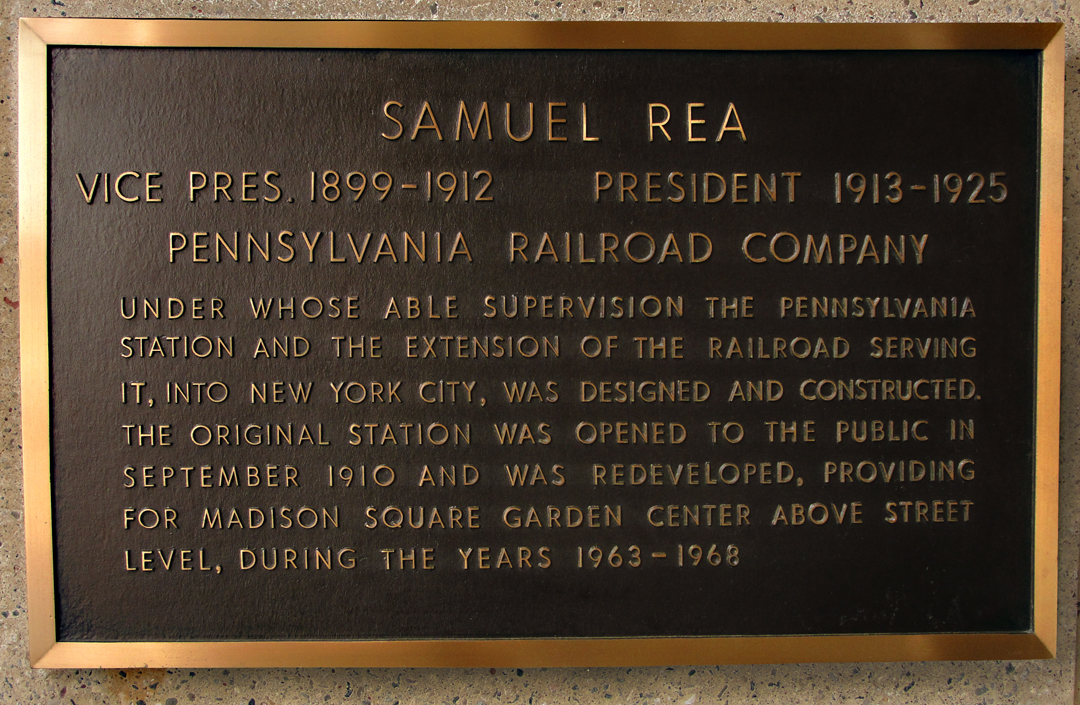

Samuel Rea: the man who looked at a river and saw a tunnel and a really big train station.

What the above plaque fails to mention is that the "extension" of the railroad was made possible by means of the pair of "North River Sub-Aqueous Tunnels" that allowed the heavy trains of the PRR to go under the Hudson River (still called the North River in 1910).

Those tunnels were part of a larger system that the Pennsy built out in those early years of the 20th Century; besides allowing train traffic to make the trip from New Jersey to New York without putting cars on ferry boats, there were also tunnels extending to and under the East River that allowed freight and passengers to continue to Long Island and Boston without having to disembark.

Those tunnels are all still in use: New Jersey Transit and Amtrak use the Hudson crossing, while Amtrak and the MTA's Long Island Railroad use the East River crossing.

Other tunnels existed under the North, or Hudson, River: what would become the PATH train tubes allowed for subway transit between Jersey and lower Manhattan at the end of the 19th Century, but by comparison those trains and tunnels are small.

The Holland Tunnels would be opened for auto traffic in 1927, the George Washington Bridge in 1931, and the Lincoln Tunnels in 1945 (delayed by World War II). Other than the out-dated Tappan Zee bridge far upriver from Manhattan, these are still the only fixed means of egress trans-Hudson until one travels quite some way north. Commuters and tourists also have the option of taking a water taxi from several points on either side of the river.

As part of this massive expansion into Manhattan, the PRR made plans for a huge passenger station, and purchased the real estate necessary for what would become a city block of structure.

Pennsylvania Station as it was before the Great War, exterior and interior.

These aren't my photos; unfortunately I don't have a time machine. Yet.

To ensure that the tunnel approaches to the station and the platforms would be built readily, the Pennsy bought over 3 city blocks worth of property and started digging stright down. Part of the cost was planned to be restored to the company by selling what are now called the "air rights" over the trackage: above the right of way, other buildings could be constructed. At the time, the only taker was the U.S. Postal Service, which put its New York Main Post Office on the block just west of 8th Ave.

The Post Office, while still accepting mail in its lobby, has since been suplanted by a facility in the Jersey Meadowlands that is even bigger than this block-sized structure, which leaves the future use of this property in debate. There was once a plan to expand rail travel under and inside the Post Office, but that is on hold at best.

Beyond the Post Office, one other building eventually was erected, and a huge swath of ground was turned into the marshalling yards for the Long Island Railroad, sending the day's consists under the building and down on to the platform level under Penn Station.

During the post WWII era, Robert Moses was still in charge of New York City's Parks Department, and continuing to tear down and rebuild the metro area to make it more "car friendly," among other things. In part due to his and others' emphasis on automobiles and the burgeoning suburban landscape, passenger rail travel declined. Part of that resulted in the decline, too, of Penn Station, and the grand structure was torn down in the early 60's. On the site, while there is still a Penn Station serving rail traffic, the "air rights" were occupied by a new Madison Square Garden and an office tower that is home, among other businesses, to the McGraw-Hill Companies.

Madison Square Garden, one of the most used venues in the country, hosting basketball to

rock 'n' roll and country.

The 7th Avenue entrance to the office block and Penn Station, which is now at the first basement level. Of the stone sculptures that once adorned the facade of Pennsylvania Station, the majority were hauled away to a dump in the Meadowlands, not far from the tracks carrying the self-same trains the station served. As far as I know, only two original pieces are extant: two federal-style eagles that now gaze forlornly over the planter boxes over 7th Ave. One of those is highlighted in the following photo, as well as the Penn Station placard over the street entry.

Below is a closer shot of the station eagle.

Even the statue of Rea, as depicted at the top of this page, seems woebegone, really. It's not anywhere where most people are going to pay any attention to it. Instead, it's tucked up behind the canopy over the street entry, hidden from the street by bodegas and ATM kiosks.

When I first went to New Jersey to see where I would be working with The Shakespeare Theatre of - , I took Amtrak from Pittsburgh PA to New York NY , where I would pick up a New Jersey Transit train to Madison, where the theatre company was then headquartered. On the schedule Amtrak published, it noted that the train would arrive at New York Penn Station, and I thought "What?! That got torn down! Where the hell am I going?" That arrival in 2005 was my first of many experiences with Penn Station as it stands today.

Inside Penn Station as of June, 2013.

Does this qualify as irony? Displayed on a support pillar of the main waiting area is a photograph of Penn Station in its heyday. I wonder if anyone besides me ever looks at it.

When the station and its above ground structures were being "redeveloped" some of the original infrastructure was kept, albeit in conjunction with new equipment. To that has since been added newer still pieces as the world has gone more "wired," but the iron and brass still guide passengers to the boarding platforms, and Amtrak, NJ Transit and the LIRR still pass through much that was there in 1910.