress through the countryside.

Speed, Dreiser wrote, "...was constantly stopping it and examining the nature of certain ruts and pools farther on." They had to get out and push, or "...trample earth behind the wheels and then back up." They walked back to discover if they were on the correct road, and generally submitted to bouncing and jouncing along as best they could before finally reaching solid paving. Closer to Erie, they found a Pennsylvania State Policeman, with his horse.

" 'Which way into Erie?' we called.

'Straight on.'

'Is this where the storm was?' we asked.

'Where the washout was,' he replied.

We could see where houses had been torn down or broken into or flung askew by some turbulent element much superior to these little shells in which people dwelt.

Through brightly lighted but apparently deserted streets we sped on, and finally found a public square with which Speed was familiar."

The following morning, after a night in a hotel that Speed was acquainted with, the men got to see the after-effects of the storm.

The "freshet," as Dreiser called it, turns out to have been one of the worst disasters to strike Erie: on August 3 of 1915, thunderstorms had dumped nearly an inch of rain per hour for six hours, washing large amounts of detritus -- including small farm buildings -- into Mill Creek, which stream runs through central Erie. Some of this flotsam lodged against the entry to a culvert -- Dreiser wrote of the flotsam as a barn -- creating an inadvertent reservoir; when the culvert and the flotsam-dam blew out, the reservoir's waters descended on Erie in a literal flood. 35-40 people died, and upwards of 60 were injured.

"...the effects of the reported storm or flood were much more startling than I had supposed...Blocks upon blocks of houses washed away, upset, piled in heaps, the debris including machinery, lumber, household goods, wagons and carts...factories and homes of all kinds had been broken into by the water or knocked down by the cataclysmic onslaught..."

Above left: the scene at 328 East 4th Street; at right, the corner of 18th and French Streets.

Following the disaster of course, came the "moving picture camera men," the "picture postcard dealers," the "newspapers get out extras," and everyone got to make "an honest penny." And, Dreiser & Co made tourism out of the detritus, like so many others.

"As we cruised about in Franklin's car, looking at all the debris and ruin, I speculated on this problem in ethics and morals or theism or what you will: Why didn't God stop this flood if he loved these people? Or is there no God or force or intelligence to think about them at all? Why are we here, anyhow?...Why eight people in one house and only one in another and none in many others?...Were the people themselves responsible for not building good barns or culverts or anticipating freshets? Will it come about after a while that every single man will think of the welfare of all other men before he does anything...I am an honest inquirer...Do you think there is any such thing as justice, or will you agree with Euripides, as I invariably feel that I must?

'Great treasure halls hath Zeus in heaven,

From whence to man strange dooms are given

Past hope or fear.

And the end looked for cometh not,

And a path is there where no man thought.

So hath it fallen here.' "

As stated, my entry was not so dramatic.

The Erie lakeside, from a boat ramp near the Bayfront Parkway.

(Not sure what these used to attach to; a satellite view has them next to what had been something plainly, but what-ever it was is gone, leaving what will no doubt become a development project for some real estate company. Call it a brownfield.)

Having gained Erie, I was mildly interested in driving through a bit more of it than I had previously, and the Bayfront Parkway was as good a place to start as any, so I made a right off of PA 5 and drove for a bit, ending up at a public access with a boat ramp. But, being a public access (with a boat ramp) meant that it was on the lake, which was good for me.

Looking over the lake. Presque Isle is the low-lying, forested spit on the left half of the horizon. To the extreme left is the short, black-and-white North Pier Lighthouse, marking the end of the Erie Harbor entrance.

A closer-up view of the barge that can be seen right of center above.

Because barge! With a crane on it!

I suppose they're dredging some channel out there; I think the crane-on-barge version might be the cheaper alternative to the specifically-built dredging ship. After all, there are probably thousands of barges around the lakes that don't see the use they once did, and likely a few cranes, too, waiting for employment. A "DIY" channel maintenance assembly.

As noted with the map, I drove about Erie for some time, not really knowing what, if anything to look for, but looking anyway -- 'cause I could, I suppose.

Below left, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot complex, a sprawling campus of health care. At right, a view up State Street past the Warner Center, a restored venue like "they used to build 'em." Once upon a time I saw the public radio program Whad'ya Know performed/broadcast from the Warner -- but that's another story.

Above left: old building and power lines - because I likes old buildings n' power lines. Above right: my fellow Americans as they prepare for luncheon.

As I was heading out after lunch, back on PA 5, I passed the airport, which included this banner ad for drones. What they do for you with the drones I don't know; I suppose they do aerial surveys and such, but it just struck me as odd. And I guess I have to wonder at the drones as much as I do at the people sitting around a table staring at their pocket-sized computers.

Should we just start referring to them as pockters? Or maybe compukets? Since no one actually want so use them as telephones, why should they be referred to as such? Would they be cheaper if the service providers just dropped the voice feature?

There's probably an "app" for controlling a drone, too. You can send it a text message, and tell it to take an elevated "selfie!"

But soon enough I was out of the urban environment, and back out with the trees and grapes and what-not.

"More splendid lake road beyond Erie, though we were constantly running into detours which took us through sections dreadful to contemplate. The next place of any importance was the city of Conneaut, Ohio..."

