Well, now we've come to it, I suppose -- nearly to the end of the road. While this is a chapter on the road trip, since it was one of the places that I felt duty-bound to visit, this chapter is also something of an epilogue. While I'm hardly a latter-day Dreiser, I'm going to follow his literary path a little more and allow myself to wax around the narrative of my run-out to see IU. If you've come this far, stay with me just a little longer while I take my time to wrap it up 'cause I'm not wrapping up so quickly.

To wit:

1915: The Great War is in its first full year, Christmas of '14 having come and gone and all hopes of the battles leading to a short and glorious conflict are completely dashed in the mud of "no-man's land."

: Orson Welles is born in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

: The North River Sub-aqueous Tunnels linking major rail road traffic from New Jersey to Manhattan are, in August of 1915, just a few months shy of 5 years old as Dreiser & Co head out. (more on the tunnels and Penn Station over here).

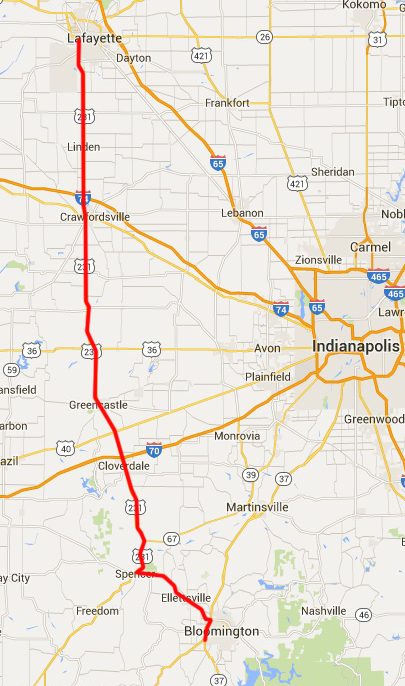

At left: West Lafayette to Bloomington, IN.

It's odd to work on this now after all these weeks of editing words and photographs, of looking for images from the past that might contribute to the over-all effect of the thing, of discovering some anecdote or bit of information that produced that "Oh ho!" moment, and then realize that -- after the last couple of years of consideration and driving and all -- it will soon be "done." Something like that ran through my head as I gassed up the saloon and turned South for Bloomington on a bright Friday afternoon in early August.

US 231 was recommended to me as a nice way to get there, and so I went.

Some little way North of Crawfordsville I passed this -- thing -- at a granary. Now, I figured it was a temporary silo structure, an inflatable model, if you will, which is all well and good in corn country. But having watched The X Files, (front to back, mind you -- hooray! for digital media) my first thought was "Oh !@#$! they're in Indiana now?!" as structures like this figured prominently in the movie Fight The Future. So of course I had to turn around, go back to take a photograph, and say "Scully -- Run!" before I got back on the road.

"In approaching [Bloomington] my mind was busy with another group of reminiscences. As I thought back over them now, it seemed to me that I must have been a most unsatisfactory youth to contemplate at this time, one who lacked nearly all of the firm, self-directive qualities which most youth of my age at that time were supposed to have."

Dreiser spent quite a bit of his composition relating "reminiscences" and observations that he had while motoring across the countryside, and why not? He had Franklin and Speed, and later Bert, to chat with, but his mind wandered a fair bit during the excursion, and the more-so while he was back in the Village writing. Having spent a fair amount of my drive with little other sound than that of the air blowing in the windows, I can relate: the mind has ample opportunity to wander from topic to topic. Thoughts of past years are interspersed with thoughts of what was just seen outside the speeding automobile.

I had an odd moment when I reached a particular intersection equipped with a stop light: where US 40 crossed my path I could see just where I had sat at the red light a few days prior, heading West for Terre Haute.

1915: Lassen Peak, in California, erupts. (It is the the largest volcanic explosion in the United States until the Mt St Helens eruption in 1980.)

: The USS Arizona is launched at the Brooklyn Navy Yard (commissioned in 1916).

Knowing that Dreiser & Co came into Bloomington from the South, I passed a little way around the town first, so that I could make my own way in such wise. That I was back on IN 37, where I had fetched up with the road construction the week before, I had, too, the odd moment of reservation for my own plan, but this day it was easily enough done. I turned left onto Fullerton Pike -- and immediately ran into Orange Cones! Damn! The intersection with Rockport Road was under re-construction, and for a few seconds I wondered if I might have to turn back, but no one and nothing directed me otherwise. I turned left onto Rockport and went in, then passed over to Walnut Street.

A little strange you say? Yes, but I had not the least idea what to look for or where I was headed, so I just went. Reaching Walnut I thought "I should go South a bit more." Later, I would see that I could have gone so far South that I could have made my turn on to Walnut from IN 37, but -- oh well!

After some distance I adjudged my position to be sufficiently removed to turn around. As I rolled back toward the town, I imagined that the sights had likely changed since the Pathfinder went through here.

Below left: the view along Walnut Street, North-bound. At right: "What Would Theo Think?" At what point does one's suburban demesne become a burden on one's time, even with modern conveniences like a "riding mower?"

