Driving North along the East side of the Ohio River from Wheeling, I could hardly but notice how many structures there still were holding-over from the days when cities like Weirton, and Pittsburgh, and Bethlehem produced the vast quantities of iron and steel for America's industrialization. Some of the mills were still in use, though to what extent I can't say. Being tired after a day on the road, and not seeing any ready places to pull over, I passed through several small mill towns along West Virginia 2 without taking any photographs. After a night's sleep, however I said to myself, "Hey, I'm on vacation - I can go back to Weirton and take photographs!" Which is what I did.

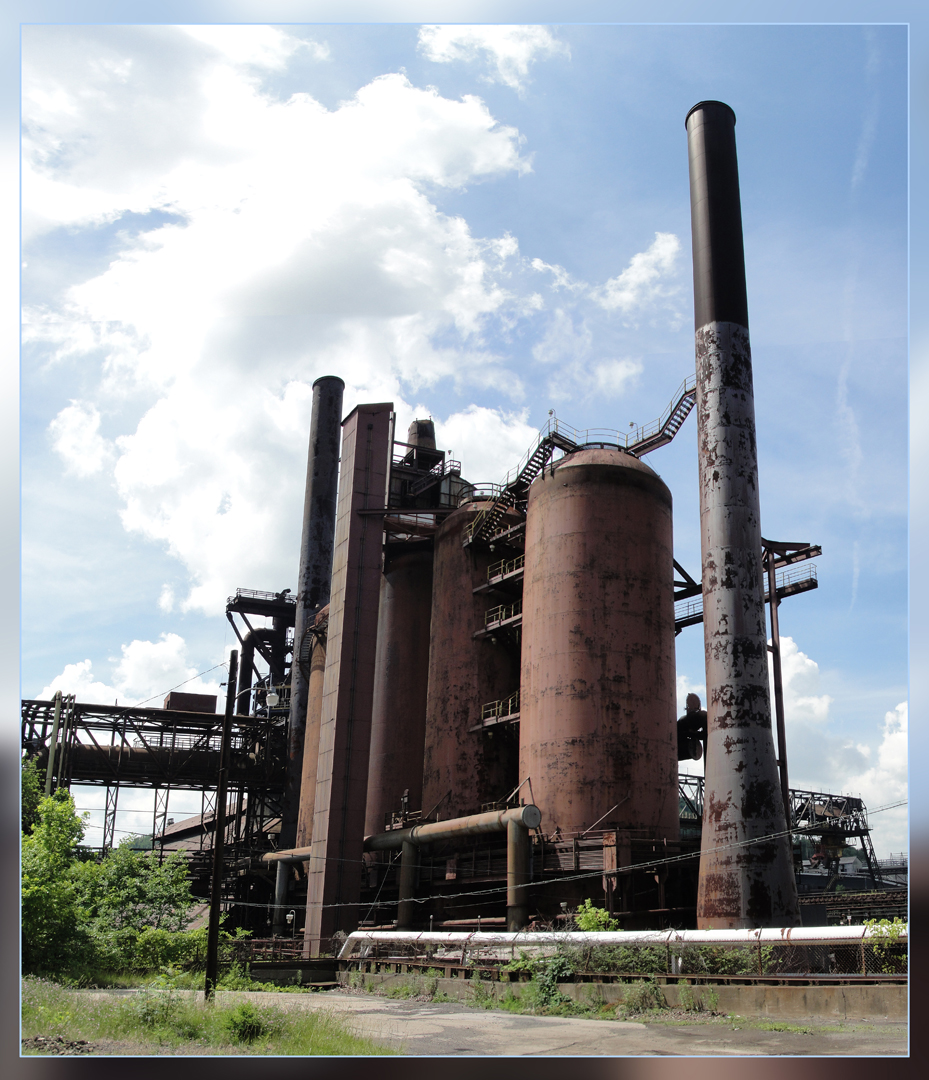

Mill view along 2nd Street below Ave "A"

Like many of the old-line steel towns in the industrial heartland, Weirton is now part of the "Rust Belt." Some of the machinery is still in use, but a lot of the mills are under utilized with the advent of cheaper imports made possible by mass cross-ocean shipping. These three views are in the Northern reach of the town, where Nature is making inroads in the absence of what had once been residential areas.

The corner of Ave "A" and 4th Street. Above: mill view Below: looking up Ave "A" toward WV Hwy 2

Not all of Weirton has the appearance of post-apocalyptic movie back-lot. There is still obviously some work in at least some portion of the mills, and people still live and work here. The views from the neighborhoods are still overshadowed by the mill buildings: the cars got newer, but the classic mill town is like this:

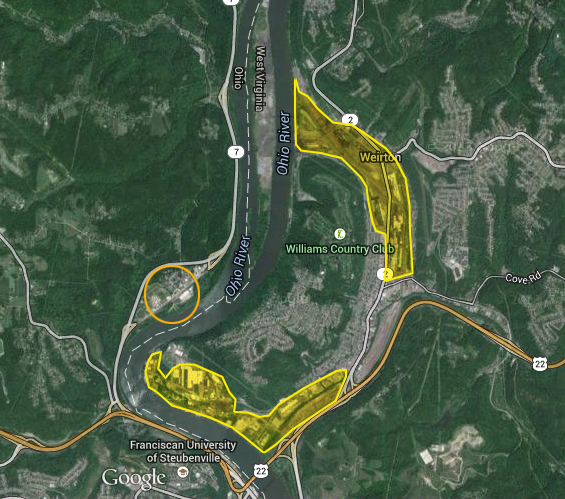

This Google Map view of Weirton shows what to my, admittedly amateur, eye is a town built in what had been Ohio River-bed at some point in the distant past. Highlighted are the industrial sites; the mills, operating at what-ever level, are mostly to the North end, while to the South, a commercial zone has been established, including an office/warehouse park along the river.