Dreiser described Conneaut as being one of those ports that made a business of trans-shipment, with coal going out from Pennsylvania, and iron and copper ore coming in from Lake Superior. He and Booth watched ore being loaded from a rise above the town and the lake. Not realizing quite what they were watching at first, Booth pointed out that they were seeing rail cars loaded with coal being mechanically elevated and dumped: " 'I do believe those things over there are cars, Dreiser, -- steel coal cars.' 'Get out!' I replied incredulously." Further inspection proved this to be true.

What I really appreciate is the "Get out!" Seems our younger generations can't lay claim to that phrase after all, though I doubt that Dreiser would have had quite the same intonation as that of late.

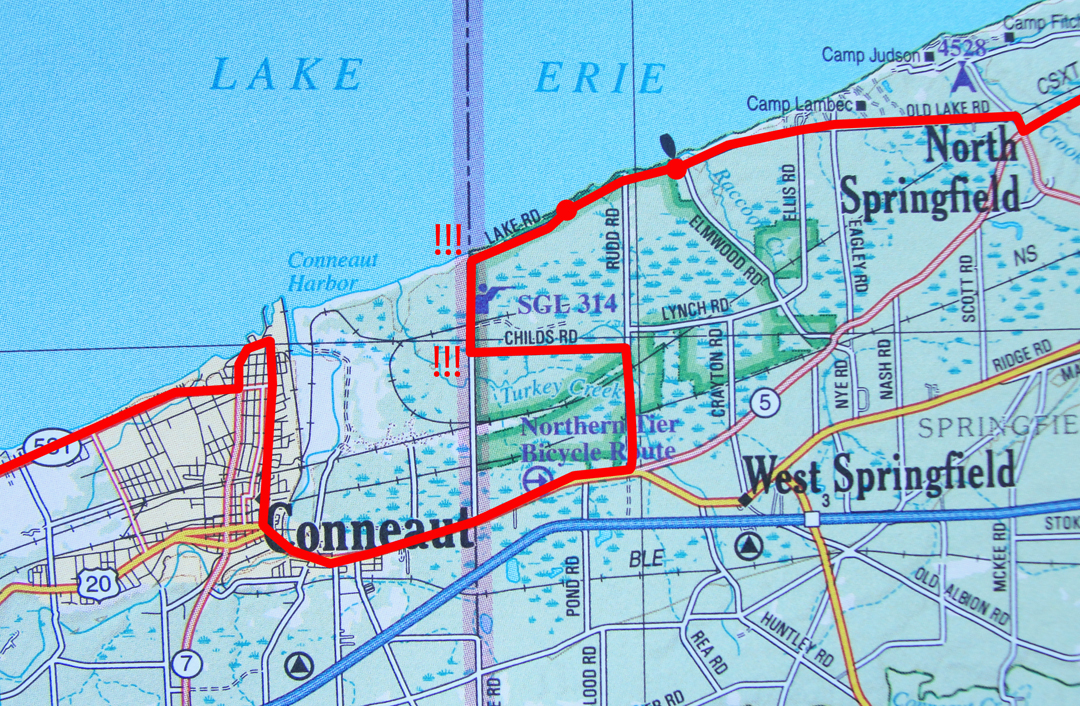

That they observed the coaling station from some elevation had me wondering if there might still be some old road that came into Conneaut above a like scene, and on the map, there was at least the possibility indicated:

Zagging and zigging off of 5 near North Springfield got me to the "Old" Lake Road, that appears to follow the most likely path, though the lack of indicated roadway once across the state line into Ohio left me a bit mystified. As it happened, once into the SGL -- State Game Lands -- the last of the lake road restricts itself to Pennsylvania only, and then quits vehicular access at Childs Road, so I was forced to return to the highway and make my way up to the harbor area. Not quite the elevation or perspective I had wanted.

Looking for the Lake Road, and hence the title of this chapter. Here, though I think I found it!

At a distance off of the highway, there was Raccoon Park, between the road and the lake, which seemed ripe for a photograph or two. On the map above, it's indicated by the little boat, as in "= boat ramp."

I don't know why the lake water in the immediate area around the park is that paler color; there are plumes similarly tinted in satellite imagery, and it may be outwash from creeks carrying sediment out.

I almost stated "out to sea," which isn't quite right, but to look over this body of water -- it's kinda' hard to tell.

The slab structures are jetty constructions, I guess to keep the shore from moving? 'cause there's so much current through here? ??

Once into the game lands, the Old Lake Road became the Old Dirt Lake Road. This stretch of roadway may never have seen pavement!

A short way past Raccoon Park there was a hunters' access of some kind -- which was a mowed path to the bluff overlooking the lake, with official notice to keep vehicles off. I didn't see why such would be needed, but it afforded a view of the lake, so I walked out to the edge. Above, centered on the horizon, is the lighthouse at the harbor entrance at Conneaut, still a few miles distant.

The saloon, just inside the State of Pennsylvania. It doesn't show well on the map, but the road is, in fact, just "this side" of the line with Ohio, as evidenced by the marker set out on the line of demarcation, as seen below:

And I was in the State of Ohio to take this photograph! Just like that! I'm in Pennsylvania! I'm in Ohio! (hop hop). The inscription on this small obelisk reads:

"Erected in 1881 by a joint commission appointed by the states of Pennsylvania and Ohio to re-survey and re-mark the boundary line as established in 1786."

After dodging out of the Game lands, and back to US 20 headed for Conneaut: at left, below, an old commercialized building of some kind that could use some rehabilitation; at right, cars for sale at another old gas station, maybe -- on the edge of town.

Entering into Conneaut proper, was this building, which looks like it might have been a hotel, once upon a time.