I mean, "IDK," 'cause like, Dreiser had this estate in Upstate New York - Iroki - which he expanded from a farm house and fields to include several buildings and landscaping, but, y'know, he was paying someone to do the construction and whatnot. For all his egalitarian thoughts and efforts, he still preferred to leave much of the drudgery of labor to others. But, y'know, he was a writer. If left to his own devices, I imagine that he would probably prefer something less than a lawn that he would have to mow at regular intervals, just to have, well, a lawn. But anyway --

"As a whole, the town was greatly changed, but not enough to make it utterly different. One could still see the old town in the new." Of course as the Pathfinder rolled into town, the skirts were probably no so far out as today -- but I could say that of any town, I imagine. Remember New Milford way back in Pennsylvania? Bloomington has crept out beyond its earlier lines, putting down fresh pavement, new food joints, larger gas stations. Again, looking over at the Marathon, I thought that Bert or Speed would take it in silently, but rejoice in their silence for the ease with which an auto can be fueled.

Eventually, I found more of the old town, and Walnut quite to my surprise became one side of the town square. Probably because of the proximity to the IU campus the Bloomington square is a location I can easily imagine "jumpin' " when classes are in session.

"...the old, ramshackle, picturesque attractive court house had been substituted by a much larger an more imposing building of red brick and white stone -- a not uninteresting design -- still a number of the buildings which had formerly surrounded it were here."

Quite in contrast to my impression of downtown Evansville, there was that "something" to the mixture of old and new buildings, and their contemporary occupancy, around the square that impressed me, even though it was not terribly busy this day. It just had that indefinable air of use. Not only utility, but of some real life having been lived there.

Following: scenes around the court house.

The businesses in the old and new buildings also spoke to the sort of customers expected: from many "walks of life" and even from different countries.

Yes, this was one of the places where I bothered to alight from the saloon and amble about on foot. It was another good day for it, and as had happened in Indianapolis, there was conveniently a place to park on the square that required no "hunting."

A block off the square are the Zeitlow Justice Center (at left) and the One City Centre Building (at right) which began life as a Masonic temple, and is now a general office building. Seeing the Zeitlow building reminded me that in Warsaw, across the street from the court house, was a city block filled with a justice or law enforcement building; now as then I had to ponder -- what is the impetus for them? Is it only the real or perceived need for "more space" for all the new stuff we use today? Or is there some, maybe unspoken, urge to put up an imposing show for The Law?

Of the things I've observed of government architecture: I don't, generally, care for it. Not the more recent examples anyway. Typically the interior, and sometimes the exterior as well, shows nothing so much as an utter lack of thought. According to the tenets of the Bauhaus, form should follow function, but in the world so far removed from the Bauhaus, so far beyond even the "post International" style, with "lowest bid" construction thrown in to boot, what usually happens is the least attractive of anything regardless of function. The form is formless, bland -- blank, uninspiring, uninspired. I've seen some spaces that appear as if whomever did the planning were actively disdainful of crafting anything remotely hospitable. The rooms where the public interact with the government employees seem particularly effective at being inhospitable, as if the overt idea was to make the public uncomfortable, even to make them feel "small" or unworthy of the action they are requesting of their government's agencies. There are some exceptions of course, but by and large, I have to imagine that working in government offices must have some depressing effect on the employees; it certainly would on me.

Having traipsed about the immediate area of the square, I drove about for a few minutes and found an antique store. Yay! antique store! Of course I went in, and found a nice summer hat for a whopping ten dollars. Following this was more roaming through the streets, during which I passed this old truck, now a billboard on wheels.

I was, after a fashion, looking for the IU campus, which I knew was around somewhere, but in my uncanny way I was not finding it.

1915: Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis is published.

: In mid-January of the year the Endurance, bearing Earnest Shackleton's expedition to the Antarctic, becomes trapped in the ice floes, and will remain so until late October when it is finally crushed and sunk. (The men will continue to live on the ice until the Spring of '16, when they make for Elephant Island in small boats.)

While I was beginning the work on these pages, I happened across a book that looked to be just about perfect: The Big Roads by Earl Swift, which promised right on the cover to be "The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways." Well, I'm pretty much a sucker for those "untold story of history" books and considering I had just done a journey over Americans road and highways, this seemed right up my proverbial alley. Indeed, it illuminated quite a story, much of which was new to me.

Some of the story I had read, or heard, before, like the coming of the bicycle and the cry for better roads.

