"Tenement house with children in front. Possibly 36 Laight St. Location: New York, New York (State)." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1910. {2}

Tenement...(especially in Scotland or the US) a separate residence within a house or block of flats. (also tenement house) a house divided into several separate residences. {3}

By that definition, a tenement should be just one more version of a space to live. Maybe less space than you'd have in a single-family house, but maybe more than in a log cabin. I suppose I could say I live in one myself, as my dwelling at the time of this writing is the second floor of a house built circa 1880 (which has more space than many log cabins did, plus indoor plumbing!).

If the word "tenement" can call up anything in popular imagination, though, the imagined scene would probably be more like that in the photograph at left than just any apartment block or split-up old house. But "tenement" has a certain weight, carried by photographs and news stories, by exclamatory indictments written to "shine a light" on the sorry conditions of the poor in the cities. "Tenement" became synonymous with words like "slum" and "blighted” (terms which have remained in our contemporary vocabulary, while “tenement” has faded). “Tenement” could be used like shorthand to indicate that a place and those who resided there were less than fortunate, or that they and their lives were antithetical to ideas of what society was supposed to be.

Such shorthand and the attitudes behind it happened because the years of Industrial Revolution ushered in a new "economic model," which changed not only how masses of people lived and worked, but also saw intensified feelings about race, class, and nationalism.

"Distant View of Boston." John Rubens Smith, circa 1809. {2} The kind of pastoral scene Jefferson wished for in his yeoman dreams.

Back at the beginning of our Republic, Thomas Jefferson dreamed of a nation of "yeoman farmers," an agrarian populace plowing half-sections in rural counties, far from the hustles and bustles and possible corruptions of cities. That dream found a measure of realization over the next hundred -plus years with the homesteaders: families that bravely pushed into the West, into the forests and out on the prairies, to set up house and home and "bootstrap" their farms on the frontiers. Those rural people have been granted a foundational place in the American Mythos, right up there with the Founding Fathers, exemplary of what it means to be a "real American."

The decades of the homesteading frontier families, striking out from the east, were conversely concurrent with decades of increasing urbanization. Contrary to anyone's agrarian dreams, people were moving to cities and towns, or never getting out of them in the first place, a population shift that has not stopped yet. As the homesteaders went west, a range of factors impelled that opposing shift: mechanization, economic upheavals, globalization, investing as a means of increasing wealth, the widespread us of the patent right, the protection of corporate interests by governments, the first glimmers of what we've since come to call "consumer culture," and most anything else readily accepted today as elements of conducting business all came into recognizable shape with the rise and expansion of massed industry. With these came, too, the middle class -- and the working class. The working classes, the laboring poor, were the inhabitants of the tenement districts, and their labor was absolutely essential to the expanding middle class and the growing wealth of the industrialists. Yet the working poor were usually viewed as being "un-American."

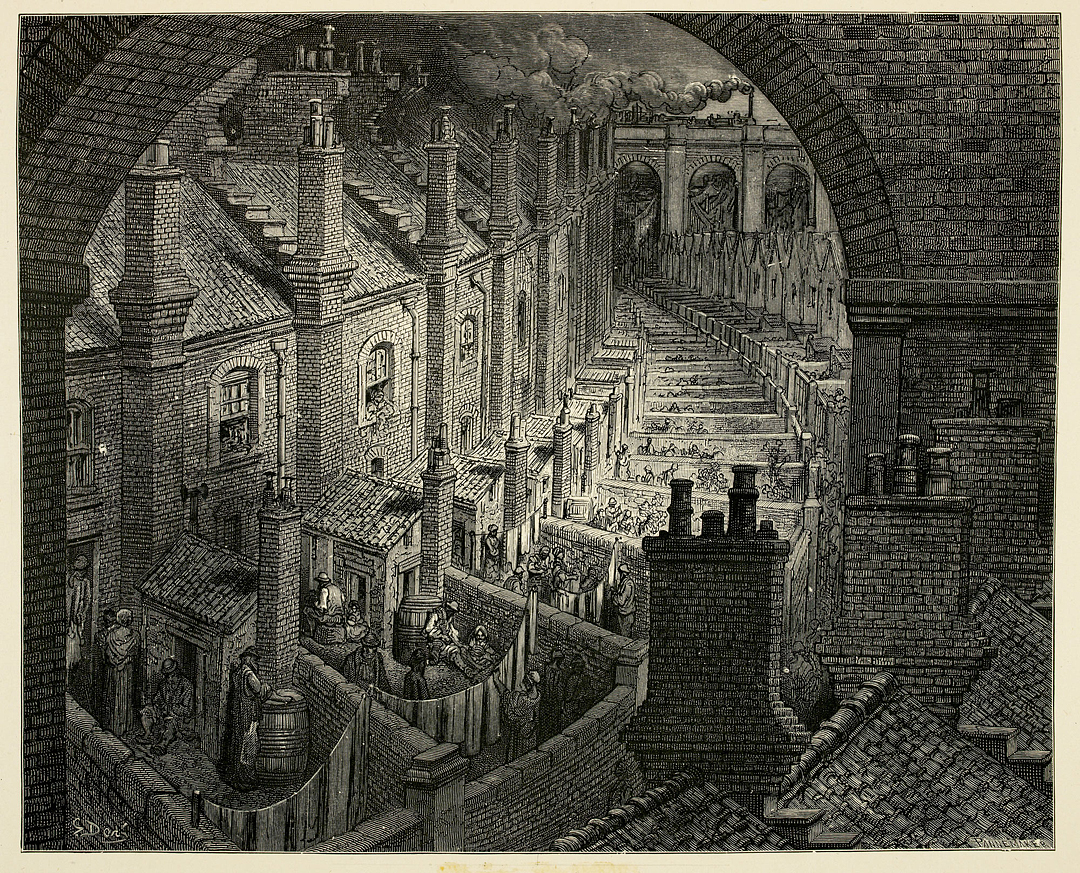

Illustration by Gustave Dore for Jerrold William Blanchard's London, A Pilgrimage (1872) {4} Is this the most famous image of tenement life? I'd think it certainly ranks pretty high up the list. At least three times this was a reference for scene designers on productions of A Christmas Carol that I've worked on.