I think maybe the trees have grown up in the last hundred years!

At right, a view of a collier basin, a short distance off the lake. Below, a collier taking on its compliment of cargo.

Here, piles of ores, similar to what Dreiser would have seen in 1915, though I think somewhat diminished in size, for, as he put it there were: "...great long hills that it must have taken ships and ships and ships of iron to build."

This is more like a couple ships.

In frame at the left of the photo above and in frame at bottom right here is a water treatment plant. Beyond that is small boat marina, giving on to Conneaut's harbor area.

This seems to be the way along the lakes: when the industrial economy plays down, go for the tourist dollars. I guess it works for some folks; I saw a fair number of private boats in quite a few harbors.

"...this northern portion of Ohio is a mixture of half city and half country, and this little city of Conneaut was an interesting illustration of the rural American grappling with the metropolitan idea. In one imposing drug or candy store (the two are almost synonymous these days) to which Franklin and I went for a drink of soda, we met a striking example of the rural fixity of idea, or perhaps better, religiosity of mind or prejudice...In most of these small towns and cities...total abstinence from all intixicating liquors is enforced by local option...they get what are sometimes called near-drinks [like] 'Sparkade'...a feeble watery thing..."

The young woman waiting their table refused to try the Sparkade when Dreiser offered her a taste.

" '...anyhow, I don't think I'd care for it...Our church is opposed to liquor in any form.' She made a contemptuous mouth.

'There you have it, Franklin' I said to him. 'You see -- the Church rules here -- a moral opinion. That's the way to bring up the rising generation -- above corruption.' "

Above left: call them the "Shoreline Specials." I can't speak to the other major coasts of the United States, but along the Eastern Seaboard are many similar structures where there is a "view" of the water, whether for seasonal rental or for year-round residence. They seem to have a bent for the sliding-glass-door-and-deck "combo" as here, and little to nothing to recommend them otherwise, architecturally speaking. Above right are, perhaps, the "Union Dollars Houses:" mid-20th Century dwellings likely bought by the longshoremen who worked those lake boat-slips on the harbor and looked forward to taking a vacation with the wife and kids in their brand new car, which came from Detroit of course.

"Beyond Conneaut we scuttled over more of that wonderful road, always in sight of the lake and so fine that when completed it will be the peer of any scenic route in the world, I fancy. Though as yet but earth, it was fast being made into brick."

Leaving Conneaut, I went West on Ohio Highway 531, tracing along near the lake shore. No dirt, no brick, no longer, and the "scenic" had been overtaken by houses in many places.

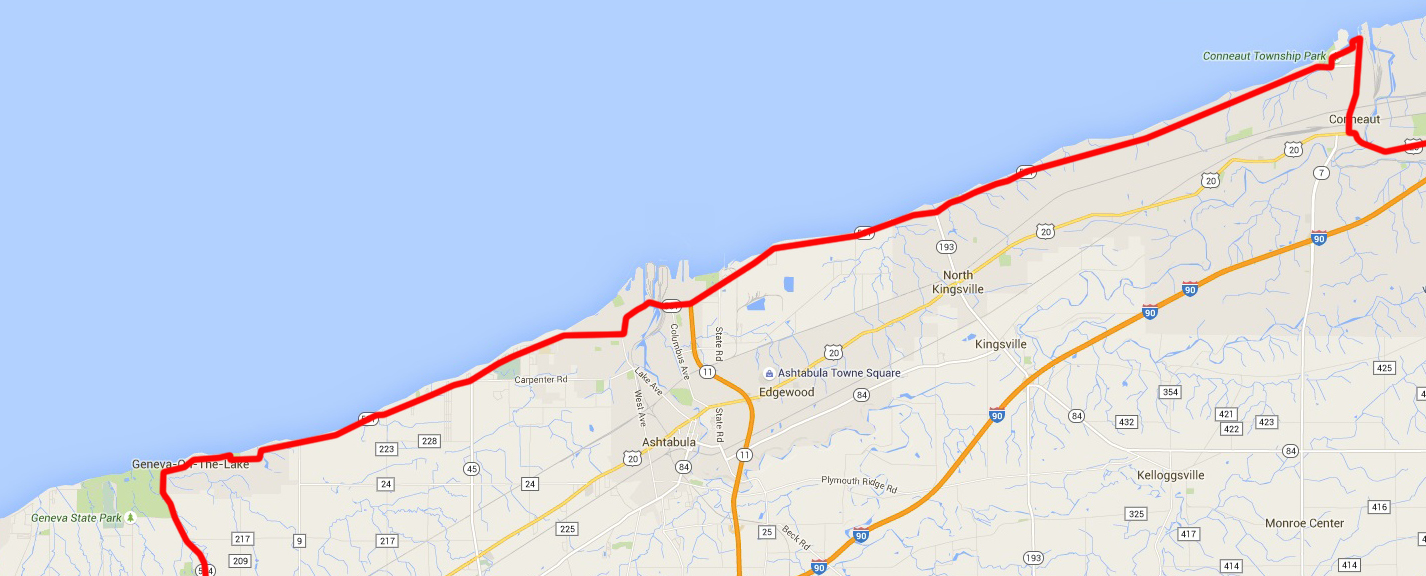

After the Game Lands, to Geneva-on-the-Lake.

Bob Dylan refered to Ashtabula in his song "You're Gonna' Make Me Lonesome When You Go." The first time I heard it, as sung by Madeleine Peyroux, I wasn't sure whereinthehell Ashtabula was, even though I was in Pittsburgh at the time. Well, I know now!