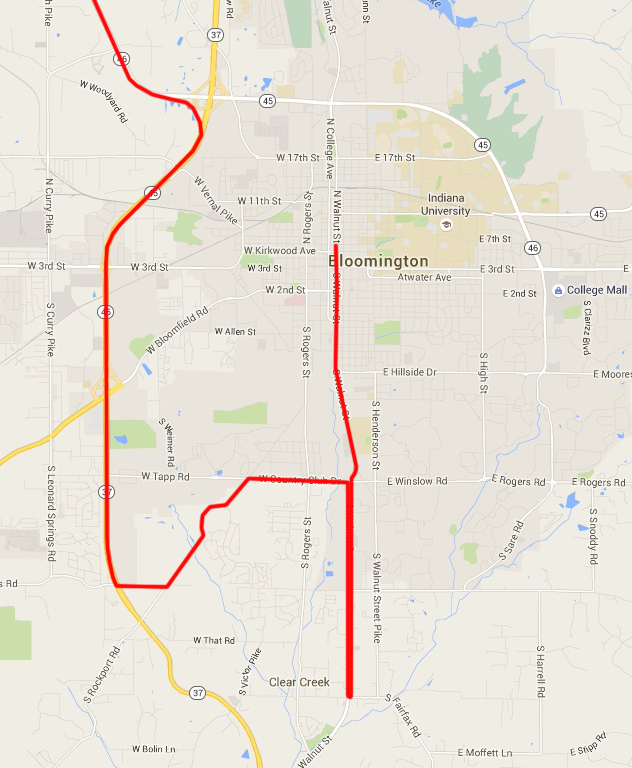

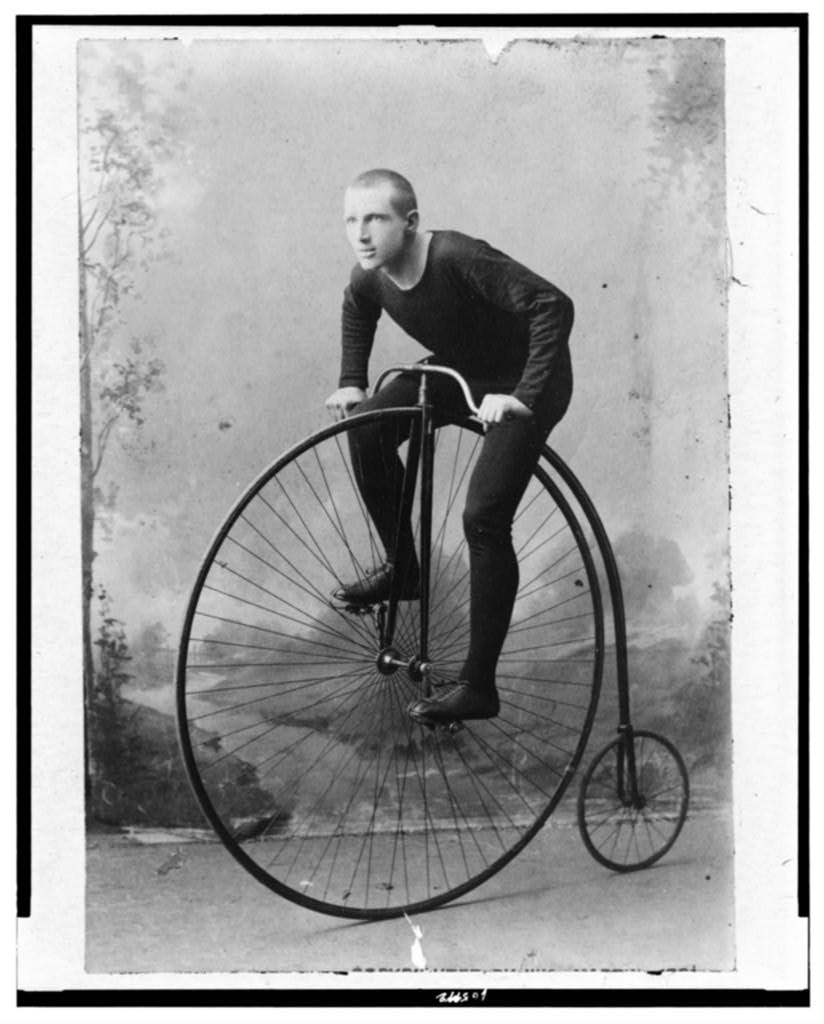

Above left: William Martin, cycling champion, photographed in 1891 astride his "bone shaker." At right: the "safety" styled bicycle of 1897, what we would recognize as a "bike" today (both LOC). "The Start," I'm sure, is in reference to the recommended procedure of getting astride a safety bicycle. It might be hard to make out in the photo, but the young woman has her left foot on the peddle here.

The "bone shaker" cycles, or "penny farthing" models, had iron wheels, no brakes, could not coast, and put the rider at some height off the road, which could lead to spectacular stops -- not uncommon on bad roads. The advent of the safety-style bike allowed for more people to indulge in the sport, and interest grew across the United States. Cycling clubs sprang up in many cities and towns, and as long as the weather was fair, or if those cities and towns had put in some kind of paving in their streets, cycling could be a great pastime, a way to get out and exorcise, get some fresh air (at least where there was fresh air to be had -- but that's yet another story), and meet your fellow Americans. But those roads and streets were not always so good. In most places they were bad -- really bad.

The cycling clubs, because they were often (maybe mostly) populated by the rising middle class and other well-to-do citizens, became what we would call today the "grass roots" in a years-long effort to make the roads actually worth riding over, to improve them to the point where the cyclists would not be stuck in the mud or thrown off their seats.

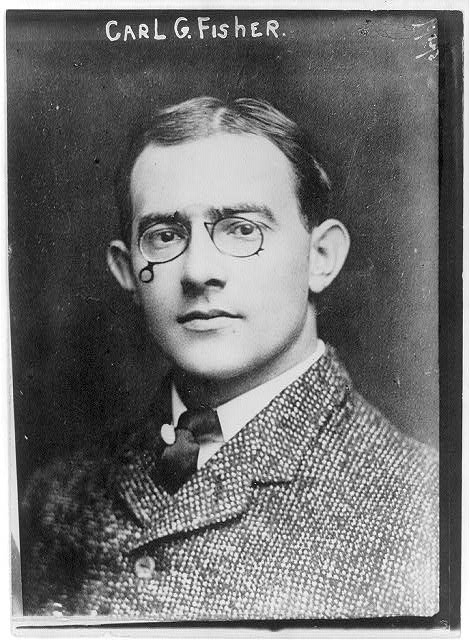

That's where Swift begins his story: with cycles and mud, and a Hoosier who was at the forefront of the battle for better roads -- Carl Graham Fisher (at left, in 1909 [LOC]).