As the Industrial Revolution swept out of the English Midlands to North America, it was accompanied by people who left Europe or the Far East for the "New World" in hopes of finding better work, to work off debt, to leave behind socio-political troubles, to maybe (as has been oft noted in history books) provide a better future for their children. The United States was seen as a place where there was space, physically or economically, to attempt for better than what was available in the "old country." Some would move right through an entry point and head for Ohio or Wisconsin or Nebraska and homestead themselves; others remained in the cities, and worked for someone else.

"Vast weaving room in the White Oak Cotton mills, Greensboro, N.C." H.C. White, 1907 (from a stereo view). {2}

The U.S.-born migrants might have believed that they had little opportunity in rural districts: women seeking economic independence, or adult men from large families who found it difficult to get land of their own; collection on debts could leave some without land or other livelihood; anyone that was affected by changing modes of transportation or deflation in currency. Anyone could move to a town or city that promised employment and wages.

"The transformation from an agricultural to an industrial economy...produced social dislocations so unprecedented as to require new words, such as urbanization, a term coined in Chicago in 1888 to describe the migration from farm to factory and the explosive growth of America's industrial cities. Just over half of American workers in 1880 worked on farms. By 1920, only one-quarter remained on the land. Crowded into tenements, urban workers confronted substandard housing, poor sanitation, and recurring unemployment." {5}

"Cottage Street hovels down by the river in Easthampton, Mass., in which a great deal of home work is done on suspenders..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

"A row of houses of the cotton mill people. Lydia Mills, Clinton, S.C..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1908. {2}

But whether they entered from the rural counties, or were "just off the boat," those that did not move on to the rural West had to take such employment as they could find, and take what residence they could afford, and that was usually in the tenement districts: the apartment buildings and mill town-houses. Their children might remain, too, though succeeding generations would, sooner or later, find a way "up and out" of the tenements. That their ethnic background, laboring status and residence would have them seen as antithetical to "real Americans" sprang from attitudes towards the working poor generally, and the looming questions of money and social status.

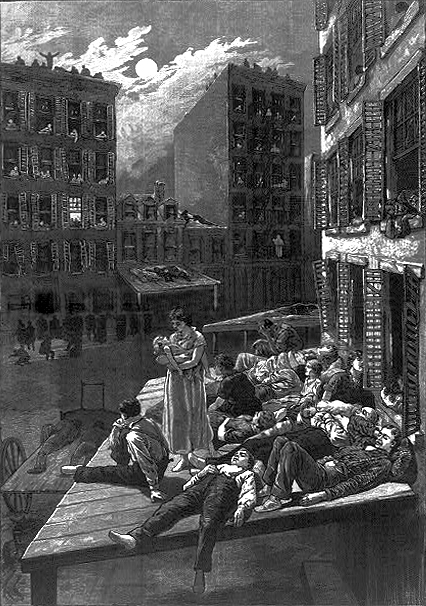

"New York City - The recent 'heated term' and its effect upon the population of the tenement districts. A night scene on the East Side." By a staff artist at Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1882. {2}

Cities and towns, yesterday and today, struggle to accommodate the populations that live within them, whether in terms of numbers or of "affordability," whether established residents or the recently arrived. Tenements weren't planned; more like they "just happened;" no one really had any idea how to handle the influx of people. In some cities and towns, the need for housing was met (if you can call it that) by landlords dividing already existing structures into ever smaller spaces, or later by contractors putting up, as quickly and cheaply as possible, platted blocks-full of single-family houses, or individual plots of three, four, five, or six-story, high-occupancy buildings. Some migrants sought to alleviate the problem of affordability by subletting rooms to individuals or other families and living elbow-to-elbow with them.

When older housing was converted to tenement use, it was, well, already old: floors, roofs, wall coverings would already have been subjected to years of wear and tear which would thence go untended. If it was purpose built, it wasn’t necessarily cheap and poorly constructed, but it probably was. Tenements were put up for rental and quick turn-over, not purchase or extended residence; they weren’t built for comfort, they were spare and utilitarian, not worth much investment, rather like the residents were seen by the landlords and employers.

What the born citizen or the newly arrived found when they got to the cities was nothing like what they expected.

" 'How the other half lives' in a crowded Hebrew district, Lower East Side, N.Y. City." (From a stereo view) Underwood & Underwood, circa 1907. {2}

“I needed sadly to readjust myself when I arrived in New York. ...the East Side Ghetto...upset all my calculations, reversed all my values, and set my head my head swimming.

I have not forgotten and I never can forget that first pungent breath of the slums which were to become my home for the next five years...how depressed my heart became as I trudged through those littered streets, with the rows of push-carts lining the sidewalks and the centers of the thoroughfares, the ill-smelling merchandise, and the deafening noise. ... This was the boasted American freedom and opportunity -- the freedom for respectable citizens to sell cabbages from hideous carts, the opportunity to live in those monstrous, dirty caves that shut out the sunshine.

...what were they doing here in this diabolical country? Well, here was one selling pickles from a double row of buckets...another, laboriously pushing a metal box on wheels and offering baked potatoes and hot knishes to the hungry, cold-bitten passers-by..." {6}

Early on, tenements were not so much different from other structures, and those older houses would have begun as fairly respectable dwellings, with fairly respectable tenants or owners. However, it has long been common for those with the cash or credit to “move up” to newer addresses: they followed their peers; they sought locations farther away from expanding industry; they wanted to increase the distance between themselves and the poorer folk, and decrease their separation from the wealthier. The housing stock they left behind became ripe for tenement dwelling, and landlords did what-ever they felt was in their own interest.

"End of the poor -- Funeral from a tenement house in Baxter Street, Five Points, New York -- from a sketch by our artist." Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1865. {7} The Five points had the reputation of being the worst of the worst of the slums.

"...the majority of the working class saw their living standards deteriorate... - [because of] the rapidly rising rents exacted by those...called 'mercenary landlords' - but primarily because constructing housing for poor people wasn't profitable. Some speculative developers did erect three-story brick structures, partition each floor into four rooms, and rent out each of six two-room 'apartments' to one or more families...

On the whole, however, speculative builders - especially those operation on thin credit margins - had little incentive to house the poor. Nor did established landlords have reason to replace their rundown, two-story, brick-fronted wooden houses with better structures....landlords harvested tremendous rents just by packing people into preexisting buildings. Indeed, the more they reduced maintenance and let their properties deteriorate, the more the city reduced their tax assessments, thus boosting their profits." {8}

In some places, new construction was shoe-horned into the scant spaces behind and between already existing buildings, to increase the profitability of a given plot of land. Eventually, though, those old housing stocks would prove insufficient, even when they had been packed with tenants like the storied sardine tins. Developers did begin to build new dwellings as the migrations continued and increased, but with profit ever in-mind, conditions were hardly guaranteed to improve. “Monstrous, dirty caves” blocking out the sun would become a fitting description.