As in Erie, so here on the way to Ashtabula: an old building with power lines! Though with this building, it was "old building from which the power once emanated:" part of a larger complex of electrical generation belonging to First Energy's Ashtabula campus.

Below is their main structure, just a little way farther West:

Nearer to Ashtabula, the traffic on 531 came to a halt. I had no idea why, but I got off this shot of some older homes.

"Then came Ashtabula with another such scene as that at Conneaut, only somewhat more picturesque, since the road lay on high ground and we had a most striking view of the lake, with a world of coal cars waiting to be unloaded into ships..."

And what do you know, but I had a similar view; in this case, from a used car lot, which is both appropriate and ironic.

Again, the resurgence of the flora in the area. I really can't imagine that there was quite so much "green" in the vicinity when Dreiser & Co passed by here.

OH 531 here was, indeed, on "high ground," having come to Ashtabula on a bluff, and traversing a bridge over the rail road tracks seen above. The car dealership whose lot I "borrowed" sat atop a wedge of embankment at the foot of the bridge.

After the road dropped down to the ancient flood plain of the Ashtabula River, I saw this impressive conveyor crossing the river, connecting coal fields.

And "discovered" why the traffic on the highway halted: a lift bridge. Naturally, there are private boats on the river. Though I didn't see more, there are, on the map, several marinas along the river, hosting numerous small craft.

Beyond the bridge was a tidy little business district, with new retailers in old buildings.

One of those retailers, the Harbor Perk, got my business. 'cause, y'know: coffee! As was common on this trip, I had to turn about and come back to get to the coffee.

Having procured that dark precious liquid by which I measure my days, I had to wait for traffic to clear -- 'cause, y'know: lift bridge!

And coming around the block from the neighborhood of the harbor, I turned again on to 531, which was then back well above lake level. Ashtabula has grown out from the older areas, and of course now has the ever-popular Retail Area.

Like y'do.

Hwy 531 leaves Ashtabula headed West toward Geneva on the Lake, though -- as pretty muchly anywhere there is water -- it's hard to say just when one has crossed the town line; anywhere there is water there are residences, unless the Lake Road is close enough to the water to prohibit the land being platted and sold off for construction, as here:

I can easily imagine that someone would try to sell this narrow swatch of dirt, though.

"And after Ashtabula...came Geneva-on-the-Lake, or Geneva Beach, as it seemed to be called -- one of those new-sprung summer resorts of the middle west, which always amuse me by their endless gaucheries and the things they have not and never seem to miss. One thing they do have is the charm of newness and hope and possibility, which excels almost anything of the kind you can find elsewhere."

I did hold out a tiny little bit of hope that Geneva on the Lake would still have some of that "summer resort" charm of which Dreiser wrote. I knew that it was at best a vain hope, for where in the world would I find a resort with the atmosphere of an hundred years prior? But I must admit that the description of the place Dreiser sketched appealed to me in its contradictions, as much as it appealed to him.

Geneva on the Lake, 1913, (LOC).

"America can be the rawest, most awkward and inept land at times. You look at some of its scenes and people...[and] wonder why the calves don't eat them. They are so verdant. And yet right in the midst of a thought like this you will be touched by a sense of youth and beauty and freedom and strength and happiness in a vigorous, garish way which will disarm you completely and make you want to become a part of it all, for a time anyhow."

Are we not the same today? Dreiser certainly seems to be describing the very things which we would still celebrate of ourselves as "American," as much now as in 1915, whether celebration is warranted or no.

As he described the young people of Scranton (for it is the young he notes often) here, too, are they out parading in their summer finest, or at least what they believe to be the finest. The women in contrasting colors or bold black and white, the men in summer suits or sailor shirts and tennis shoes, all of them with a "...jocular, inconsequential air." He contrasts the Europeans who "...seek a kind of privacy..." in summer, while in Ohio it was "...lawns, doors and windows...open to the eyes of all the world." People engaged in "Croquet, tennis, basketball..." -- basketball! -- or lounging about on "...swings, hammocks, rockers and camp chairs..." "All the immediate vicinity seemed to be a-summering, and it wanted everyone to know it."

They were for the most part lively, friendly, and engaging, though he felt many were "shallow." What Dreiser describes of Geneva Beach is the description of America at a point along its continuum of change, when there were people enough with means to take a vacation on the lake, when magazines and movies were coming of an age to assert a particular influence on manners and dress, when the population was doing its best to make sense of it all. Barely a generation prior only the wealthy would remove for a summer on a lake, and most of the people were still employed at agriculture or manufacturing; a middle class with leisure time as we would recognize it had only been in existence for a couple decades. In Ohio, Dreiser was watching people, ordinary folk, negotiating a world that was, for many of them, a new world.

"Well, that looks promising," I thought as I

drove under this sign at the edge of town.

The road, once under the sign, veered left, then right, making a course correction for some reason before approaching the summer season area nearer the lake. When I saw a sign noting "Old Lake Road" to the right, I thought "That's for me!" and turned that way. A few blocks down was a city park.

I guess I'm not the only person to ever stand there and wonder "O.K., but where's the beach?" because the Ashtabula County Civic Development Corporation had put up a placard with that very question posed. Including some old photographs (as below) of summer life in Geneva on the Lake that date from early in the 20th Century, the placard informed the reader that Lake Erie has washed the beach quite away, and that land loss has caused the Lake Road to be re-routed as the earth disappeared.