Born in Greensburg, IN, Fisher moved to Indianapolis in his youth and would eventually become the archetypical self-made millionaire businessman. Taken with the bicycle and cycling, he had a cycle sales and repair shop in Indy that would become very lucrative. When he took up with the young automobile, he threw over the bike shop for a car dealership which would become even more lucrative.

He would go on, with some like-minded friends, to found the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, or "the Brickyard" for its paving, and bought some Florida coastline which would become Miami Beach. Yep, that Miami Beach.

Walking to school in West Virginia, 1921 (web).

"When Fisher was born...in 1874, the automobile's American debut was still two decades away. Overland travel was the province of the train. Look at any map of Indiana from the period...and you'll see tangles of thick black lines converging on the major cities; smaller settlements are reduced to dots on those lines...Most of the old maps don't depict a single road.

They were there, but hardly in the form we think of them. The routes out of most any town were 'wholly unclassable, almost impassable, scarcely jackassable,' as folks said then -- especially when spring and fall rains transformed the simple dirt tracks into a heavy muck, more glue than earth...people braved them to the train and back, or to roll their harvest from their farms to the nearest grain elevator. For any trip beyond that, they went by rail."

When Dreiser & Co visited the Haynes Automobile Company in Kokomo, they were visiting the premier automobile manufacturer of the United States. The Haynes-Apperson that made the round trip from Kokomo to New York was the one of the first of the many millions of "cars" to be produced in America, many of which would, in those early years, be built in Indiana.

At right, a 1901 Haynes-Apperson, described as "extremely rare," at the Auburn Museum in Auburn, Indiana.

It makes sense to me now that Booth would have purchased a Pathfinder, as it was an Indianapolis company.

Here, Ezra Meeker in 1916, prior to attempting his own re-creative road trip: a tracing of the Oregon Trail in a custom Conestoga-styled Pathfinder (WHBP).

Pathfinder positioned itself as a "high end" auto, in direct competition with Cadillac and European import models.

With the advent of the automobile, and certainly with the coming to market of what we would know as a "car," many of the people in the bicycle clubs became ardent "autoists", and clubs for drivers took off.

At left, the Hoosier Motor Club meeting at Monument Circle in downtown Indianapolis in 1908 (WHBP).

As the auto became more affordable, popular, and more reliable, the outcry for better roads shifted from the cyclists' demands to that of the automobile enthusiasts'.

"Outside the business district, roads dwindled to little more than wagon ruts...a sprinkling of rain could turn them to bogs; their mud lay deep and loose, could suck the boots off a farmer's feet...Some swallowed horses to their flanks; the unfortunate buggy that ventured down such...soon flailed past its axles in the ooze...American business was conducted in mud-soiled suits, as were law, medicine, and church services."

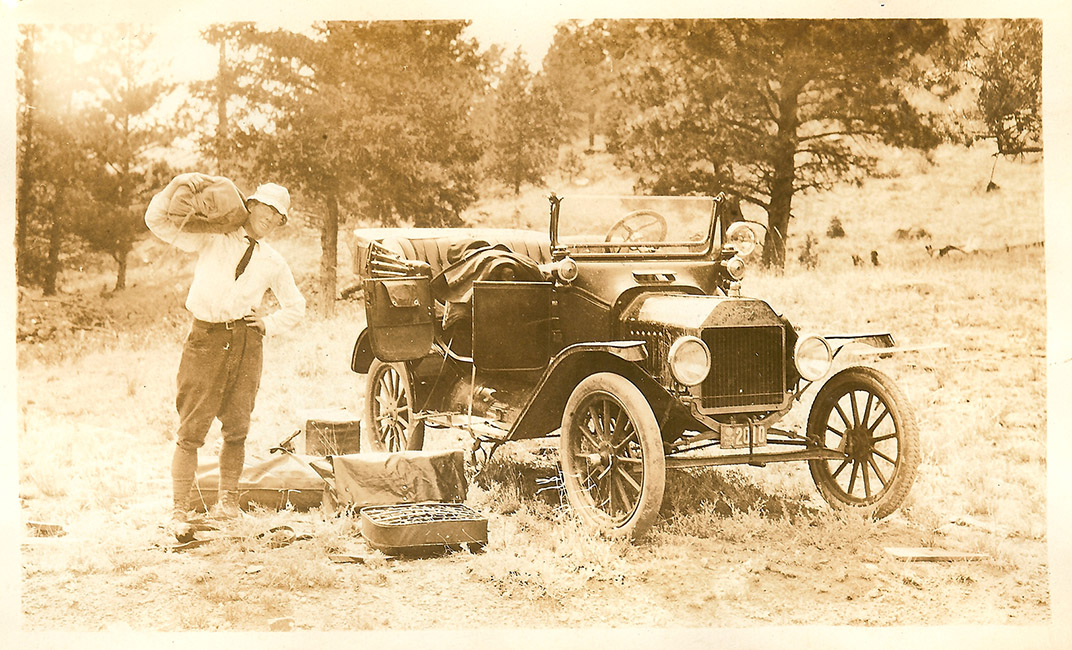

And let's face it, the automobile would do no better in the mud than a buggy. As can be seen below, at left:

Turns out that 1915 saw another cross-country road trip made by someone with a well-known name: Ford. In August of that year, Edsel Ford and some friends thought it would be fun to drive from Detroit to San Francisco to visit the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. What Edsel discovered was that the roads were crap, and the Model T didn't have a lot "under the hood." In the photo above (right) the car is being stripped of nearly everything so that the engine can "pull" the next hill.