"New York, N.Y., yard of tenement." Detroit Publishing Company, 1910. {2}

"...the cumulative market power of even poorly paid laborers and artisans was so great the tenement construction became profitable. Some of the new three- to five-story buildings...were solid brick structures. Many however, were... 'so slightly built that they could not stand alone, and, like drunken men, require the support of each other to keep them from falling.' ... Most were stripped-down, amenity-free versions of the row houses developers were raising for the middle and upper classes elsewhere... Most lacked 'modern improvements,' apart from stoves, and were seldom linked up with water or sewer mains: working people used bedpans and privies long after the respectable classes had switched to water closets."

Those above-mentioned privies were supposed to be regulated but were usually neglected. The least of the poorer structures, privies were often dug too shallowly, they were crudely covered, and they leaked: effluvia seeped into nearby basements (also occupied by the poor!) and they overflowed during heavy rains, which sent their contents running down the alleys and into the streets. {9}

"9 year old girl carrying garments down Blackstone Street, Boston, Mass., to a Hanover Street home. She finishes 8 pairs of trousers a day and gets 8 cents a piece..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

Homestead, Pennsylvania (foreground), with the Carnegie Steel Company's Homestead Works (background). {10} Homestead went from a sleepy little riverside town in 1881, with a population of about 600, to a small city of about 12,000 within ten years. Around a third of the residents were employed in the mill. At least until after the Second World War, the majority of them likely walked to work.

And those streets took on principle roles in lives among the tenements: they were where items were bought and sold, where food was purchased, where some people slept, and were how employees got to work. While mass conveyance was becoming more common, its use was enjoyed most by those who could afford to pay the fares and had reason to go from distant place to distant place. For the lower-income population, they could neither spare the fare price, nor did they travel far. They lived near to their jobs out of necessity: walking to work was free, and rents at a distance were higher. Plus, even if they had the funds for a better address, they might not be able to get past the landlord. The following passages concerning Manhattan's pedestrian workers and their environs are specific, but the same could be said for many industrial employees and their cities:

"...the bulk of the working class -- still unable to afford public transportation -- had to live near their jobs. For most this meant Manhattan's rim, the tenement-lined streets leading back from the docks into a mixed terrain of heavy industry and light manufacture. The twenty-five thousand ironworkers walked to great foundries rooted on the East and Hudson river shorelines, near their rail and sea life-lines...

The proximity of community to industry cast a pall over daily life. Admixed with foundries and factories were reeking gasworks, putrid slaughterhouses, malodorous railyards, rotting wharves, and stinking manure piles, which gave the working-class quarters their distinctively fetid quality...” {11}

"The Big Pennsylvania hole (for station), N.Y." Detroit Publishing Company, 1908. {2}

The four city blocks-worth of buildings in the Tenderloin district of Manhattan (described in the passage below) that were demolished for this "hole" would have been similar in appearance to the structures that are now visible here.

When the Pennsylvania Rail Road prepared to dig tunnels under the Hudson River to allow its trains to transit directly to Manhattan (or under the city, rather), the company committed itself to buying four whole blocks of city on the West Side for what would become the site of their massive Pennsylvania Station (as seen in the "hole" above; the site was dug and graded several stories below street level before building construction commenced). William Baldwin, president of the Pennsy’s subsidiary Long Island Rail Road, made an inspection of the Tenderloin district in 1901 to see just what the company would be displacing, and his walking tour provides this example of a working class neighborhood:

"As [he] walked toward the river along West Thirty-second from Seventh Avenue with its dingy old frame storefronts...he found a dirty, busy street lined with small shops, a Chinese laundry, 'cheap, low-class Italian tenements...and the Industrial School of the Children's Aid Society on the corner, which is the only building of any consequence.' When the federal census taker had come through a year earlier he had recorded many Italian families with lodgers, as well as Jews and Irish, working as waiters and tailors.

On one block small boys in knickers and girls in pinafores gathered round the itinerant knife sharpeners. The next block north was heavily black, families from Georgia and Virginia escaping the Jim Crow South. It was all a bit rough and there were clumps of young men standing about...They toiled as railroad porters, hotel porters, waiters, launderers, stable hands, and cooks. …

When Baldwin crossed the filthy cobblestones of Eighth Avenue, the stench of the stockyards was just discernible when the wind blew off the Hudson. Continuing on toward the river, he found on both sides 'decent, respectable, but cheap grade apartment and boarding house, the entire block.' ..."{12}

"This is the condition in which I found the lower hall at 266 Elizabeth St., N.Y.... It is a licensed tenement and finishing of clothes was going on in the homes..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

As more tenements were built, they were put up on the poorest land, land that had been passed over for development for the better-off customers. Marginal land was better for the developers who built tenements, anyway, as the cost of the purchase could be easily recouped. Damp lands along rivers, already distressed acreage just outside the mills or mines, up hills that were difficult to traverse, plots that were downwind of a noisome business - anywhere that those with money found undesirable could be squatted by the poor, and built on by the developers.

"A little spinner in the Mollahan Mills, Newberry, S.C. She was tending her 'sides' like a veteran, but after I took the photo, the overseer came up and said in an apologetic tone...'She just happened in.' ... The mills appear to be full of youngsters that 'just happened in,' or 'are helping sister.' ..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1908. {2}

"These are some of the sweepers and mule room boys working in Valley Queen Mill. River Point, R.I. Several of the smallest ones there said they had been working there 3 years and over. Spoke no English..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1909. {2}

That great numbers of people were massing themselves into tight, urban environments was not exactly new – London had teemed as the largest city in the world for a couple of centuries already. That they would be employed on a mass scale (“twenty-five thousand ironworkers”?) for some type of monetary recompense was new, and a result of industrialization. Before that "work" had been done for different reasons:

"For nearly all of recorded human history, the notion of laborers selling their labor services for wages was nonsensical. Labor was the compelled agricultural toil of social inferiors in the services and under the command of their betters. In the United States, this remained true well into the nineteenth century. The value of labor depended on what the worker was -- free or slave, man or woman, native or immigrant, propertied or hireling -- not what the worker produced or wished to consume.

