Dreiser, Booth and Speed came up the Lackawanna Valley on their way north, visiting Wilkes-Barre (which I did not this trip) and Scranton. Dreiser wrote: "Scranton is no worse than many another American city of the same size and class that I have seen -- or indeed than many of the newer European cities. It was well paved, well lighted and dull."

What I really liked about his written impression of Scranton is actually more sociological:

"Here again, I could see no evidence of that transformation of the American by the foreigner . . . the peril which has been so much discussed by our college going sociologists. On the contrary, America seemed to me to be making over the foreigner into its own image and likeness." What actually happens to the "foreigners" Dreiser asserts is that they become us: "They gather on the street corners . . . in yellow or red ties, yellow shoes . . . 'style plus' clothes . . . they can't resist the American moving picture . . . the popular song, the automobile . . . "

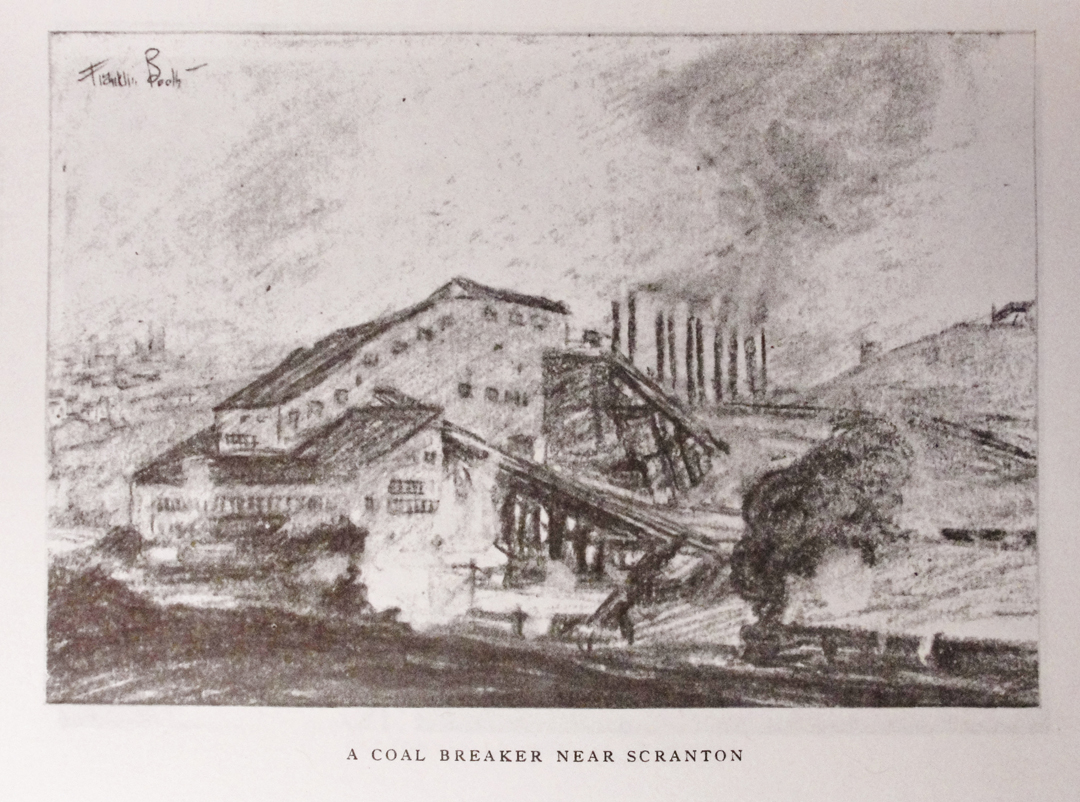

Franklin Booth's sketch of industrial Scranton from 1915.

BUT ANYWAY, on to Steamtown!

"Steamtown National Historic Site was established on October 30, 1986, to further public understanding and appreciation of the role steam railroading played int eh development of the United States." It occupies what had been the marshaling yard and repair facilities of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western (DL&W) Railroad in Scranton, PA.