I suppose it shouldn't be a surprise, but I did have a "What?!" moment when I came across this story: a group of Model T enthusiasts re-created that road trip in 2015, to commemorate the Century mark. Of course they did! And they had Model T's to do it in. Le sigh.

The auto, carrying its own motive power, was also seen as a viable alternative to the then-common means of non-human motive power, the horse; and all that a horse left behind it.

"...mixed with the mud was a liberal helping of manure...The situation was grim enough in small towns, where the population might number a few hundred humans and a few dozen animals...In New York City, but one estimate, horses left behind 2.5 millions pounds of manure and sixty thousand gallons of urine every day. That amounts to roughly four hundred thousand tons of manure a year -- enough to float three Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carriers and a half-dozen navy destroyers. Forget the smell and mess; imagine the flies."

Horses were also expensive. The buggy or wagon might be cheap compared to the auto, but the horse required a lot of up-keep and feed, so as the car -- or truck -- gained in reliability and was mass-produced, the horse was, well -- put out to pasture.

People who had long since been restricted to short-distances at slow speeds looked forward to taking themselves and their goods farther and faster. Businesses relegated to siting near or at least not too far away from canals or train lines looked forward to increasing their reach: more raw materials could be got more readily, and finished goods shipped deeper into the countryside faster than before. If only the roads were better!

The mud would have to go, of course, and a variety of surfaces were used. The macadam road was a layer-cake of crushed stone on top of a graded bed; when the stone was compressed, it stuck together enough on its own to allow for travel. If the top layer was coated or mixed with asphalt or coal tar, it became tarmac. And after numerous experiments, the right proportion of material was found to allow for a concrete mixture that could withstand the weather and heavy automotive traffic.

The country was still growing, and better cars and roads were going to be part of the growth: it was the American Way!

Carl Fisher was there with his fellows, who would argue loudly for these kinds of improvements, and even for the creation of a designation system that would allow drivers to easily navigate from coast-to-coast, or from North to South. The idea for an interstate highway system was espoused, and then developed, before the First World War even started: the Lincoln Highway Association was incorporated in June of 1913.

So, yes, while many thousands of miles had been driven across the country already when the Pathfinder was taken on the 42nd Street Ferry, I'm still calling the journey made by Dreiser and Booth the "original road trip." As I think I wrote somewhere, when Franklin suggested the idea of driving to Indiana, the notion of driving to Indiana from Manhattan was, by that summer of 1915, no longer an adventure with rope and supplies and muddy lanes, but the same kind of adventure that we would undertake toady if someone suggested a "ROAD TRIP!"

Dreiser even wrote "I assume that automobiling...is an old story to most people. Anybody can do it, apparently." It was becoming common, though most people then, as now, were likely to only go a few scant miles from home (most people only ever drive within something like a 3 or 5 mile radius from their address most of the time). Or they would go out for pleasure on a Sunday afternoon. Sundays, remember, were the only day that most people would take, or were given, off from their work. "Sunday driver!" indeed.

It's that combination of reliable roads, a reliable car, and the undertaking of a thousand miles through unfamiliar lands, that together create a sojourn that was unlike auto trips made before. It was "modern," "up-to-date," and I think done with as much thought as that given by generations of subsequent auto owners: "Hey, I'll take the car."

The automobile, and the "lure of the open road," had become part of the Great American Mythos.

5th Avenue near 42nd Street, New York, 1912 (Shorpy)

1915: The RMS Lusitania is sunk by torpedo off the coast of Ireland; 1,198 perish.

: The SS Eastland capsizes on the Chicago waterfront; 800 perish.

When visiting in 1915, Dreiser went in search of the rooming houses and rooms he had lived in during his year at the university. The rooming houses, like the houses his where family had lived in Warsaw, were of an older age, and of one of them he discovered that it had been moved and a porch added. The family that lived there still took in boarders. He also wrote of an exchange with some boys playing marbles.

" 'Willie,' I said to a boy who was playing marbles with two other boys, right in front of us. 'how long has this second house been here -- this one next to the corner?'

'I don't know. I've only been here since Booster Day.'

'Booster Day?' I queried, suddenly and entirely diverted by this curious comment. 'What in the world is Booster Day?'

'Booster Day!' He stared incredulously, as though he had not quite heard. 'Aw, gwann, you know what Booster Day is.'

'I give you my solemn word,' I replied, very seriously. 'I don't. I never heard of it before...'

'Where dya live then?' he asked.

'New York,' I replied.

'City?'

'Yes.'

'Didya came out here in that car?'

'Yes.'

'And they ain't got a Booster Day in New York?'...

'Well, what do they do on Booster Day?' I inquired...

'Well...they, now, send up balloons and shoot off firecrackers and have a parade, and someone goes up in a flying machine, at least he did last year.'

'Yes, what for though?' I inquired.

'Because it's Booster Day,' he insisted."

As I read that passage (they did eventually get back 'round to the subject of the house in the original question) I was reminded of the Sinclair Lewis novel Babbitt, with its tale of the boosters, the businessmen, the people who spoke oh-so knowingly of things they only knew of through other boosters' pamphlets. The way that "Booster Day" was seen by a boy playing marbles. At a guess, "Booster Day" was just that: a contrived holiday to get people to come see things -- like "flying machines" -- and drum up business for Bloomington. "Look at how up-to-date things are here in our splendid city! You want to come spend time and money with us, not the other guy!"

