The impetus to create this stemmed from Purdue Galleries pulling a piece from its collection, Generator of Jobs, by American artist Rockwell Kent, and asking artists to craft a response to it. The results were displayed in the Gallery show On or About: Rockwell Kent in the Spring of 2016. The piece had been "out" a couple of years prior for a showing of items from the collection, and when I saw it then I thought "What is this? Why paint such a blatant piece of pro-coal propaganda?" But as one piece among many, that question wasn't being asked in any more than a rhetorical fashion.

Galleries Director Craig Martin had the bright idea to ask the question, and the show displayed over a dozen results. As I entered the gallery, turned the corner and saw the painting on the wall again, I almost immediately had a response of my own. It just took a little time to create it (more on that later), but finally I did, as shown above.

Below: the show card featuring the Kent's painting (the colors aren't great here, but fair considering the remove from the original).

Rockwell Kent was pretty well known in the mid-20th Century, for drafting lithographs and book illustrations and for landscape oils:

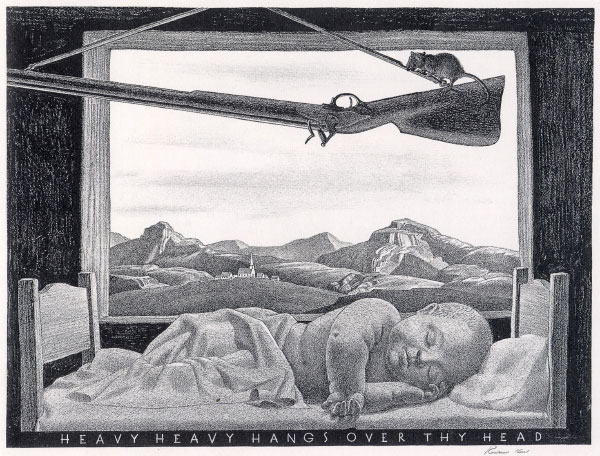

Above: left Heavy Heavy Hangs Over Thy Head (1946); right Abandoned Farm (circa 1950).

As director Martin related in a biographical sketch, "Kent [born 1882] painted as an American Social Realist well suited to New Deal propaganda, with figurative work of a symbolic and seemingly heroic nature...[he] was also recognized by many Americans for the countless illustrations he provided for advertisements in popular magazines and for printed book illustrations...He was also recognized as a prominent and outspoken advocate of workers' rights." His leftist political stance left him out in the cold during the McCarthy era, and the movement toward less realistic artistic expression in the post-World War Two decades left him out of vogue. As with many artists, he would regain some recognition only toward the end of his life; he died in 1971.

The question most anyone asks, then, is why did Kent accept a commission in 1945 by the Bituminous Coal Institute, "the public relations department of the National Coal Association." The job was to paint a series of images showing how coal improved America: better jobs, better economy, better living. How the coal operators treated their miners seemed to be ignored, though as a dyed-in-the-wool lefty, Kent would have known very well that the coal companies were among the worst of the Big Businesses. And yet, paint he did, though not to completion; what was to have been a 12 piece project was abandoned after 1946, a year in which a coal strike knocked the economy for a loop. In the Galleries' accompanying card is a quote from a paper by Dr. Eric Schreures of Mesa State College (Colorado):

"...it would appear as if he had ended up on the wrong side of the picket line, a position that would have most likely cause[d] him great displeasure...his art and reputation had been used...to promote management, rather than labor."

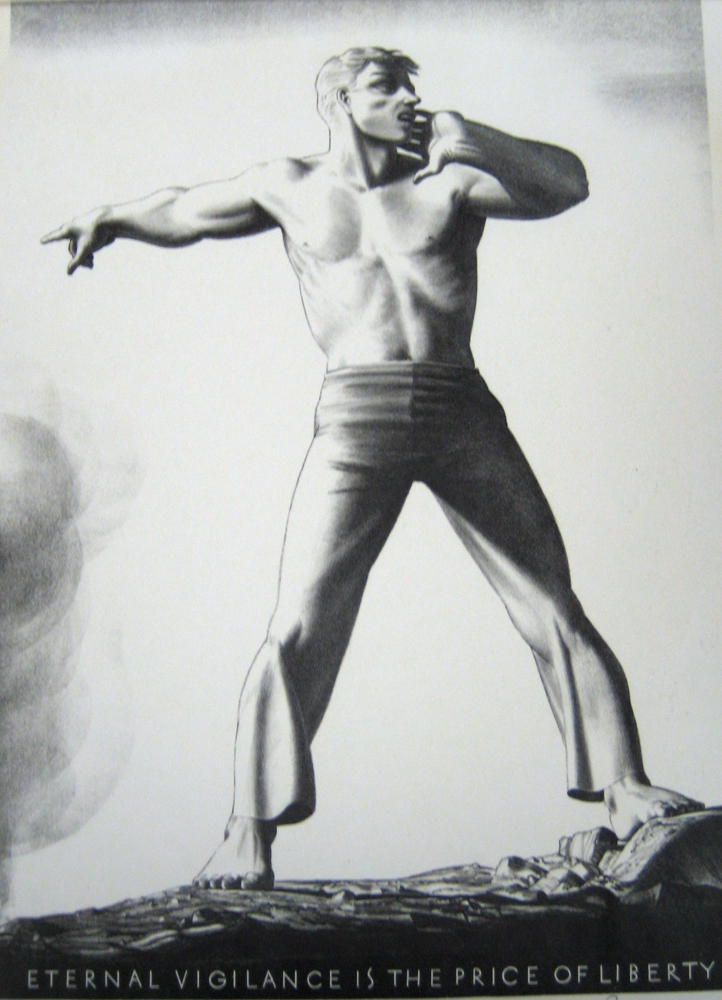

Rockwell Kent: below left America Land Of Our Fathers (circa 1950); and right Eternal Vigilance is the Price of Liberty (1945).

