"Rust Belt America:" a view from New York Highway 5, here also entitled the "Buffalo Skyway."

After the relatively short loop through Buffalo (to which I said "I'm in Buffalo?!) I managed to find the entry out of downtown on to the "Buffalo Skyway," where NY 5 is elevated above the old industrial sites along Buffalo's Erie lakefront running South. On the East side of the Skyway, some of the old-line buildings of the Industrial Era still stand (as pictured above) along the creeks and lagoons that curl off the Lake. To the West, some of those industrial "brownfields" have been reclaimed as the Outer Harbor recreation area.

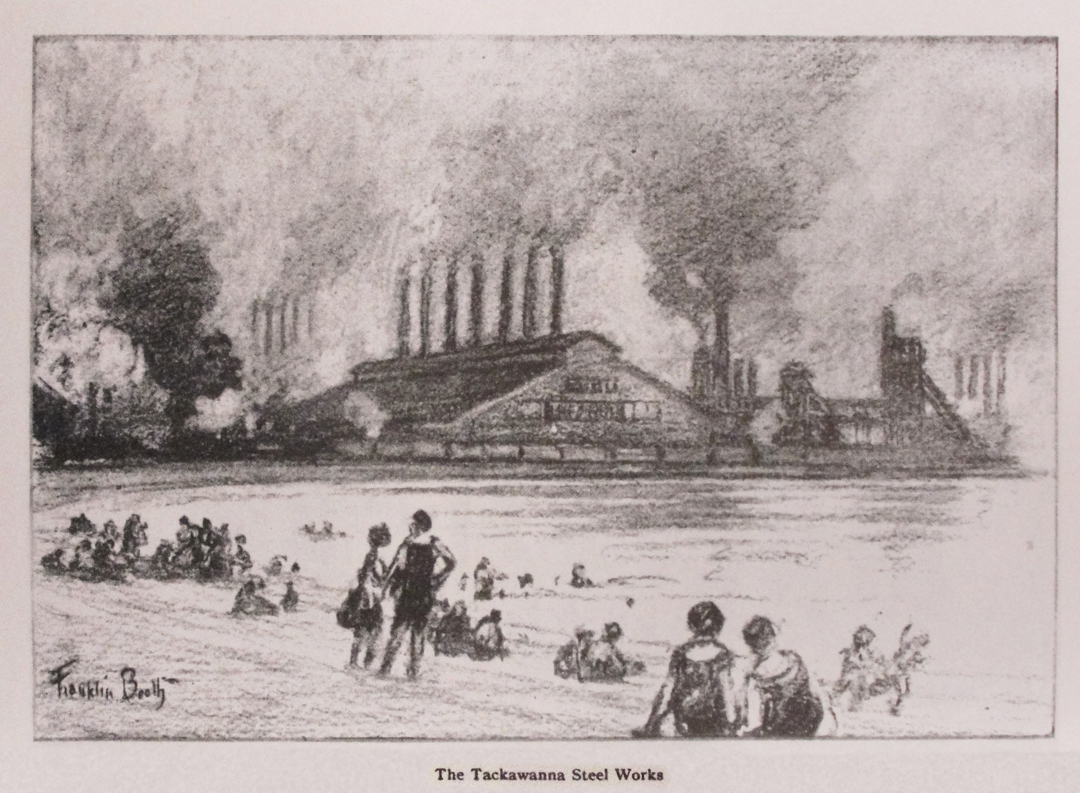

"Departing Buffalo, not stopping to revisit the Falls . . . we came to a grimy section of factories on a canal or pond, so black and rancidly stale that it interested us. Factory sections have this in common with other purely individual and utilitarian things, -- they can be interesting beyond any intention of those who plan them . . . The chimneys and roofs of these warehouses rose in such an unusual way . . . Franklin decided he should like to sketch them. So here we sat, he on the walking beam of a great shovel derrick lowered to near the

ground . . . "

"A few blocks farther on there came into view an enormous grain elevator, standing up like a huge Egyptian temple in a flat plain . . . Then came the lake shore, lit by a sinking and glorious afternoon sun, and a long stretch of that wonderful brick road, with enormous steel plants on either hand . . ." with accompanying drawing by Booth.