Just for curiosity's sake, I did a "search" for "Booster Day" on-line, and found an entry that described a young pilot crashing his bi-plane in 1911. Of the larger holiday there is but little, though if I read the story aright, 1911 saw the inauguration of the event, and a large number of people came into Bloomington from smaller surrounding communities, some riding on a special train run by the Monon Rail Road. Appropriately enough, there was a Booster Club committee that was part of the Commercial Club. All of which adds to my idea that "Booster Day" was just what its name implies.

Of course today, the students don't have to settle for rooms in houses occupied by other families. Oh, no, student housing is a big business in its own right. While I was driving about I came across a few examples of this.

"Lofts?" Now it appears that "lofts" can be anything someone decides they are (above, left). They used to be drafty industrial spaces occupied by artists looking for cheap rent. Now they're being built by developers? So even the term "loft" has been subjected to gentrification, I guess (above left). The sign in the lobby window (above, at right; not the same building, no) lists "free unlimited tanning" and an "awesome game room" among other things to lure tenants.

The streets in the vicinity of those apartment buildings are equally subject to modern development, here with a parking garage with bar and grill at street level. Plus the Taco Bell, of course, because students!

I wonder if it's open 24 hours?

1915: D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation premiers, and is screened privately at the White House for President Wilson.

: The Panama Canal sees one year of operation as of August 15th.

When I finally turned in past the sign for the university, the first thing I saw was the stadium. Yes, yes, I'm well aware the place that SPORTS! hold in the hearts of True Americans, but I still marvel at stadia like these. Marvel and shake my head.

The architecture of the stadium echoes that of the campus generally, or certainly the newer ones. "Muscular" comes to mind. "Heroic" maybe. This is the antithesis of the lowest bid government construct; these are structures that make it plain that they are here to stay, and have a very definite purpose. At least that's the way they appear. I'm sure they were probably built on some bid or other, but someone made some certain decisions concerning their appearance.

The older buildings, too, reflect what might be called the high academic. When you walk about buildings like these, there is no mistaking that you are on a university campus.

"After this came the university, wholly changed, but far more attractive than it had been in my day -- a really beautiful school. I could find only a few things -- Wylie Hall, the brook, a portion of some building which had formerly been our library. It had been so added to that it was scarcely recognizable. I ran back in the memory to all those whom I had known here -- the young men, the women, the professors. Where were they all? Suddenly I felt dreadfully lonely, as though I had been shipwrecked on a desert island. Not a soul did I know any more of all those who had been here...What is life that it can thus obliterate itself, I asked myself. If a whole realm of interests and emotions can thus definitely pass, what is anything?"

I drove aimlessly around campus for a bit, and was shocked -- no really, shocked -- to find that I had pulled to a stop and the building directly in front of me was Wylie Hall! "HA!" I said. I wasn't sure in the moment if it was the same Wylie, and the windows had obviously been changed, so -- ? It wasn't until later I realized I was looking at the back of the building, as well.

It is the same Wylie Hall, at least on the exterior. When Dreiser attended, it was a two story building with a tower and spire, but a fire in 1900 necessitated a reconstruction. A third floor was added, and the tower and spire left off.

At left, Wylie Hall as it appeared in 1904 (WHBP).

Since Dreiser had gone looking for the old houses he had lived in, I kept an eye out for old houses, too. As with Warsaw, and so many other towns I'd been through, the houses Dreiser would have recognized were old when he was there. Those are now gone, replaced by what are today old houses, but I imagine that many are still given over to student housing.

Here the houses are accompanied by my old companions, the Orange Cones.

These houses are fairly representative of the stock in many of the neighborhoods I drove through.

Below (left), the one house I saw that "might be old enough," and across the street (at right) some new something-or-other standing in stark contrast.

These I went by on the way back to the bypass, and shortly I was back on the road North. With a stop for gas and coffee.

As noted, driving for hours on the road does leave plenty of time to ruminate on topics large and small. Probably prompted by a story I heard on the radio, one of those topics ruminated on included the whole electronic media thing: the proliferation of devices like the "i-" anything, pocket computers masquerading as 'phones, and the programs and "apps" that run over all those microchips. The subject has been fodder for quite a few tests, studies, and observations over the last few years, all of which has led us to knowing not much more than before. We get generalizations like "information is not knowledge," and segments of the population being called "digital natives;" we get the rise of the "internet troll," and find out that children still follow in their parents' footsteps whether either generation wants to acknowledge it -- so if you're looking at your e-mail over dinner, your kids will do exactly the same.

One of the things that occurred to me was to take "what are our e-devices doing to us" and turn it sideways: we're not doing anything with our devices that we don't want to do. The desire was always there. Steve Jobs didn't invent the demand or the market for the "iPod," he just happened to be the guy whose company got there first. The Sony Walkman showed plainly enough that people wanted to take their private world out into the public, as did the portable "boom boxes" before that. People who walk around with "ear buds" stuck in their heads aren't doing it because anyone told them to. Yes, anthropologists may refer to homo sapiens as a race that socializes and builds societies, but humans also seem apt to isolate themselves in their own little worlds given the opportunity. And we certainly have ample opportunity to do so today.