Race notoriously demarcated slave and nonslave, but invidious distinctions were made everywhere. Women, children, indentured servants, immigrants and unpropertied white men were all treated as social or biological inferiors (or both) to propertied Anglo-Saxon men. Who the worker was, as defined by some amalgam of biology, law, and custom, dictated the nature of the work they did and how that work was valued. The value of labor was not determined by what a worker did. What a worker did was determined by his or her social value.” {13}

"Entrance to licensed tenements, 170-172 Thompson Street, N.Y. where home-work flourishes..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

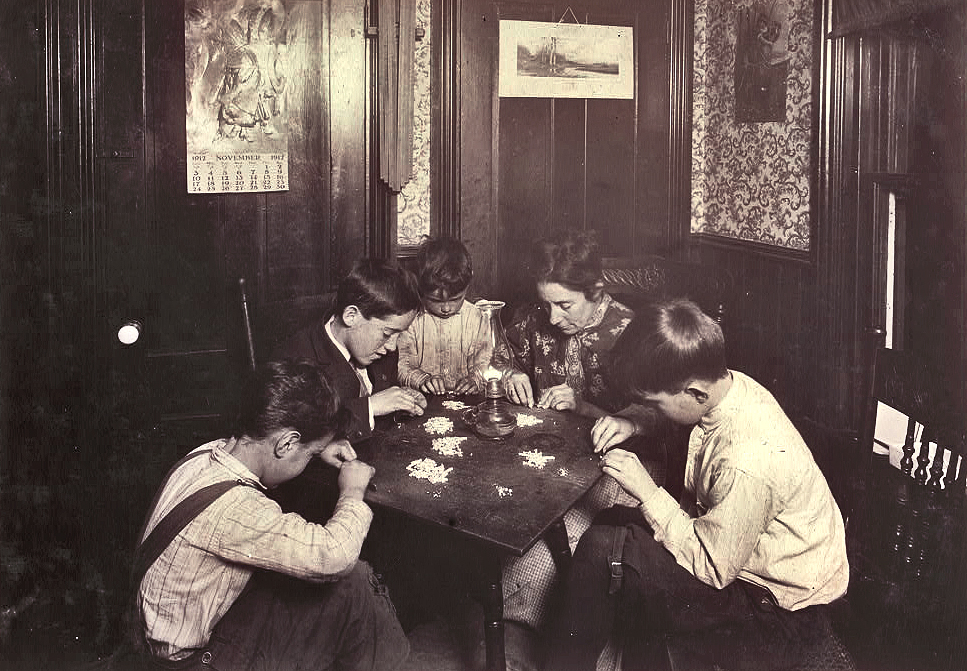

Piece-work jewelry: "Mrs. Gay, 33 James Street, Attleboro, Mass. and children...There were 244 stones in this lot. She said they earned about $5 a week when all worked steadily...Work after school and evening until 8 P.M. or after...Father works in factory..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

Dearly held notions, those “invidious distinctions” colored how many U.S. citizens would view a great number of the people who arrived in America after independence. As the nation, industry, and immigration expanded through the Victorian era, a distinction was drawn between an “American Race” and everyone else. “Americans” were of Anglo-Saxon stock, and they were Protestant. The most respectable of them would trace their lineage back to the Colonial era, or pre-Colonial if possible. The majority of the middle- and upper classes were of the “American Race,” and the later immigrants who did not fit easily into such categories would find it hard to achieve acceptance in American society, even if they did have the monetary means. The internal migrants, or their children, might have a better chance at moving up the “social ladder” provided they were Anglo and Protestant, but there was no guarantee.

" 'Everybody works but----.' A common scene in the tenements. Father sits around. 'Sometime I make $9.00, sometime $10.00 a week on the railroad; sometime nottin' ' Helen, 5 years old, and Adeline, 10 years old, help pick nuts. Tessie a neighbor, helps too...All together they make $4.00 a week..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1911. {2}

The settlers of Jamestown and the Puritans of New England looked upon the Native Americans and the blacks imported for slavery as barbaric, heathen, lazy and duplicitous. With the passing centuries, those kinds of beliefs would find more people to focus on.

"When [Lewis Wickes] Hine was making his photographs...in the early 1900s, Americans were less sentimental about immigration. Immigrants were expected to do hard, dirty, dangerous work...but many Americans could not agree on the character of the immigrants. There was a widespread belief among natives that earlier generations of immigrants from Ireland, England, or northern Europe...were fine people...the millions of 'new' immigrants who arrived from eastern and southern Europe starting in the 1890s...particularly the Jewish, Slavic, and southern Italian -- were accused of virtually every form of moral and social depravity...not only by unwashed bigots but also by well-educated and prestigious white gentlefolk." {14}

"Young women and young man reading by the light of a patented lamp." National Photo Company, circa 1909. {2}

The Americans of the middle class held the “middle class-jobs:” they were the accountants, the managers, the banking assistants – call them “white collar.” They worked within, and got the majority of the benefits from, that new economic model of businesses and contract obligations, they looked forward to social advancement (and better housing), and viewed themselves as something new and better. Yet that economic model was made possible because of the working poor of the tenements, whose labor was integral to the changes in society that made the middle class possible in the first instance:

"...the middle-class Victorian family depended for its existence on the multiplication of other families who were too poor and powerless to retreat into their own little oases and who therefore had to provision the oases of others...The spread of textile mills, for example, freed middle-class women from the most time-consuming of their former chores, making cloth. But the raw materials for these were produced by slave labor. Slave children were not exempt from field labor unless they were infants...

Domesticity was also not an option for the white families who worked twelve hours a day in Northern factories and workshops transforming slave-picked cotton into ready-made clothing. By 1820, 'half the workers in many factories were boys and girls who had not reached their eleventh birthday.'... In 1845, shoemaking families and makers of artificial flowers worked fifteen to eighteen hours a day, according to the New York Daily Tribune. ...

Within the home, prior to the diffusion of household technology at the end of the century, house cleaning and food preparation remained mammoth tasks. Middle-class women were able to shift more time into childrearing in the period only by hiring domestic help...