I doubt that this particular grain elevator is Dreiser's "Egyptian" temple, but when I saw it looming over the lake, his description immediately came to mind. The Outer Harbor area is curious: some of it has been replanted or restored to have grass and trees, bike lanes, and lake access, but studding through are these remnants of industry. As can be seen in the following two photos, the old and the new are "cheek by jowl:"

This one in particular strikes me as - I'm not sure of what. Ironic? Exemplary of monetary distribution of the 21st Century? The brownfield, growing green as Nature reasserts herself, old elevators of Industrial America, and power boats. That cove with the landing was to the South of the "Egyptian" grain elevator; to the North, the Outer Harbor was populated by people spending part of their long weekend in jogging, biking, kite flying, or just lazing on the lakeside - but these folk are not of the power boat class:

The view of the photo above is looking back along Erie toward Buffalo, while Booth's illustration below is facing the opposite direction, but the result shows that this section of lake frontage has long had similar use:

"Just outside Buffalo, on a spit of land between this wonderful brick road and the lake, we came to the Tackawanna Steel Company, it's scores of tall, black stacks belching clouds of smoke and its immense steel pillar supported sheds showing the fires of the forges below. The great war had evidently brought prosperity to this concern, as to others."

The Lackawanna lakeshore:

Are these industrial structures the remnants of the Tackawanna Steel Company? Probably. The massing of the structures on the lake side of NY 5 is not as dense any longer as it was when Booth did his sketch, but the grounds of this "industrial park" are pretty extensive, and have the hall marks of having been more built up once.

On the other side of NY 5 were more old mill buildings, looking much like the old steel sites that still dot some of Pittsburgh's brownfield areas, and possibly built in the bally-hoo years of the 1920's or in the war boom of the 1940's.

"Thousands of men were evidently working here, Sunday though it was, for the several gates were crowded by foreign types of women carrying baskets and buckets, and the road [was] crowded with grimy workers, mostly of fine physical build. I naturally thought of all the shells and machine guns and cannon they might be making, and somehow it brought the great war a little nearer."

Tooling on down 5, the industrial, or post-industrial, landscape faded pretty quickly as I left Buffalo, and soon I was sighting the lake through screens of trees and the architecture ran to mid-Century houses instead of hulking mills. NY 5 does a bit of twisting and turning through these little shore hamlets, and in one was this dog and burger "stand." It has the look of something that might have been a service station once upon a time - perhaps even when the Pathfinder passed! If it had been open, I might have gone in, at least for a soda. Maybe a dog.

There are three choices in traveling alongside Lake Erie in the part of New York: NY 5, U.S. 20, or I-90 - the New York State Thruway. I chose to stay on 5, as it kept close to the lake, dodging a little closer or a little farther away depending, I suppose, on whether there was a town to go through. In a few places, the casual visitors to Lake Erie had flattened the ground between road-bed and lake beach, and scratched a path down to the water. I stopped for this view of Eagle Bay:

I like to think that a view similar to this would have greeted Dreiser and Booth, and Speed, as they made their way West.

.jpg?1541257847516)

What surprised me at this informal turn-out was the landscape across NY 5: unlike so much of the rest of the country, here were acres gone undeveloped, or left to return to something more natural.

"About seven o'clock, or a little later, we reached the town of Fredonia . . . "

Somewhere along the lake drive, the Pathfinder left the pavement that is now NY 5, probably at Silver Lake. There, what is now U.S. 20 runs in common with Main Street, and that highway reaches Fredonia some 11 miles on. Without that particular reference, I stayed on NY 5, making my night's stop-over in Dunkirk, one of New York's earliest towns along the lake. The earliest settlement in the area was circa 1800, and as lake-based commerce grew, coupled with industrialization, Dunkirk as the settlement was renamed in 1818 after the French town Dunkerque, grew into a small powerhouse of a town.