Just as quizzical as Kent painting for "the management" is how Purdue Galleries came to possess the painting. After the incomplete series was used in magazine adverts and hung on the walls of the Bituminous Institute's offices, Generator of Jobs was donated to Purdue University in 1947, one of several universities with mining in its curriculum. But in 1994 "...the Purdue Galleries staff got a phone call that a painting had been left by a dumpster and no one knew from where it had come or where it belonged." The staff retrieved it, cleaned it, and added Generator to the collection.

My first impulse to craft a response to Generator was to depict something that included a view of one of the "mountain-top removal mines" in West Virginia, but I didn't think my chances of getting a decent photograph of such were too good (time, distance, cost, security, et cetera). BUT - here comes the intersection: I knew from reading Dreiser's A Hoosier Holiday that coal was mined in Indiana, down around Terre Haute and points South. Dreiser related that as his trip neared and passed through Sullivan and other small towns on the road to Evansville that he remembered the mining from his childhood days in the 1800's, and there were the miners still, trudging home after their days underground in 1915. Maybe there were coal mines much closer to home! And so it proved.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources maintains a web-page that maps mining permits, active and inactive. A bit of noodling around and double-checking Google Maps pointed toward a few possibilities, which I pursued on a couple weekend afternoons. Hopping into my trusty saloon with camera, coffee and snacks at hand I went South to see what I might see.

My first trip found me in the middle of the reclaimed territory of the defunct Chinook Mine; some of it is declared off-limits and in one location there is still some equipment standing idle and rusting, but much is left open to whom-ever drives through; it is strange to stand in the midst of.

Above: reclaimed land in the Chinook Mine area, just South-East of Terre Haute, IN.

When a child in the Greater Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, my mother and I would sometimes drive out to an old neighborhood under the flight paths of the LA International Airport to watch the 747s go roaring overhead. The airport authority had purchased the land and cleared out the houses, light and power poles, and pretty much anything else - excepting the streets, sidewalks and foundations. There were steps leading to no-where everywhere you looked. It was just a bit odd, seeing that something had been there, but was no longer. The reclaimed land here in Indiana is like that: a bit odd. There are no houses, no power lines, and few structures. It is strangely peaceful, as grasses, trees, wetlands and wildlife had been restored - yet it feels off. I can't explain it any better. For all the picturesqueness of the vista, something is - just off about it all. Going out on a metaphysical limb it feels like the land is still wounded despite the greenery covering it. And the interstate is audible, only a couple of miles away.

The next trip out brought better results. Venturing further South, I at first encountered the Hillenbrand Wildlife Area - fairly vast tracts of reclaimed mine lands, some of which have gone quite arboreal. Other swaths are grass-lands and copses, some of which surround what I have to assume were the deepest of the mine pits and are now ponds - stocked for fishing:

In the Hillenbrand Wildlife Area, East of Sullivan, IN.

A few more miles on brought me to the real thing: the Bear Run Mine, South-East of Sullivan still actively extracting coal from the Indiana seams. It's a little difficult to discern here, but that dark splotch in the middle of the landscape is one part of the pit, going how far down I can't say, but easily more than a hundred feet, maybe much more. The gigantic trucks that run out of there look like toys in comparison to their environ (one is in the finished artwork, to the left hand side - yeah, look - it's not very big in the image).

In the distance can be seen some of the processing structures. That is actually quite a distance - those towers are really tall.

Really tall. I mean, like, huge, man.

While roaming through the Chinook area, I happened across an old cemetery, long since gone unused. Similarly, Bear Run surrounds this, the Pirtle Cemetery - and I do mean surrounds. Mine land totally encompasses this little plot of trees and graves. It hasn't seen a new head stone in nearly a Century, but someone in the last few years left a little bouquet of red, white, and blue plastic flowers near one old stone. They now sit faded and covered in dust. I couldn't say when they were left; could have been last year, could have been ten or twenty years since.

After the delay in discovering a suitable place to photograph a mine, the Bear Run pit became the background for the image. I had imagined from the first depicting that strange spectre of the coal industry from Kent's painting - only walking away from what it's created, rather than beckoning the masses; the idea of Lady Columbia figuring in the image came later. It was one of those "Oh, hey!" ideas that suddenly "just made sense" as the question of "King" Coal still looms over our nation and its future, much as it did in its history. Including our old national figure also informed the framing and typography of the finished piece.

And that, I think, is the story.