For every nineteenth-century middle-class family that protected its wife and child within the family circle...there was an Irish or a German girl scrubbing floors in that middle-class home, a Welsh boy mining coal...a black girl doing the family laundry, a black mother and child picking cotton...a Jewish or an Italian daughter in a sweatshop making 'ladies' dresses or artificial flowers for the family to purchase." {15}

Those “invidious distinctions” provided reasons for lower wages paid to the laborer. Paying the most recent hire a lower wage was and is common, but the distinctions put the industrial worker, especially the immigrant, at further disadvantages from their lack of fluency in English, and their lack of any social status. They were seen to deserve the least amount that an employer might pay. Plus, as there were always people looking for work, a boss had no incentive to keep anyone. If a laborer didn't want the wage offered, or failed to perform and was fired, someone else – “the next guy in line” -- would take up the task. Paradoxically, because the immigrant or the dislocated worker would take what-ever wage was offered, they were believed to be driving wages down, maybe even purposefully: a “race to the bottom” that hurt society at-large by ruining the earning power of real American workers.

"Mrs. Tony Racioppo, 260 Elizabeth St., N.Y. 1st floor rea, finishing pants in dirty tenement home. Althou [sic] it is a licensed house, the whole place is very much run down. The ahllway [sic] is in the same condition as that one at 266 Elizabeth... [see photo above] Baby had bad cough. Mother said recovering from measles..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

It was also believed that it was “in their nature” to take the lower wages: the immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, the Chinese, the blacks from the South, were viewed as inherently less intelligent, inherently cheap and slovenly, and inherently disrespectful of white Protestants and the Protestant work ethic, so they obviously had no want to ask for better pay. That they had large families showed that they lacked the good graces and self-restraint that was believed to be a natural trait of the Anglo-Saxon. That the working poor lived in cheap housing, near the industries, where sanitation was an after-thought, that their residences were over-full and sublet, that their large numbers of children were tired, dirty, and unschooled, were all seen as part of their “natural” state. That the tenements were slums was shown as further evidence of the lower class' being a lesser people – a lesser race.

Taking all of those considerations together, the working poor would even be seen as detrimental to the continued existence of the “American Race:” with their increasing numbers, large families of dirty children (who would someday be dirty adults), their naturally lesser race status, they threatened to literally overwhelm the real Americans and deliver the country into the hands of barbarism, just as the Goths had sacked Rome. By the turn of the 20th Century, there was a growing belief that something had to be done, including the introduction of “eugenics:” scientifically-based selection of traits to ensure that the best humans (id est members of the already better American Race) would multiply and maintain dominance. The lesser races would be weeded to manageable levels, whether they were native born or had immigrated (being native born didn't exclude one from such beliefs). To that end, among other programs, many states allowed for the forcible sterilization of the “feeble minded” or the “imbeciles” so that they would not have similarly imbecilic children. Of the tens of thousands that were sterilized, a great many were native born and white, but also poor, young -- and women. But – that's so another story. {A}

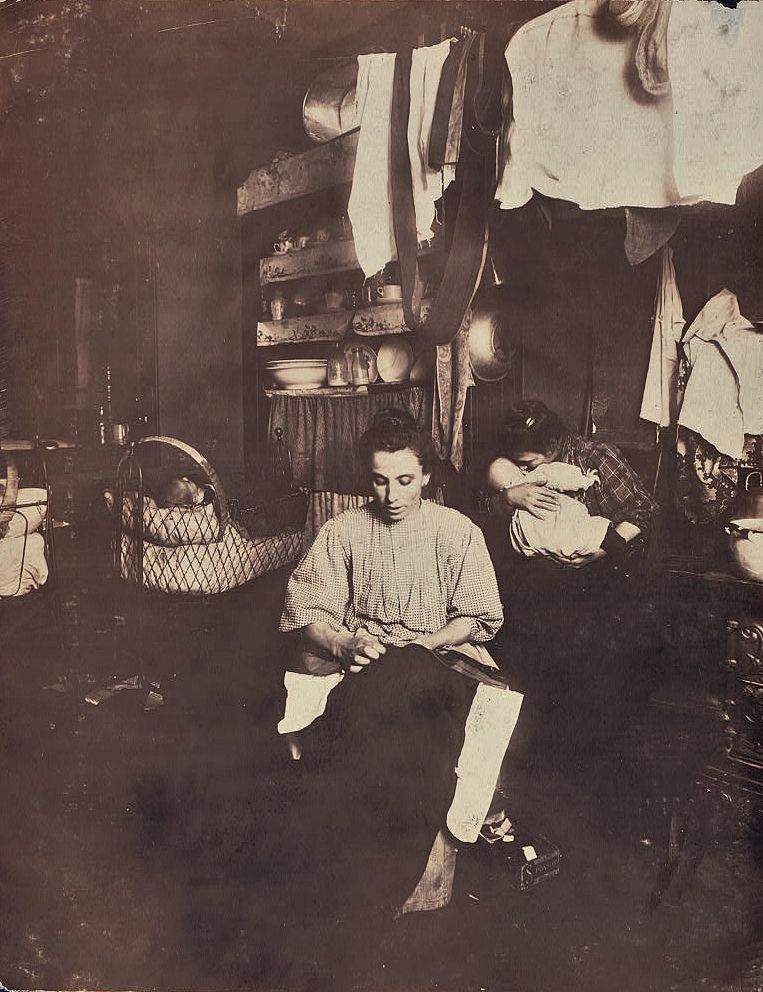

"This is typical of the home work on underwear in these quarters. Mother and children and surroundings all filthy. 4 Me Culphe Place, Somerville, Mass..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

The middle class Victorians also promoted a different family arrangement for themselves: the “nuclear family.” In this ideal family, the members would find everything they needed for domestic security, and maybe bliss, without the obligations of an extended family. The husband and father, who did the real work in the business world; the wife and mother, who tended to “hearth and home” and saw to her husband's personal welfare when he wasn't doing business; and their children, who were expected to pay attention, learn their school lessons, and enjoy some playtime unencumbered by want.

It was a self-propping unit free from the old-fashioned family whose members lived near to one another, if not under one roof; who worked together as an economic unit. But that was pre-industrial, before the middle class. Except that many of the working poor, in their tenements, continued to live and work within that extended family model to “make ends meet” under the industrialized model.

"Making artificial flowers in a New York tenement house." National Photo Company, circa 1909. {2}

“Many producing households resembled the one described by Mary Van Kleeck of the Russell Sage Foundation in 1913: 'In a tenement on MacDougal [sic] Street lives a family of seven -- grandmother, father, mother and four children aged four years, three years, two years and one month respectively. All excepting the father and the two babies make violets...'