The Pennsylvania Turnpike, East-bound, 2015. Plenty of time to think!

It may be a stretch, but it's not unlike the advent of the mass-marketed automobile. There were plenty of people who saw the car as, if not outright demonic, at least a problem that no one would really want to bother with. The majority of our citizens thought otherwise. Given the chance, most people bought cars. It was the thing to do! It was American! It was a way to individuate one's self from society -- get out on the road and go somewhere! And the consequences soon revealed themselves as roads got backed up in traffic jams, the parks got over-crowded with day-tripping drivers and their families, and everyone complained about the exhaust and the noise. But did that stop anyone from buying the next model? It might have stopped a few people, but many many more kept right on going back to the dealership, or to the classified section.

Sure the advertisers had their day, too, but again even the best advertising won't force anyone to actually make a purchase. The potential customer converts him or herself to an actual customer when they decide, "Yeah, I want one of those." Somewhere the desire already exists, or the all the advertising in the world won't make a difference.

(web)

Things I think about when I'm not staring at the glowing screen.

So, with the nose of the saloon pointed once again North, I again had a moment of "Well, I guess that's it!" I had seen Bloomington, even found a hall on the IU campus that Dreiser wrote about. Now what? As the sun cast ever longer shadows across US 231, I knew that I had several weeks of work to put this site together, but that was as much of a limited duration as anything. There are only so many photographs that would actually suit, and the accompanying narrative would have to be written and edited, and and and ---

And -- the traffic backed up. Actually, came to a complete halt.

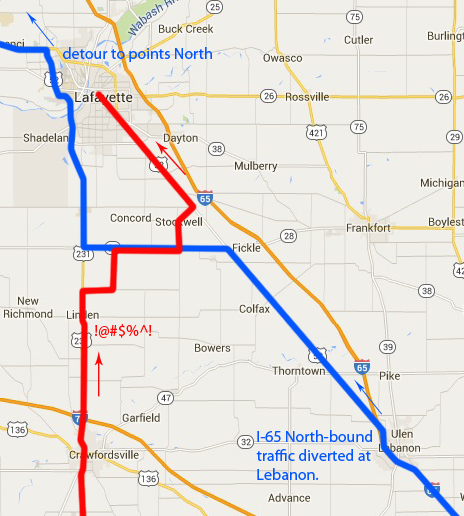

While I had been roaming about Bloomington, the state highway inspectors had been back to the I-65 bridge that had been closed earlier in the Summer -- and they closed it again. Traffic was once more shunted of of the Northbound Interstate to US 52, to Indiana 28, and to US 231, to circumvent the problem. A couple miles North of where the above photograph was snapped is the junction of IN 28 and US 231, where the Interstate traffic was merging with the local. Oy vey!

The detour is indicated in blue, at right, with my travel route in red. The approximate location of the photograph is noted with the censored exclamation.

I figured that since I was pretty close to Lafayette at this point, and had been over many of the county roads there-abouts, I would take my chances on "bailing" off the US or Indiana designated highways. The idea of being so close to home and sitting in traffic, literally sitting, just galled. So off I went. Did it take less time? I can't say, but it was a lot less aggravating!

Below left: looking South on US 231. At right: IN 28 with the detoured interstate traffic.

As for Theodore Dreiser, I won't say I know him, but I might understand him some. From Lingeman's biography, from the novels of his that I have read, it seems as though he and I arrived at some similarity of mind. Granted, that's not really a lot to go on, how-ever auto-biographical his novels, how-ever well researched another man's consideration of a life; but from our rather different circumstances, I recognize much of what has been illuminated. So much so, indeed, that it has been at times painful to read the descriptions of either Theo himself, or what Theo wrote of his characters.

Certainly I have to say that his observations from his journey across the nation are in the main close to my own sort of rumination. Not all, no -- I don't share his detestation of England, for instance, which his was based on his observation of the poverty of its working poor as compared to the luxury of the upper classes - and their lack of doing anything to remedy the problem. But then I do my best to refrain from spending too much of my self on detestation of anything; it's just too tiring, and I'd rather "spend the energy" on other things.

Though, again, I understand it.

1915: Einstein formulates his general theory of relativity.

: The modern Ku Klux Klan is established at Stone Mountain, GA.

At the time I sat down to start working on this last chapter, Paris, France, came under coordinated attack by gunmen and "suicide bombers" whose actions were claimed by the self-proclaimed 'Islamic State." Well over an hundred people, average everyday citizens, were killed, and many sent to hospital in critical condition.

Something like half the population of Syria has left their country to escape conflict.

Boko Haram, a radical militant group in central Africa, is still wreaking havoc, but the World isn't paying much attention to them, even though they managed to kill more people last year than ISIS.

Such is our lot in 2015. Need it remain thus?

The viral "Peace for Paris" image; original sketch by Jean Jullien.

It is, indeed, a strange thing to look at this (thoughtful pause here) endeavor and think "Well, that's it!" The journey and its recounting are nearly at their end. There are many things that I have started to write for this wrapping up, but they seem only to distract, or to veer away. Somewhere, some time, I will find a place for those words, but they don't quite belong here, so I will retreat to my place behind the camera, and allow Mr. Dreiser the last (or nearly) words:

"On my long, meditative ride back to New York, I had time to think over the details of my trip and the nature of our land and the things I had seen and what I really thought of them. I concluded that my native state and my country are as yet children, politically, and socially...They have all the health, wealth, strength, enthusiasm for life that is necessary, but their problems are all before them. We are indeed a free people, in part, bound only by our illusions, but we are a heavily though sweetly illusioned people nevertheless. A little over a hundred years ago we began with great dreams, most wondrous dreams, really -- impossible ideals, and we are still dreaming them.