Among other things, it was a lake boat stop between Detroit and Buffalo, was home to several boat building works, and to the Brooks Locomotive Works (later part of American Locomotive Company) which supplied engines to railroad companies for decades in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

I did my looping around the town to see some of the neighborhoods off of the highway, and if the grocery that I stopped in is any indication, Dunkirk and Fredonia still have a fair amount of life in them (it was a big, well-stocked store). There is still some lake commerce, and a couple of industrial parks, one of which - viewed by Google satellite anyway - was most likely the one time home to Brooks Locomotives. Niagra Mohawk Power built an electric plant on the lake shore in 1946, and it still stands as well (enlarged, I'm sure).

This photo shows the Ehler Building in the 1890's.

It was one of the extant buildings that caught my eye, and my lens, as I drove about the town.

Dunkirk, and Fredonia, probably retain their liveliness because of their geographic location: it's one of those population centers that an area has to have. The SUNY Fredonia campus probably helps, too.

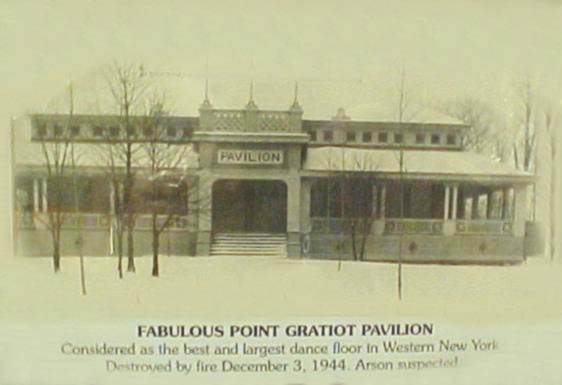

Part of the harbor complex, and part of life where water and land interact, Dunkirk's Point Gratiot has seen a lighthouse for most of the last 200 years.

The point now has a Dunkirk city park, and, along with nearby lakeside beaches, has been a place for recreation for the residents of Dunkirk since the late 1800's.

The current lighthouse structure was built in 1875 with a " . . . fitted with a $10,000 fresnel lens . . . " The lighthouse site is also home to the Veteran's Park Museum, with examples of militaria and U.S. Coast Guard memorabilia.

Yeah, I went because it's a lighthouse. "I'm on vacation!" being my regular thought, why not spend some time? While lighthouses do hold a small amount of historic fascination for me, I've not actually been in the vicinity of them all that often. The great Hatteras Light, of course, has seen me frame its image a number of times, as well as its Northern neighbor Bodie Island Light; and the light at Sandy Hook, NJ - but I think this is the only other one. I should find others, I suppose.