By the end of the nineteenth century, shocked by the conditions in urban tenements and by the sight of young children working full-time at home or earning money out...middle-class reformers put aside nostalgia for 'harnessed' family production...[and blamed] immigrants for introducing such 'un-American' family values as child labor." {16}

Of course, ideals in family arrangements can wax and wane in popularity:

"In the late 1920s and early 1930s...social theorists noted the independence and isolation of the nuclear family with renewed anxiety. The influential Chicago School of sociology believed that immigration and urbanization had weakened the traditional family by destroying kinship and community networks." {17}

How to help those communities and networks of the working poor was a subject that was addressed by generations of reformers locally, and nationally by the Progressive movement. However, their interest in reform and progress was as much influenced by “invidious distinctions” as those who would take no positive action.

"Entrance to tenements, 53 to 59 Macdougal St., N.Y., (licensed) in which coats and flowers are made..." Lewis Wickes Hine, 1912. {2}

"Progressives did not work in factories; they inspected them. Progressives did not drink in saloons; they tried to shutter them. The bold women who chose to live among the immigrant poor in city slums called themselves 'settlers,' not neighbors. Even when progressives idealized workers, they tended to patronize them, romanticizing a brotherhood they would never consider joining." {18}

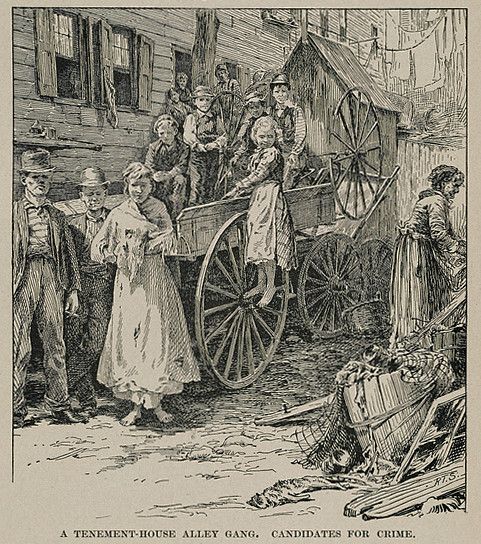

Book illustration: "A Tenement-house alley Gang: Candidates for Crime." Darkness and Daylight, p 485, 1897. {2}

And of course there was the question of crime. I suppose it's no surprise that the group in the illustration at right would be referred to as a "gang." Then, as now, "gang" carries the prospects of illegal and/or violent behavior. Then, as now, it's hardly unusual for some of the less-well-off to turn to “getting by” with what-ever means they might find necessary or expedient. The Tenderloin district, for instance, where the Pennsylvania Rail Road was going to come up for air, was notorious for its criminality.

"Anyone abroad in the Tenderloin late at night had to beware. In the tenebrous side streets the hardened criminal classes held sway, and brazen streetwalkers lured unwary rubes to panel houses where sliding bedroom walls made stealing watches and wallets easy. Murder was not unknown either. Just as Wall Street gloried in its fearful financial power, so the Tenderloin gloried in its lurid menu of vice and corruption...just as many a tourist had to see Wall Street, so many of the men among them had to see the Tenderloin." {19}

(I think its reasonable to believe that the vast majority of the working classes never engaged in such activity. Then, as now, most people don't commit crimes, at least not of any seriousness, while the actions of a small percentage of a population can be transferred as fact to the larger. And I'm not even going to try to get into the subject of Tammany Hall or the political “machines” of the major cities that patronized the tenement residents, grabbed vast sums of money, handed out patronage jobs like second-line throws, and made distinctions between "honest graft" and "dishonest graft." There are plenty of texts on those already.)

The illustration is from a book by missionary Mrs. Helen Campbell, entitled Darkness and Daylight - or - Lights and Shadows of a New York Life, (a long title, but common for the era) which presents to the reader a kind of "inside view" of life among the city's tenement houses and side streets, the "little known phases of New York life" as the subheading puts it. Mrs. Campbell writes:

"Can any thinking man hazard the assertion that criminals are not born and reared in such a region of filth and degradation? Assume that poverty compels human being to mass themselves, it does not follow, as is generally supposed, that the actual necessities of living are lessened in any way. The reverse is the fact, for with crowding comes indulgence in vicious habits and practices, disease and death...

Persons arrested for intoxication and disorderly conduct arising therefrom, in a large percentage of instances, are fined only small sums by the police magistrates, or sent to the city prisons in default of payment. What is the effect? The family of the offender are often deprived of the necessities of life by the enforcement of a fine, or are left wholly without means by the husband's or father's incarceration. Necessity compels a resort to crime that the family may not starve. Wages of tenement-holders are at all times small and scarcely adequate to the maintenance of their families; and when from the small wage is taken a fine, or the wage-winner is prevented from earning his scanty pay, the family dependent upon him must suffer. The inevitable result is almstaking or crime..." {20}

The missionary and reform work, the ideas and legislation proposed and passed by the Progressives, would eventually have some positive effects on working class lives. Public outcry (however fleeting) over well-reported industrial disasters did push the elected at all levels of government to enact laws that would prevent needless injury or death – and the working people themselves did their best to take control of their situation. Moving through the 20th Century, a great many factors affected the lives of the working class, and for some, radically changed how they lived. That wouldn’t really happen, though, until after Depression and War.

Above: "The 'crackerbox" housing eighty-seven people. Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania." Right: "Tenants living in the crackerbox. Slum tenement in Beaver Falls..." Both by Jack Delano. {2*}

Photographers employed by the federal government during the Great Depression {B} shot thousands of images to document the lives and lands of the “common man” or the “forgotten man,” many of which are now in Library of Congress collections (like those above). Their main focus was initially on agricultural life, but their efforts quickly widened to include the living and working conditions of lower-income people generally.