The World Trade Center Memorial, South Tower Pool, Manhattan, 2015.

'Man,' says our national constitution, 'is endowed by his creator with certain inalienable rights.' But is he? Are we born free? Equal? I cannot see it. Some of us may achieve freedom, equality -- but that is not a right, certainly not an inalienable right. It is a stroke, almost, of unparalleled fortune. But it is such a beautiful dream...

There are dark places, but there are splendid points of light, too. One is [the American's] innocence, complete and enduring; another is their faith in ideals and the Republic. A third is their optimism or buoyancy of soul, their courage to get up in the morning and go up and down the world, whistling and singing.

On the North, or Hudson, River, 2015.

...I would have this tremendous, bubbling Republic live on, as a protest perhaps against the apparently too unbreakable rule that democracy, equality, or the illusion of it, is destined to end in disaster. It cannot survive ultimately, I think. In the vast, universal sea of motion, where change and decay are laws, and individual power is almost always uppermost, it must go under -- but until then --

Broadway and 42nd Street, Manhattan, 2014.

And so, were I one of sufficient import to be able to speak to my native land, the galaxy of states of which it is composed, I would say: Dream on. Believe. Perhaps it is unwise, foolish, childlike, but dream anyhow. Disillusionment is destined to appear. You may vanish as have other great dreams, but even so, what a glorious, an imperishable memory!

Walkin' the dog, 5th Street, downtown Lafayette, 2015.

'Once,' will say those historians of far distant nations of times yet unborn, perchance, 'once there was a great republic. And its domain lay between a sea and sea -- a great continent. In its youth and strength it dared assert that all men were free and equal, endowed with certain inalienable rights. Then came the black storms of life -- individual passions, and envies, treason, stratagems, spoils. The very gods, seeing it young, dreamful, of great cheer, were filled with envy. They smote and it fell. But oh, the wondrous memory or it! For in those days men were free, because they imagined they were free --- '

1915: Ford produces its one millionth car.

: Billie Holiday is born in Philadelphia.

Taking photographs in Indiana, on a blustery day worthy of Winnie the Pooh, 'cause even when it gets cooler, I still roam about and look for a scene I like:

Of dreams and the memory of them is life compounded."

So there you have it, dear reader. "Good night, and good luck."

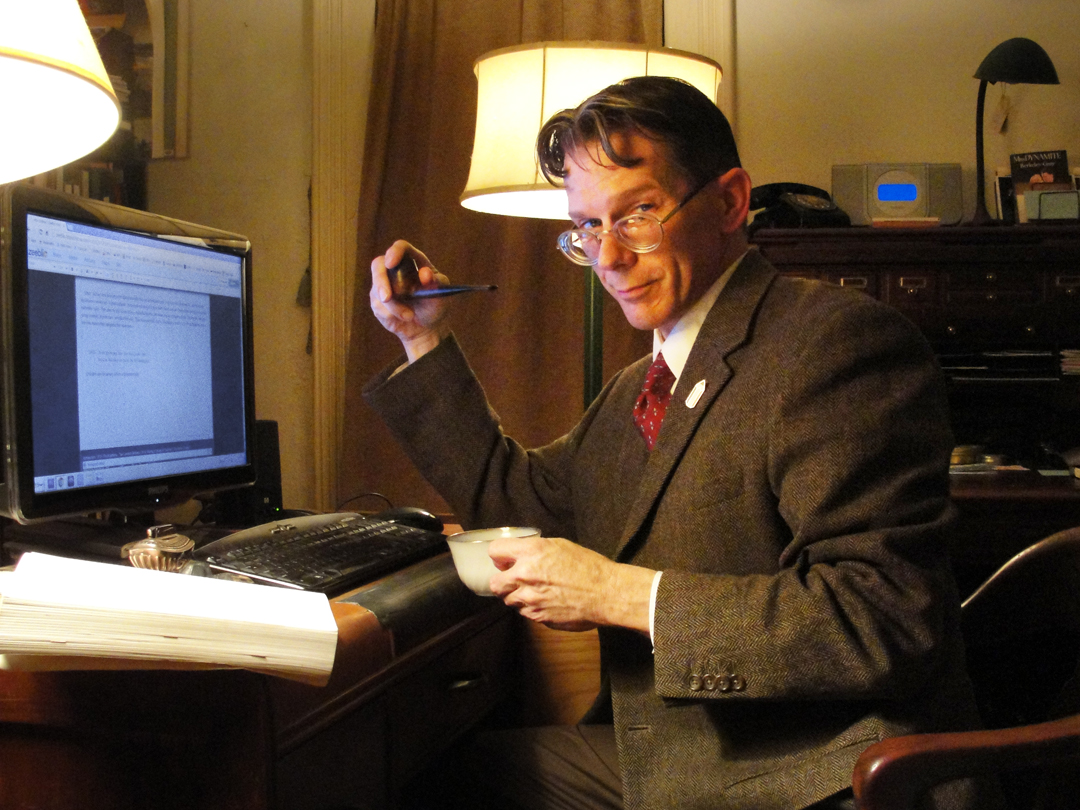

R. Jake Wood, November 22, 2015.