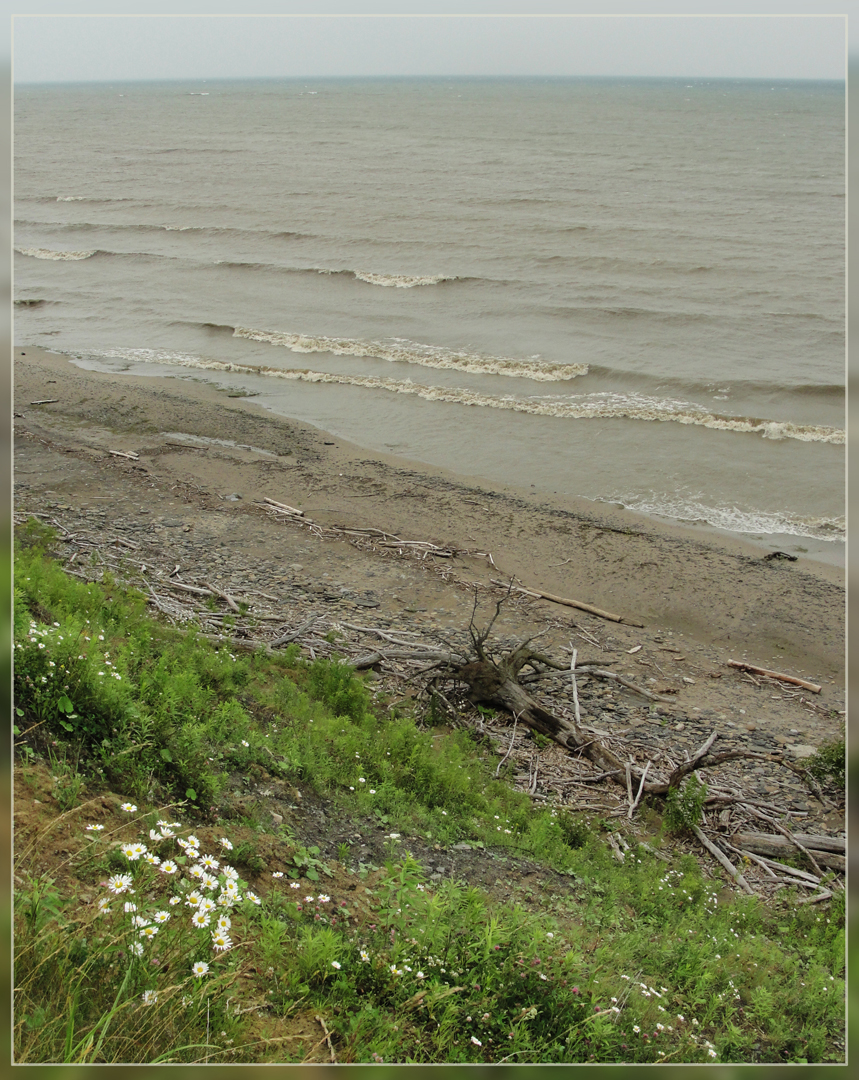

Lake Erie shoreline and Dunkirk Harbor entry from Point Gratiot Lighthouse site

The unassuming stream (below) emptying into Lake Erie is actually fairly important in the regional history: Canadaway Creek is reported to have been the landing site of the earliest English speakers who would go on to found the town of Dunkirk. Off-shore from Canadaway and West of Point Gratiot is where the first shot of the War of 1812 was fired.

At the time of taking this photo, I had no idea. There was the creek, running under NY 5, and just on the West side of the bridge was a turn-out for fishermen. So I stopped and went down to the water's edge. It's actually posted as a fishing creek.

20 or so miles from the state line, New York's Erie State Park offers camping, cabins, beach and woody hiking, and of course views of the lake. As it notable from the last few photos, July 7 2014 in Western New York was overcast and occasionally raining, but still afforded its photo ops.

About 7 miles from the state line I did one of my "turn-abouts:" I had passed another house that caught my eye, and figured "I'm on vacation!" so I might as well go back and take a photograph. I couldn't tell if the house was occupied; it had that look of being untenanted, the more-so upon closer inspection of this image: the window dressings show the raggedy ends typical of a haunted structure, or at least one where someone has stopped caring.

I found this house and intersection in a satellite view, and it looks like the real estate extends to the lake, some 1,200 feet back from the road. Between the views of the lake I passed the day before, as at Eagle Bay, and then seeing this house, I

think I want a "weekend home" on Erie.

Opposite the house is this view of farmland on the South side of NY 5. It's not quite visible in this photo, but the Thruway is maybe a quarter of a mile away: just to the right of the street sign in the middle distance can be seen the rise of this road to a bridge over the interstate.

Vineyards play a role in the local economy, grapes bound for jams and jellies - or at least I read that somewhere. Yes, I did snap the shutter at this scene with the thought that I could capture the image of avian passage; unfortunately the camera just isn't quite fast enough - but the blurry thing in the middle there is a bird, in fact.

How can you tell you've crossed the state line? The pavement changes! Welcome back to Pennsylvania.

"A town called Brocton was passed . . . On and on, through Westfield, Ripley, Northeast, Harbor Creek. It was growing late. At one of these towns we saw a most charming small hotel, snuggled in trees, with rocking chairs on a veranda in front and a light in the office which suggested a kind of expectancy of the stranger. It was after midnight now and I was so sleepy that the thought of a bed was like that of heaven to a good Christian."