The residences clearly had been in between and around those mills - and as so often happens, people with more money would later mov to the top of the hill, or up the valley to the East to get away from the smoke (and the hoi-poloi, no doubt). That there is a country club in Weirton is just weird to me.

Across the Ohio River, on the Steubenville, OH side, was a building that just screamed "Take a picture of me!"

Seriously - "Barium and Chemicals, Inc." ? It sits in the "Pottery Addition," which in the Map above is in the orange circle.

(I have to smile, though: reading the word "barium" always reminds me of the line from Larry Shue's The Nerd that "barium crunch" had failed as an ice cream flavor.)

Down the Ohio from Steubenville on Ohio Hwy 7 was a town for which it looked like "Rust" was being replaced with "Dust." Mingo Junction had a steel mill at one time, but what I could see from outside a defunct high school building it appeared the the mill was actually being dismantled and bull-dozed over. The Main Street was lined with buildings that looked forlorn for want of tenants. At some point I'll swing back by this and see if, in fact, the mill remains yet, or has been knocked down.

BUT there's always bridges and trestles to lighten the photographer's day. Where road and rail traffic cross between Steubenville and Weirton stand great examples of the old and the new.

A railroad trestle, now crossed by Norfolk Southern, spans the Ohio River near the junction of Ohio 7 and U.S. 22. It's a fine example of the "the way they used to build things:"

By contrast is the road bridge carrying U.S. 22 across the river just up-stream: the Veteran's Memorial (Weirton-Steubenville) Bridge was in development/under construction for 30 years, opening in 1990. The West Virginia Department of Transportation has a nice overview of its history here, including how much concrete and length of cables and whatnot.

Then there's also the almost paradoxically contrary Pittsburgh, PA: granted that Pittsburgh is, and was, considerably larger than Weirton or Steubenville, or any number of other mill towns, but somehow it has managed to maintain an economy after the coming of the "Rust." Partly, I think, because the 'burgh is home to several institutions of higher learning - including Carnegie Melon University and the University of Pittsburgh - and also probably because there was simply more money here for longer. The Melons, the Fricks, the Carnegies, and their ilk - call them entrepreneurs or robber barons - people who had funds and put down amounts of it in banking and commerce in this city perhaps went further than they imagined in helping ensure that after the mills mostly went bust that Pittsburgh would find a way to continue.

Downtown Pittsburgh from the South-bound lanes on the Fort Duquesne Bridge, crossing the Allegheny River.

It's easy to see in both of these photos that architecture is layered in ways in Pittsburgh that I don't see much in other American cities. Manhattan, for instance, does have the old and the new in construction, but the constant re-building doesn't leave a lot of overlap. The 'burgh, though, has a little of all of it, and it has a "certain something" that I've thought of as a European hold-over: as if the mill working immigrants of the 19th Century are still exerting part of their heritage here. In the form of clustered frame and brick row houses clinging to the slopes, to the juxtapositions of generations of downtown offices getting ever taller and more glassy:

Now I've only ever seen Europe in photos and films, and I've read or heard some concerning the European view of infrastructure, but there is a strange quality to their over-lapping of the old and new that to my very American view is - well - alien. I suppose when your town is 600 or 800 or more years old, the old buildings are just that: old. Who gives a ______ ? It seems that Pittsburgh has an American "take" on that over-lap, and is maybe still an inadvertent hearkening to the 19th Century immigrant. And many of those "robber barons" could look over their shoulders to fairly recent immigration themselves, so perhaps it's fitting.

Speaking of Europe, there was, once upon a time, a grand vision for the University of Pittsburgh campus: it was planned to be an American version of England's Oxford campus, with the Cathedral of Learning at the center of a grassy Quad, and surrounded by other Late Gothic Revival-style buildings to house other classrooms, offices, and residences. Of that grand plan, only the Cathedral was actually realized:

The top of the Cathedral hits 535 feet, and there are 42 floors. It is the tallest educational building in the Western Hemisphere.

Adjacent to the Cathedral of Learning is the rather more modestly sized Heinz Memorial Chapel.

According to the University of Pittsburgh's on-line Campus Tour, the chapel is

"Open to campus religious groups of all denominations, as well as the public, Heinz Memorial Chapel is a popular site for religious and memorial services, concerts, guided tours, and weddings. Each year, the chapel hosts between 170 and 190 weddings, which are restricted to

Pitt students, alumni, and other affiliates, as well as employees of the H.J. Heinz Co."

David Giffels on the Rust Belt:

"The Rust Belt is the burden of America, and I don't mean in the sense that the rest of the country has to shoulder us. I mean in the sense that the 70 percent of us who have stayed have endured and tested and defined the burden in a way that might provide insight for a country that, lately, might welcome our lessons. We know the weight. We understand hard times. We've been called 'dying' but haven't died. We know a few things.

If you want to nutshell the story of the American Industrial Belt, it's an ongoing narrative of arrival and departure. We understand America by virtue of living in melting pots that never completely gelled, and we understand America by virtue of living in places people had to leave.

Many [migrants and immigrants] settled . . . the culture matured. The culture of hard work and bowling trophies and Blatz and Pontiacs became a linchpin of Americana. But the notion of this new middle-class lifestyle as "having arrived" was a falsehood.

Sometimes I wonder if some of these cities were too big for their own good, often cramped and underplanned and overreaching . . . A few years ago, Youngstown [Ohio] mayor Jay Williams launched a campaign called "Youngstown 2010," a systematic plan to "right-size" his city, whose population plummeted from 167,000 in 1960 to 67,000 in 2010. The idea was to eliminate vacant houses and neighborhoods . . .not to be ashamed of the reduction, but to resolve it."