Like so many railroads that began in some form in the 19th Century, and reached their peak years in the early to mid-20th, the DL&W was one of those major regional carriers moving coal and freight in North-eastern Pennsylvania, Western New York, and Northern New Jersey. When finally it was subsumed by mergers and buy-outs, with the rolling stock changing and updated, the yard in Scranton became a relic, closed by Conrail in 1980.

Illinois Central Consolidation with Visitor Center, part of the Roundhouse complex, behind.

I don't recall when I first heard about Steamtown, but it was "one of those places" that was on the "list" that needed an eventual visit. When still a child living in the Greater Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, I used to visit a portion of Griffith Park called Travel Town: a series of railroad tracks set with a variety of rolling stock and engines from the history of the iron horse empires. My grandfather, among his other pursuits, dedicated some portion of his time to HO gauge model railroading, mostly, I think now, because of my interest in "toy trains." As a hobby for him, it never reached the level of dedication that found an entire basement fitted for a scaled-down world, nor did it rise to the level of perfection that he demonstrated with the large scale, radio-controlled boats that he built from scratch (he did craft some 1:87 scale buildings copied from old mine works in Nevada that were damned fine in detail and workmanship, though). For me, though, the model rails were a source of fun and fascination for several years, and along with my climbing about on the "real thing" in the park, were the foundation of an appreciation for rail travel that still exists.

This immense machine is an example of one of 25 "Big Boy" locomotives built by the American Locomotive Company for Union Pacific just before and during the Second World War.

According to the accompanying placard, "The Big Boys were the longest, and among the largest and most powerful steam locomotives in the world [and were] capable of reaching speeds in excess of eighty mile per hour."

" . . . [the] 412 is 132'-10" long and with a loaded tender weighs 1,189,500 pounds. In service it carried twenty-eight tons of coal, 24,000 gallons of water, and developed a tractive force of 135,375 pounds."

I did a little figgerin' with those numbers not long after I got home; 'cause that's one million, one hundred and eighty-nine thousand, five hundred pounds - or, 594.75 tons of which 28 tons were coal, and about 100 tons of water.

Just for scale - those drive wheels are 5'-8" high. I stand only 4 inches taller.

"At the heart of the park is the large collection of standard-gauge steam locomotives and freight and passenger cars that New England seafood processor F. Nelson Blount assembled in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1984, 17 years after Blount's untimely death, the Steamtown Foundation for the Preservation for Steam and Railroad Americana, Inc., brought the collection to Scranton, where it occupied the former DL&W yard. When Steamtown National Historic Site was created, the yard and the collection became part of the National Park Service."

The Nickle Plate Road's No 44

Across the yard and in several buildings that have been refurbished or repurposed the Park Service now does its best to restore and maintain that collection. It has numerous historical displays concerning the history of the railroads, including the DL&W and its yard; the impact the roads had on industrialization, and how industrialization and mechanical improvements changed railroading; how signals were improved over the years and what they meant to the rail workers; how a steam engine worked and developed its power; some "great" railroad disasters; plus a working locomotive repair facility with viewing walkway; and, among other things, the book and gift shop - where I naturally had to buy a couple things (a postcard book of historic railroad posters and some tin signs).

A view inside the section of roundhouse where engines are rehabilitated. I suppose the Saturday of a 3 day weekend is not the best time to see anyone working on locomotives.

These two photos depict two different types of cars used to plow snow off the trackage.

At left is a giant snow blower, basically: the rotary plow. While not self-propelled, it was self-powered (note the tender coupled to the rear) and probably part of a snow clearing work train, say in Colorado, where "Drifts thirty feet deep through which they must tunnel are not uncommon in the winter lives of these railroaders."

At right would be something a little simpler, the "wedge" plow, though judging from the height of the top shield, probably capable of a great deal of snow throwing.

Both of these plows I have seen in photographs, but never actually imagined seeing them "for reals."

"By the 1930s and 1940s gas and oil were replacing coal as a home and industrial fuel. The DL&W began using diesel locomotives, reducing the need for coal even further. The steam locomotive repair shop in Scranton closed in 1949."