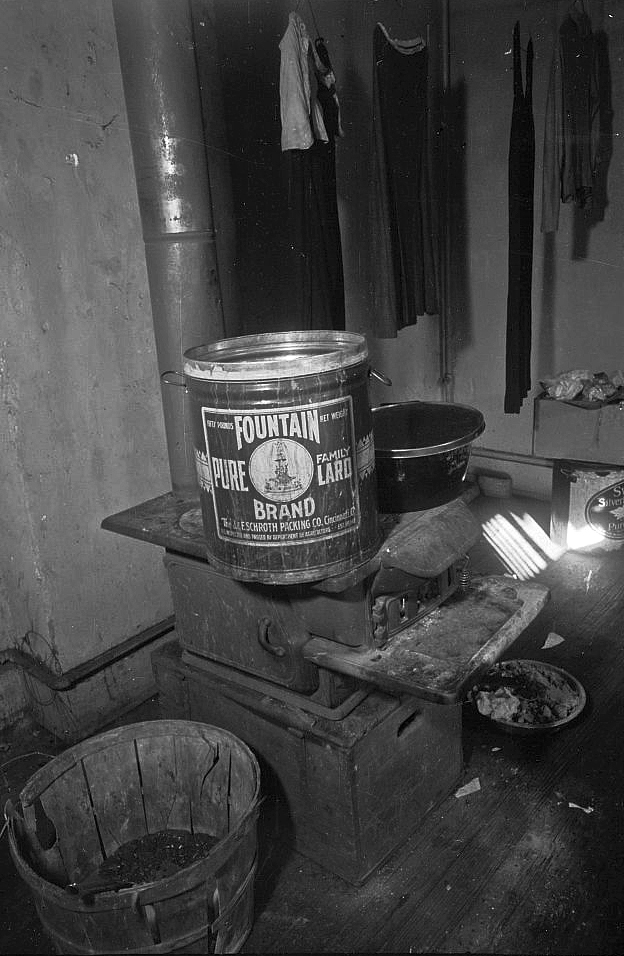

One of those Library collections depicts housing conditions in Hamilton County, Ohio, taken by Carl Mydans in 1935 {2}. Some of those follow:

"Tenement kitchen shambles..."

"Alleyway off Van Horne Street..."

"Bed and sitting room..."

At left: "Kitchen for two families..." At right: "Three-family toilet..."

"Levittown houses. Peg Brennan, residence at 25 Winding Lane." Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., 1958. {2} Yep, that Levittown, Long Island, New York.

The story of the tenements doesn’t really end with the Great Depression, of course, nor does it end in the post-Second World War “housing boom.”

The middle class expanded its ranks again, becoming more “inclusive” than it had been, encompassing many families who would never have imagined such prosperity a generation or two before, and those most recently inducted into the middle class life slowly but surely left the tenement districts. As they moved to “the suburbs” to enjoy “the good life,” their old, run down city housing units would again change hands.

East Mall high-rise, in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Date and photographer unknown; I'm guessing circa 1985. {web} The building straddles Penn Avenue at Penn Circle (now renamed Euclid Avenue), and was part of a multi-block "urban renewal project" constructed in the mid-1960s. Finished by 1970, they were decrepit before 1990. I can well recall driving along Penn Avenue, under this hulking behemoth of a structure, and wondering "Who in Hell thought this was a good idea?!"

The old-line city centers, the “urban core” areas, the “inner cities,” where the tenements still stood, now saw other migrants move in: blacks from the South, Puerto Ricans moving to the mainland, the dislocated from Europe, and later from South East Asia, would become part of that deep successions of tenement residents who had aspirations for better lives. They had to face some of the same old “invidious distinctions” that had beset the previous tenants, though, and also faced the efforts of “urban renewal,” which literally changed the city-scape around them.

If there is a common conception of “the tenements,” it’s most likely of the tenements in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, when the reformers, photographers, and journalists were most active in their attempts to bring about some kind change for the working poor; but the tenements existed well before and well after that period of intense scrutiny (arguably still existing today,though not referred to as such). The story of the “mill towns” is, if anything, even more obscure, but is just as important in the history of the working class. The history of the working class is important because they were behind, or perhaps underneath, most if not all of the major improvements that made the expanding national economy possible.

Their inclusion or exclusion from the story of the United States has much to do with who wrote the history books. The kind of texts we recognize to day as “history” were written in the first instance by middle class historians in the mid- to late 1800s, and they had a particular narrative they wished to inculcate in their readers: it was about the white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant; the story of the “real Americans;” a show of how great the middle class people were; and how intrepid the homesteaders who struck out on their own in the wilderness of the Frontier.

Backstopped by the “invidious distinctions,” that story was told for over a century; the working poor, being “un-American” and disposable, were not part of that story; neither were the tenements and slums they lived in. The tenements are little remembered now, or not remembered well; the working poor are neglected or remembered for the wrong reasons; the slums are recalled, and still reported on today, as islands of vice because they were not reported, are not reported, with much measure of fullness. I have to wonder, too, if there was a willfulness in that under-reporting, not just out of a real or feigned belief in the classes and their rankings, but out of fear: to really delve into the story of the nation and include the real stories of the working classes and the tenement-bound poor, would have meant delving into the underlying causes of poverty and the role of capitalism as constructed by middle- and upper class Americans.

Many of our current authors are publishing stories that examine much more broadly the history of the nation, so perhaps those "un-American" poor will be seen from a different perspective in future.

NOTES:

Yes, much of this does concern the tenements of New York City, but they may have received the greatest amount of scrutiny during their existence, and may well have the most information written about them, then and now. I don't thing it's "going out on a limb" to generalize across the national scene: New York's tenements might have been bad, but tenement life and mill town living was lousy in many places, whether inside a city's limits, or out on a hillside near a coal mine. The general attitudes toward the working class, the notions of what the poor were versus the other classes, were pretty wide-spread.

{1} Thomas C. Leonard, Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics & American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016. p 3.

{2} Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. (Minor processing of images by the author, 2018, 2019.)

{2*} Among the collections of the Library of Congress are photographs taken by Jack Delano in and around the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, region; their dating shows what I believe is a discrepancy in the record, however. The exterior of the “crackerbox” is noted as “1941 Jan.,” while the interior (with tenants) is noted as “1940 Jan.” The other photographs credited to Delano also have those two years noted, though a close observation of two of images shows that they were taken within a short time of each other. All of the photographs are noted as having been taken January (with one exception that was shot in February of 1941).

I will allow that it might be possible that Mr. Delano made two trips to Pittsburgh, both times in January, but one year apart; however, as more of his photographs are noted as having been taken in 1941 and all show like amounts of snow in the environment, I am more inclined to believe that, across multiple rolls of film, one of two things occurred: either Delano's notations were illegible, and someone made a “guess” at the date when creating the original record; or, the date was simply entered incorrectly. I am also inclined to believe that all of the photographs were taken in 1941.