Sometime in the wee small hours, Dreiser, Booth and Speed passed out of New York into Pennsylvania, intent on reaching Erie, though they had tried to gain a room at some unnamed "hamlet" before that city. Approaching Erie, they encountered a stretch of road that had been reduced to muddy ruts and holes:

" 'Erie Main Road Closed' . . . we recalled that there had been a great storm a few days or weeks before and that houses had been washed out by a freshet and a number of people had been killed. The road grew very bad. It was a dirt road, a kind of marshy, oily mucky looking thing . . . The car lurched so at times that I thought we might be thrown out. Speed was constantly stopping it and examining the nature of certain ruts and pools farther on . . . I began to think we were good for a night in the open."

That "freshet" turns out to have been one of the worst disasters to strike Erie: on August 3 of 1915, thunderstorms had dumped nearly an inch of rain per hour for six hours, causing detritus filled water to clog at a culvert in Mill Creek in Erie's downtown, flooding numerous city blocks. When the inadvertent dam finally blew out, the outrush to the lake swept away hundreds of houses and damaged hundreds of others. 36 people lost their lives.

Entering Erie, PA, in the daylight hours on PA 5, the town I saw showed the usual Rust Belt adaptation to the 21st Century: older housing stock making its accommodation to contemporary life in a city that may or not have reason to keep on going. Erie is still substantial of size, however, and not likely to disappear any time soon, though its fortunes might be a little shaky.

I remarked to someone that this road trip was a look at just those sorts of towns: the burgs, hamlets, and small cities that have been struggling to find their place, even after more than 30 years since "industry" dried up or left for Mexico and China. That so many do remain is testament to something - inertia perhaps, or stubbornness. I have a pet theory that part of what made the United States "go" from its earliest existence was that it was populated by the people who "left:" immigrants who, for what-ever reason, came away from their homes in Europe, or Asia, or Central America, to find something, if not better (the Lower East Side is better?) then at least the chance that something better could happen, if only for the next generation. This "left that for this" attitude, I think, made an huge impact on America's development - both in fact, and certainly in its mythos - that directly led to the opening of the continent, the development of its industry, the automobile and related industries, and so on.

But, curiously, the "recessive" traits also crossed the oceans: in towns all across the middle of America, whether Rust Belt like Buffalo, NY, and Youngstown, OH, or Lead Belt like Picher, OK: people just won't leave. They were born and reared in or near these places, and having set down their lives, they are unwilling to go anywhere else, no matter what has become of the municipality of their residence.

Some, of course, may also find themselves unable to leave because, if the economy of their town has fallen on hard times, their personal resources may not support a move to any other place. Too many people, as seen from our most recent economic recession - and even the years leading up to 2007-08 - find themselves out of work for any number of reasons, and unable to gain a new "situation" despite "pounding the sidewalk" or e-mailing hundreds, or even thousands, of resumes. In such straits, it would be next to impossible to "pick up stakes" for a pasture that may be, but might not be, "greener."

So Erie? Could be.

Two views of Erie, PA, along PA 5.

In Erie's center, the economic and migratory confluences exhibit themselves in shops and names that Dreiser would probably recognize, though he might have expected them in Lower Manhattan.

And certainly the three men in the Pathfinder would marvel at this epitome of the car culture: the interstate interchange. The archetype of automobile infrastructure, I suppose it is to the post WWII years as the major rail stations were prior to that. Except here, of course, it's people in their little personal boxes, instead of rubbing elbows crossing the waiting areas.

I wonder if that terminology helped pave the way for the demise of passenger rail travel: in a station, people "wait" for the train, and given the chance, a lot of people don't want to wait - not when they can get in the car and "go." The term for the thing, after all, is automobile: auto - self; one's own -- and mobile - able to move or be moved freely or easily. Move yourself around freely: the American dream, made manifest. Right?

And as this photo attests, it was back to the interstate for me following Erie. While the Pathfinder would continue along the Erie lakeshore into Ohio, visiting Ashtabula, and Cleveland before turning South-west into Indiana, I was bound back to Pittsburgh for a night before making my last leg back to Lafayette. On the way I stopped at one of our most American of institutions: the factory outlet mall to shop for a pair of shoes, and once in Pittsburgh I bought that most American of car accessories: a 12-volt USB plug mobile phone power converter. Oy vey.