Why this loss of sand is attributed to, among other things, the regulation of water levels for navigation, or to the introduction of a breakwater on the West side of town for a marina. However it occurred, Geneva Beach has significantly less beach now than it did, though enough for local lodgings to still advertise beach access to their guests.

As can be seen in the photo above, there are either in whole or in part a series of short breakwaters along the shore here, clearly placed in the hope that it would keep the beach in place. Too late, most of those remedies have proved to fail.

I've had discussions of these old buildings with people through the years, and what I've concluded is that, imitative as they might have been when they were new (and as boring as they might have appeared to Dreiser -- as when he's complaining of Scranton's architecture) they were erected with the idea, or ideal, of aspiration.

Though copying New York or Chicago, or even Indianapolis, the notion was to reach a little higher, to create a world more than had existed for the first several decades of the Republic. The physical embodiment of the Progressive movement, perhaps?

Looking West from the park, up the remaining Old Lake Road.

The light line in this satellite view shows where the road would have gone, more or less, when there was something there to hold it up. It is also clear that there is very little beach left, reduced to what looks like 25 or 30 feet, where the beaches were described as having been 60 feet deep below the bluff. As with most of the shoreline, the lake's level is lower than the land by some 20 or 30 feet.

As I drove in, I passed several lodging establishments, newer and older, larger and smaller, and their appearance did not bode well for my vain hopes of "charm," as they fell into the usual categories of bland boxes, larger or smaller. Leaving the park though, I still kept my sights on some vestige of the old Geneva.

There were some old buildings, but they weren't, in the main, "that old;" more middling old, probably post World War Two structures that replaced anything that would have been here in 1915. And, with the retreat from the shrinking beach, if any of the oldest resort houses had survived, they certainly would have been taken down by the 1970s.

Of course the middling old have already been around long enough to have been adapted for newer businesses. So my vain hopes were replaced by a sigh of resignation.

I may simply have to concede that I have an unreasonable want for towns like Geneva on the Lake, as I was struck more with the sameness of the place. It appeared that, as Dreiser complained of towns before, they have merely copied with no eye to setting the place apart with imagination; the usual has won out, and instead of "getting away from it all," it has become another locale to do the 'same ol' same ol'," though here with the lake as a backdrop.

I have heard the conversation in movies and on TV (sorry I can't cite, so don't ask) between the man who believes that "chain" stores are a bad idea, and the burgeoning entrepreneur who claims that people want the familiar where-ever they go. I don't know if such a debate ever actually occurred, but the conclusion seems plain enough.

Mr. Howard Deering Johnson had, by 1940, "...about 125 locations on highways shoulders from Maine to Virginia..." while Williamson S. Stuckey Sr. was building his own snack and trinket empire from the South outward. I'd be lying through my teeth if I didn't readily admit my own buy-in on the familiar, but that doesn't mean that I won't be a little sad to see some Strip like this, so like other strips.

There was the consolation of this house, though, which may not have had any lake frontage in 1915, but I think it does now. And a picket fence!

After Geneva on the Lake, the Lake Road, on the map, became an incomplete trail, a street among others in housing developments with names like Atwater Fortunato or Scarsbrook on the Lake (really? who thinks up names like these? Does "Atwater Furtunato" translate as "big money guy on the lake?"). I simply had no desire to jog back-and-forth when all I might see is one house after another, and at a guess neighborhoods to which I would never likely aspire to residence. So I made for US 20 West again, and when given the option of Ohio Highway 2 -- the Lakeland Freeway nearer to Geneva, and the Cleveland Memorial Shoreway where it crosses the Cleveland waterfront -- I took that, too. So much for seeing Cleveland.

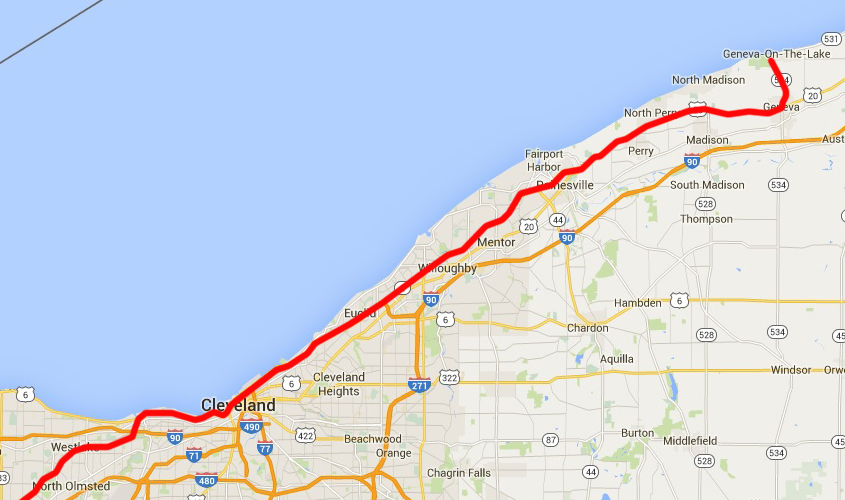

The route of the saloon past Cleveland.

Dreiser & Co, on their way and somewhere West of Ashtabula, came upon a series of impressive bridges which appearance prompted Booth to make a drawing even though it was night time, and raining, and Dreiser had to hold up the coat tails of his mackintosh to shield the paper and Franklin's head. I have no idea where a rail road viaduct, an iron road bridge and a trolley bridge might have been. If the old saw about "the exception proves the rule" has any meaning, then the way that the Lake Road has been lost between Geneva on the Lake and Cleveland points to my assertion that roads usually remain in this country.