{3} Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson, Editors, Concise Oxford English Dictionary (11th Edition). Oxford, U.K., New York, N.Y. : Oxford University Press, 2004. p 1484.

{4} British Library, Victorian Britain collection items: London illustrations by Gustave Dore.

{5} Leonard, p 3 & 4.

{6} M.E. (Marcus Eli) Ravage, “My Plunge Into the Slums” April, 1917; reprinted: Lewis H. Lapham & Ellen Rosenbush, Editors, An American Album: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Harper's Magazine. New York, N.Y.: Franklin Square Press, 2000. p 205 & 206.

{7} Picryl: “The World's Largest Public Domain Source.”

{8} Edwin G. Burrows & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford, U.K., New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1999. p 587.

{9} ibid, quote and privy information generally, p 747.

{10} Picryl. The panoramic view is composed of individual photographs, composited with minor processing by the author, 2018.

{11} Burrows & Wallace, p 991.

{12} Jill Jonnes, Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and Its Tunnels. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Group, 2007. Trade paperback edition published by Viking Penguin, 2008. p 68 & 69.

{13} Leonard, p 78.

{14} James Guimond, American Photography and the American Dream. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. p 59.

{15} Stephanie Coontz, The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. New York, N.Y.: BasicBooks (division of Harper Collins), 1992. p 11 & 12.

{16} ibid, p 12 & 13.

{17} ibid, p 13.

{18} Leonard, p 7.

{19} Jonnes, p 71.

{20} Mrs. Helen Campbell, with Col. Thomas W. Knox, and Supt. Thomas Byrnes, Darkness and Daylight – or – Lights and Shadows of New York Life. Hartford, CT.: Hartford Publishing Company, 1897. p 485 & 486.

The illustration was available from the Library of Congress; however, a little further “on-line digging” revealed that the entire text is available through the Internet Archive. The wonders of the modern world!

"The Tenement - A Menace to All. Not Only an Evil In Itself, But the Vice, Crime and Disease It Breeds Invade the Homes of Rich and Poor Alike." Udo J. Keppler for Puck magazine, 1901. {2}

{A} The story of the forced sterilization programs during (and after) the rise and fall of the eugenics movement, has had some interest in the last few years. Further information can be had here:

From The Atlantic (on-line): “A Long-Lost Data Trove Uncovers California’s Sterilization Program” Sarah Zhang, January 3, 2017.

From PBS: “Unwanted Sterilization and Eugenics Programs in the United States.” Lisa Ko, January 29, 2016.

From wikipedia: entry on Eugenics in the United States – compulsory sterilization.

{B} Part of the Roosevelt administration's attempts to alleviate the poor conditions in the nation during the Great Depression was the advent of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The FSA's primary goal was to help farmers stay on their lands, to improve those lands through better farming practices, and keep producing crops for consumption. In an effort to stave off criticism of the "New Deal," FSA hired photographers to document the conditions of the nation, and to then document what federal aid had done to help the "forgotten man." Those efforts were broadened to include not only the agrarian's problems, but the difficulties faced by the down-on-their-luck generally, including the lives of mine and mill workers, and their tenement quarters. When the "European War" started and the United States began to ramp up production to supply England and the other soon-to-be Allies, the FSA was brought on-board the "war effort" as the Office of War Information. The photographers kept snapping images until early in the 1940s.

Among the photographers who worked for FSA at one time or another were Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, J. Russell Smith, John Vachon, and Jack Delano and Carl Mydans, some of whose photos are pictured above.

The Library of Congress has amassed a collection of those photographs, and many have been digitized. They can be seen in their on-line catalog of "Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives." There are also color photos, from the companion collection (aptly titled) "Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Color Photographs."

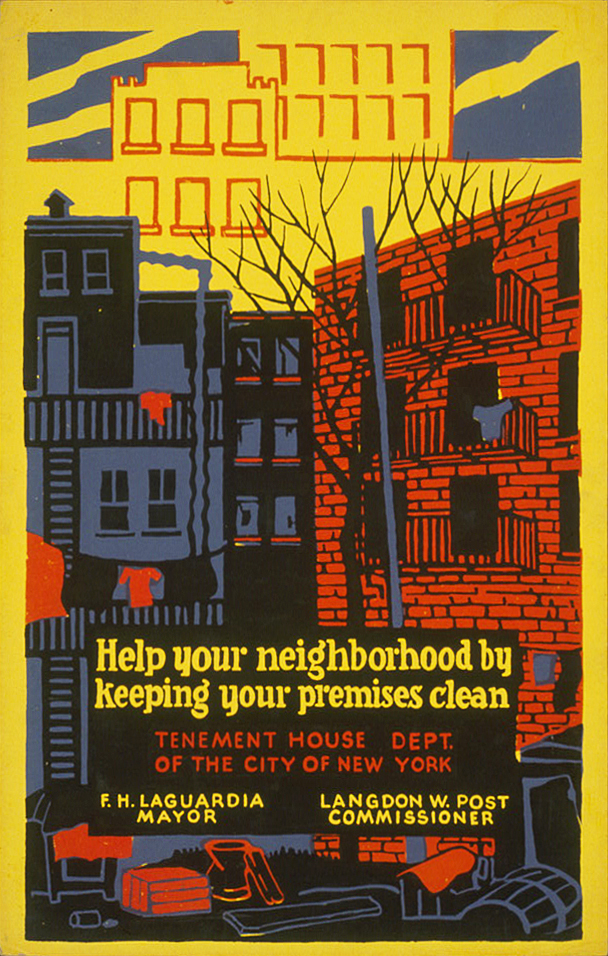

Federal Art Project poster, circa 1936. {2}

And, further reading (like y' do):

Two stories from the 'blog Ephemeral New York; one concerns a "lane" in the Five Points slum, and describes the worst of the worst of the slums; and one about the tenements that are left behind.

Gothamist has a story about how "predatory landlords" are still doing that predatory thing, and this time it includes lead paint-dust.

And while I didn't include nearly as much narrative concerning "urban renewal" here as I started to (an early draft had a pretty fair amount, indeed), a recent story from the Indianapolis Recorder concerning the construction of Interstates 65 & 70 through Indianapolis, Indiana, shows that the effects of that movement are still being felt.