If I had been honest with myself, I would have accepted that I had by Geneva Beach reached the point when my brain refused to be all that co-operative. I should have, by this point in the journey, known that I had a limit to my being able to think beyond simply keeping the car moving forward, but instead I doggedly pressed on, wanting to by-pass Cleveland and get on to Elyria and Vermilion. Stubborn, I guess. But the sun was still well up over the Western horizon, why would I not continue?

I think now, in retrospect, that I would most days slip into the old habit of driving long distances, as I had noted in 2104. There comes an hour when I just drive to get -- well, somewhere -- and the imagination to relate to the world beyond the auto glass diminishes to a greater or lesser degree. Ah, well --

The Pathfinder was held over for the night in Painesville; I went up the expressway.

On Ohio 2, and the beckoning sign of FOOD if you fancy.

And what I thought of as "The Great Wall:" a sound barrier that ran alongside the Lakeland from somewhere West of Painesville to near Cleveland, over 20 miles -- with breaks for interchanges and overpasses. I would, from time to time, look about and wonder if it had disappeared -- following a change of township, maybe -- but then I would see it again. And again and again.

Not at all directly related to this journey, nor to Dreiser & Co on their trip, but related to that problem of clashes in the urban environment: for a few years I lived in South-East Virginia, the area called Hampton Roads -- for the last 20 years or so anyway -- and once referred to as Tidewater, Virginia. The cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach are the municipalities on the South Side of Hampton Roads, and they are home to the largest installations of the U.S. Navy. The Norfolk Naval Base saw the introduction of jet engine aircraft in the 1950s, and the near-by neighborhoods soon complained of the noise. Since the city and the base grew up with some simultaneity, not quite embracing each other as they enlarged toward each other's precincts, it should be no surprise that complaints of aircraft engine noise were heeded by the naval command and the jet fighters moved.

To reduce the nuisance, the Navy purchased a huge swath of acreage in what were then still truck farms East of Norfolk, in otherwise unincorporated Princess Anne County. The thinking was there just weren't enough inhabitants for cause of concern; most of the people who might complain were miles away at the Virginia Beach Oceanfront.

By the late 1990s, of course, when the county had long since been incorporated as the city of Virginia Beach, a greatly expanded population had surrounded the Naval Air Station Oceana. Houses and apartment complexes grew up and nearly brushed the fence-line. But the planes still flew, and if anything, they were louder, so the near-by residents complained of the noise.

Living in Tidewater (I still thought of it as Tidewater -- call me old fashioned), I would watch sometimes as the F-18s manouvered over the Lynnhaven Mall, over the apartments sprawling in that vicinity, and thought that if ever one of those planes crashed away from the base -- as they do sometimes on the base -- it could be a terrible mess: jet fuel and balloon-frame apartments should never come together. That did happen a few years ago, with a small apartment block destroyed. Fortunately, there were no fatalities.

What's this got to do with the Great Wall? Something about how we deal with the problem of "my back yard," as most often referred to in the catch-phrase "Not In My Back Yard" or simply NIMBY. We want the Navy pilots to practice, just NIMBY; we want an expressway, just NIMBY; many of us want light- or heavy rail transit for commuters, just NIMBY. You get it, right? It just still amazes me sometimes how there's always someone else who should be inconvenienced by our conveniences; never minding that there's scant little left where conveniences can be built that won't inconvenience. Of course the Navy didn't ask for anyone to build so damn close, but that's what happened. And the only place things like expressways or rail transit are wanted or needed are by their very nature going to be in places where someone gets shoved aside or someone will hear noise. Which puts me in mind again of Robert Moses, but that's still another story.

ANYway, back to Cleveland.

Near the interchange with Interstates 90, 77, and 71, with downtown in the distance.

"...we set off...over the shore road to Cleveland, which proved better than that between Erie and Painesville, having no breaks and being as smooth as a table. At one place we had to stop in an oatfield where the grain had been newly cut and shocked, to see if we could still jump over the shocks as in days of yore, this being a true test, according to Speed, as to whether one was in a fit condition to live eighty years...When it came my turn to do it, I funked miserably...so badly that I felt very much distressed...

In the suburbs of Cleveland were being built the many comfortable homes of those who could afford this handsome land facing the lake...Here, as I could tell by my nerves, all the ethical and social conventions...were being practised [sic], or at least preached. Right was as plain as the nose on your face; truths as definite a thing as the box hedges...If I had had the implements I would have tacked up a sign reading 'Non-conformists beware!...' "

Cleveland, circa 1911 (Shorpy)

Cleveland, 2015.

"Don't smile, dear reader. I know it sounds like a joke. In the face of the steady settling of all powers and privileges in America in the hands of a powerful oligarchy...the feeble dreamings of an idealist...are foolish; but then, there is something poetic about it, just the same...We always want to help the mass, we idealists...all that we have to do is to clear away the greed of a few individuals who stand between man and nature, and presto, all is well again. I used to feel that way and do yet, at times. I should hate to think it was all over with America and its lovely morning dreams.

First Energy Stadium.

And it's fine poetry, whether it will work or not. It fits in with the ideas of all prophets and reformers since the world began. Think of Henry George...dying in New York in a cheap hotel, fighting the battle of a labor party...W.J. Bryan, with his long hair and his perfect voice...wishing to solve all the ills of man by sixteen to one...'Potatao' Pingree, as they used to call him, once governor of Michigan, who wanted all idle land...turned over to the deserving poor...Hart, Schaffner and Marx with their minimum of two dollars for every little seamstress and poorest floor washer. What does it all mean?

Cleveland City Hall

I'll tell you.

It means a sense of equilibrium, or the disturbance of it. Contrasts remain forever...now and then when the contrasts become too sharp or are too closely juxtaposed, up rises some tender spirit -- Isaiah, or Jeremiah, or Christ...Robert Owen, or John Brown, or Abraham Lincoln...It is wonderful...those dreamers and poets and seekers after the ideal!

The Probate Court of Cuyahoga County.

"...of a universal panacea there is only a dream -- or so I feel. Yet it is because we can and do dream -- and must, at time -- and because of our dreams and the fact that they must so often be shattered, that we have art and the joy of this thing called Life. Without contrast there is no life. And without dreams there might not be any alteration in these too sharp contrasts....Let us sing over Life as it is. These tall, poetic souls -- are they not beautiful? And would you not have it so that they may appear?"

Above left, and below, old and new buildings near the Cuyahoga River. Above right, a view of the river with lift bridge and Superior Ave viaduct, circa 1912.

The building to the right had a sign for the Van Rooy Coffee Co., a coffee, tea and spice importing and roasting business. 'cause, y'know, coffee!

Dreiser, following his exposition on contrasts and art -- we probably would have loved or hated each other for sharing such ideals -- came back to his interest in Cleveland.

As had Buffalo, Cleveland had been twenty-some years prior a stop of a sort as he tried to figure out what to do with his life, and he remembered coming into town and marveling at its "...dirty and raw and black, but forceful..." energy, and the manses of the wealthy on Euclid Avenue.

In 1915, the company had breakfast, looked on at the "...most stately and perfect featured young woman cashier [who] claimed our almost undivided attention..." and looked in on the Hollenden Hotel (at left circa 1900 [LOC]) where Dreiser once sat as a "chair warmer" waiting to take up stories for Cleveland's Plain Dealer.

They also inquired of the best roads to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and were informed to proceed to

"...Elyria and Vermilion, and so on through various Ohio towns to the Indiana line...I argued that we should go by the lake anyhow, but somehow we started for Elyria -- or 'Delirious,' as we called it."

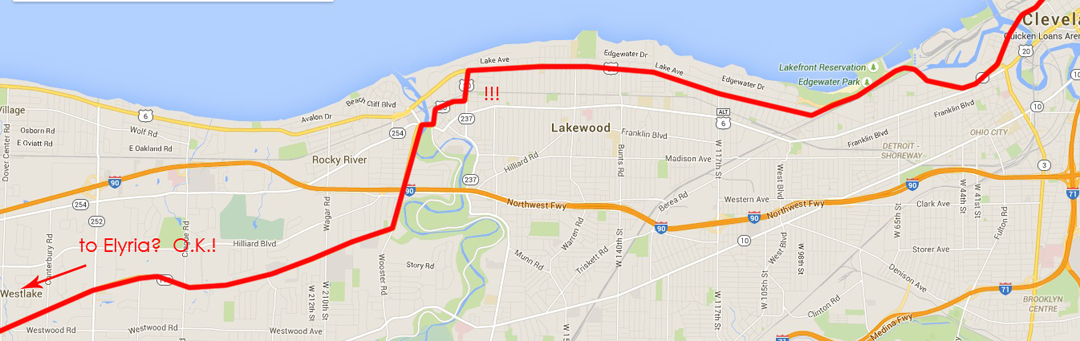

Looking at this route on the map, I'll admit it seems dubious. Elyria and then back to Vermilion? What?! Oh, well, if that's the way, there I go. "Delirious" may have been apt.

Ohio 2 as an expressway quit soon after crossing the Cayuhoga River, and I found myself in the city of Lakeside, which was, I think, what's called a "tony" area. As at right: wanna buy a house? "If you have to ask..."

Some distance farther along the leafy Clifton Blvd., I saw this old, and decrepit, structure which looked like it might have been old enough, though it turns out to have been built almost ten years later.

It's the Fifth Church of Christ - Scientist, built in 1926, which would have likely caught Dreiser's attention, as he had taken an interest in that sect, or at least some of its tenets. This building is scheduled for demolition, being of such dilapidated condition that even the Cleveland Landmarks Commission signed off on its going away in favor of a block-full of new construction. The initial consideration led to agreements in 2014, and may actually proceed this year, though some interest has been voiced for the reclamation of some of the architectural elements.

Above: some of the older and newer buildings alongside US 20/OH 113 in the Rocky River and Fairview Park areas. The shot at right could be almost anywhere, and reminds me of a lot of flat towns in New Jersey.

After some more weird turns, I wound about to gain Ohio 113, a fairly straight shot to Elyria. As Elyria looks, on the map, to be outside the urbanized areas about Cleveland, I kept waiting for the corn, or soy beans, or wheat, or something. Maybe they were there, but if they were, they were beyond the Zoned Commercial that littered the edge of the road nearly the entire distance from Lakewood on down.

As Dreiser has no mention of anything in particular between Cleveland and Elyria, only that it was "the flat lands of Ohio" as described as the chapter heading, I was only just guessing at this route. But it seemed reasonable to look at, on the map. On the ground, it was:

Looking at a "Leading Economic Indicator:" more new houses, plus playing fields.

Somewhere after the new housing development, I saw a sign or an intersection for something that indicated that I had, after all reached Elyira. What? How'd that happen? Somewhere in between all the roadside things, I had passed over enough road to leave the lake behind -- and now I would go back to it.

I have even less to say about Elyria than Dreiser, I think. It struck me as another here-to-fore well-to-do city of modest size that might be looking for a reason to go on existing. Given that it was a Monday evening, and well after day-time business hours, perhaps it was reasonable that the downtown looked unoccupied, but like so many places the downtown seemed to be the epicenter of a municipal identity crisis. I could be entirely unfair in this assessment; as noted above, I was doggedly pushing on in the lowering sunlight, wanting to make it through and beyond, to get on to Vermilion, though there was really no good reason why for that.

After a little time winding through, I found my road out, and was back in the mostly agricultural with dollops of residences landscape. I had nearly got to the point where the thought of taking photographs had passed, but then I would remind myself that if I wasn't going to bother with the camera, I might as well just quit this thing entire and go home. Other than the general directions, Dreiser & Co were left to their lives of an hundred years ago.

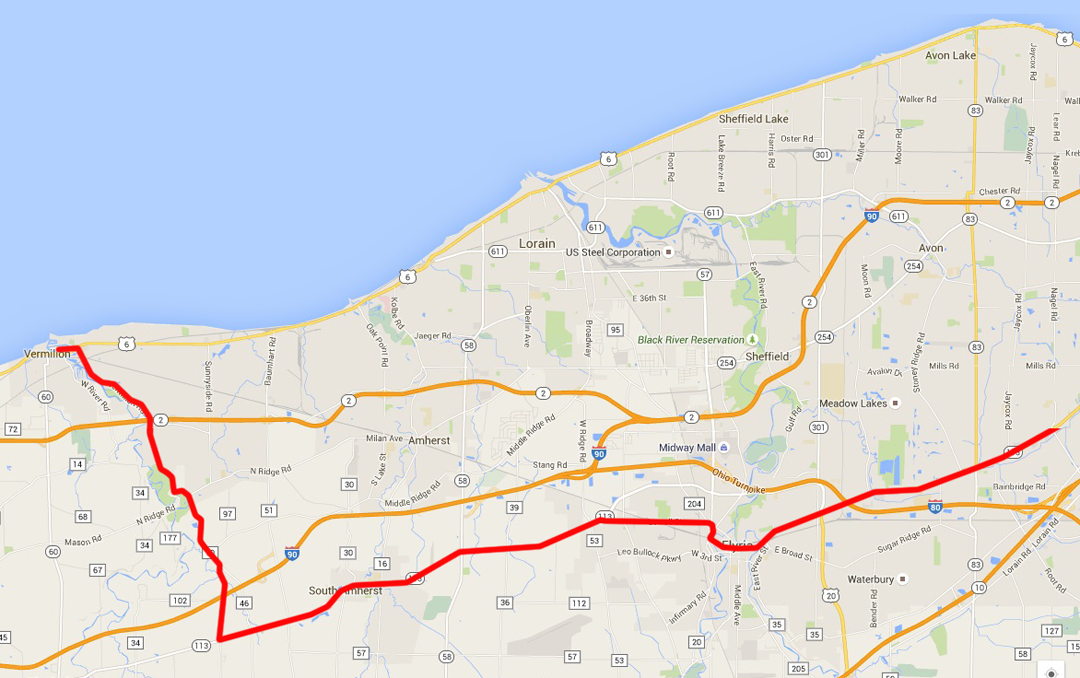

After Cleveland. I too, wondered at the direction of Elyria-to-Vermilion since the now-US 6 follows the shore as Dreiser wished to go, but whomever recommended the Southerly passage was probably convincing as to the condition of the roads. Well, so the Pathfinder, so my saloon. Even without specifics. Like a few other places prior to this, the choices of road looked limited within what parameters I had to work. The resulting way is shown above.

After a missing a turn or two, I found Vermilion Road, which rolled up through the great Mid-West mixed-use lands with their not-quite cheek-by-jowl old farmsteads and much later "ranch" variants on the house. The so-named pavement did, after all, take me right up to Vermilion, near the lake, and I had no idea what to do next, really. O.K. and -- ? So I found my way to a street close to the water and finally stopping at Sherod Park for a stretch and a cup of coffee. There was here a little stretch of beach off of which a few people were sporting with jet skis.

It was looking at this fellow, who had just alighted from his personal water craft, that I realized that the lake got deep fast. He's just not far off the shingle, and up to his chest.

When I had whiled away perhaps twenty minutes or so, I pushed on. I knew by this time that I must needs find lodging for the night; the day was going and my waking mind was going with it. At first I continued West, but the near-lakeside did not look promising, being summery resort-stuff for the most part.

Having gone for some 10 or 15 miles to Huron, I thought "All right, this is stupid." Seeing a sign that Ohio 2 was but a short distance away, I put the saloon back on the expressway and back-tracked with my eyes open for the placard informing me of a near-by motor hotel. I came upon that just south of Vermilion, which seemed as good a place to start the following morning as any, so Holiday Inn Express got my business.

It was good to stop again.

Tomorrow: the last legs: a visit to the "Roller Coaster Capitol of the World," the passage of Defiance and Hicksville, and Warsaw at last!