Even as steam locomotive power got "streamlined" in the Moderne era, and advances in technology made ever larger, more powerful engines that were capable of greater hauling, technology was also out-stripping the "iron horse:" diesel power began making in-roads on the rails by the 1940's. While the earliest diesels didn't have the same tractive power of steam engines such as UP's "Big Boy" and even needed steam "helpers" on occasion to make particularly steep grades, the fact that the diesel powered engine was capable of making very long runs without the frequent stops for water and fuel was eventually going to tell. As with most technologies, once it's in use, the engineers (the guys with slide rules, that is) are always going to find improvements - and so the steam powered locomotives would see their last commercial usage by the late 60's or early 70's, and that only on smaller lines.

The UP "Big Boy" and the Lehigh Valley 414, an

ALCO Century 420,

one of 131 engines of this model produced between 1961-1968.

My fascination with rail travel does indeed extend into my adult life. When rail travel makes sense as an alternative to driving, I will buy a ticket. Part of my enjoyment for living in New Jersey was the option, fairly frequently taken, of riding NJ Transit's trains to Manhattan. I enjoyed taking Amtrak from Penn Station New York to Pittsburgh for weekend visits.

Steamtown has excursion trains most weekends. The excursion that ran the day I was there was a relatively short trip (about 6 miles) to nearby Olyphant. Honestly, riding this train wasn't so much about seeing anything, though if I did it would be nice; rather, it was about riding on the rails, pure and simple. It also wound up being about taking a nap - there's just something about taking a nap on a warm day in a railway passenger car with a light breeze blowing through the window. The windows opened!

A 3 car consist made of these old Central Railroad of New Jersey passenger cars made up the excursion train to Olyphant. The photo above shows the exterior which I'm sure has undergone a restoration at some point in time. The baggage door is now handicapped access: there are lifts and elevators available for passengers with wheelchairs and the over-sized door makes their embarkation relatively easy.

Below shows the interior of one of those cars (might even be the same one pictured above), which shows-off the woodwork that once graced these vehicles. Not all of the cars were this nice, but all had some work done to them; this one was perhaps the best example of restoration.

The engines on the excursion train were, alas, diesel, but historic diesels none the less: an F3, built by General Motors' Electro-Motive Division which appears in Lackawanna Railroad livery, and a GP 9 (another GM Electro Motor) - No. 514, built in 1958, and originally on the New York, Chicago & St. Louis, or Nickle Plate Road. They are seen here at the Olyphant station, along with power lines on a series of short poles that appear much like telegraph cables once did:

Sharing the parking lot with Steamtown is the Scranton Trolley Museum (which will have to remain for the time being on "the list" of things to see). Like the railroad excursions, the Trolley Museum runs cars for visitors as well, departing from the same platform, as here:

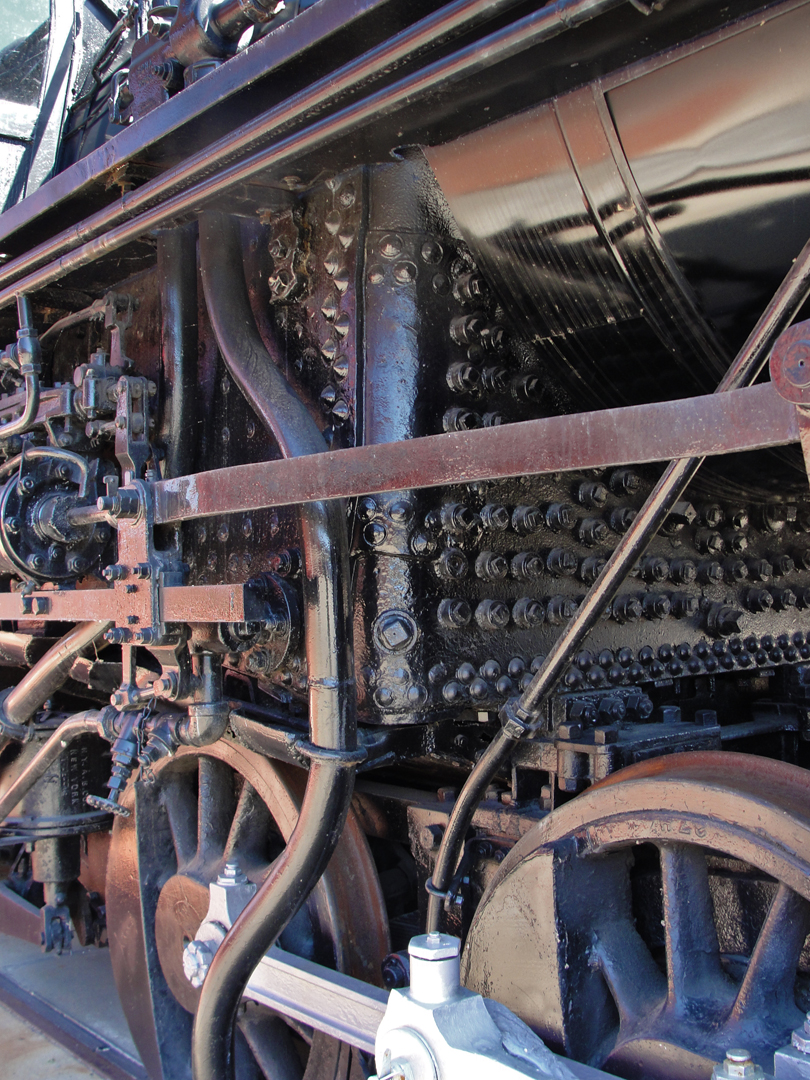

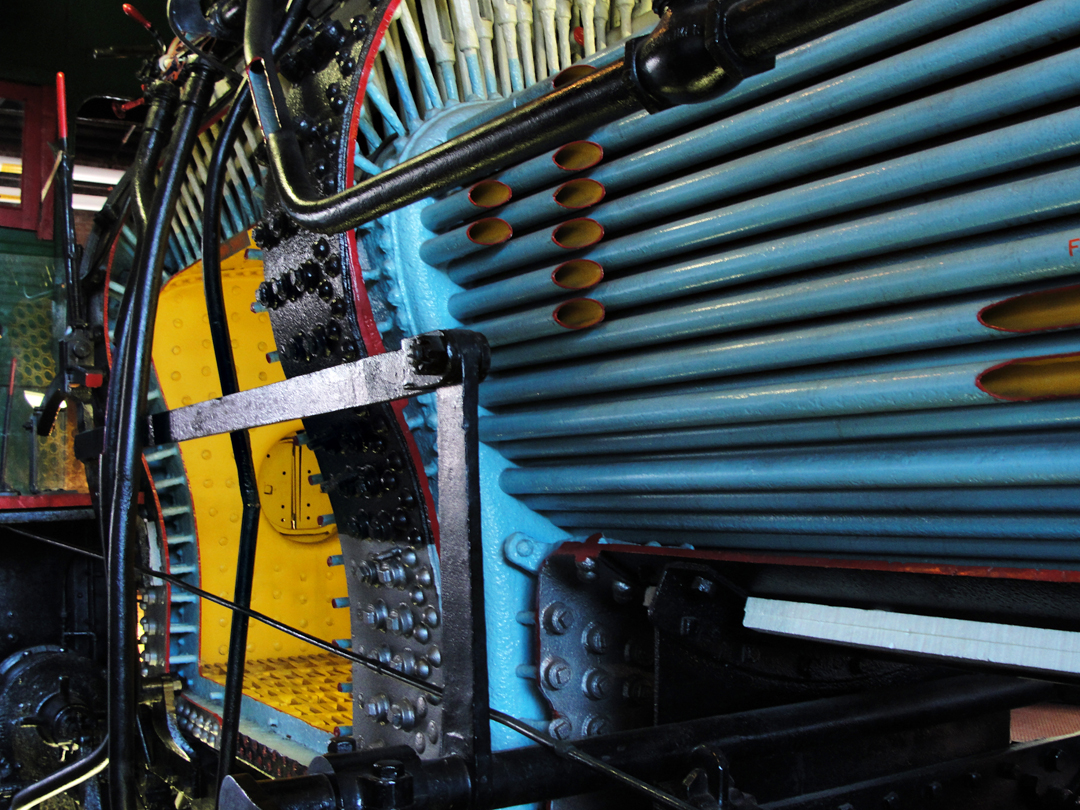

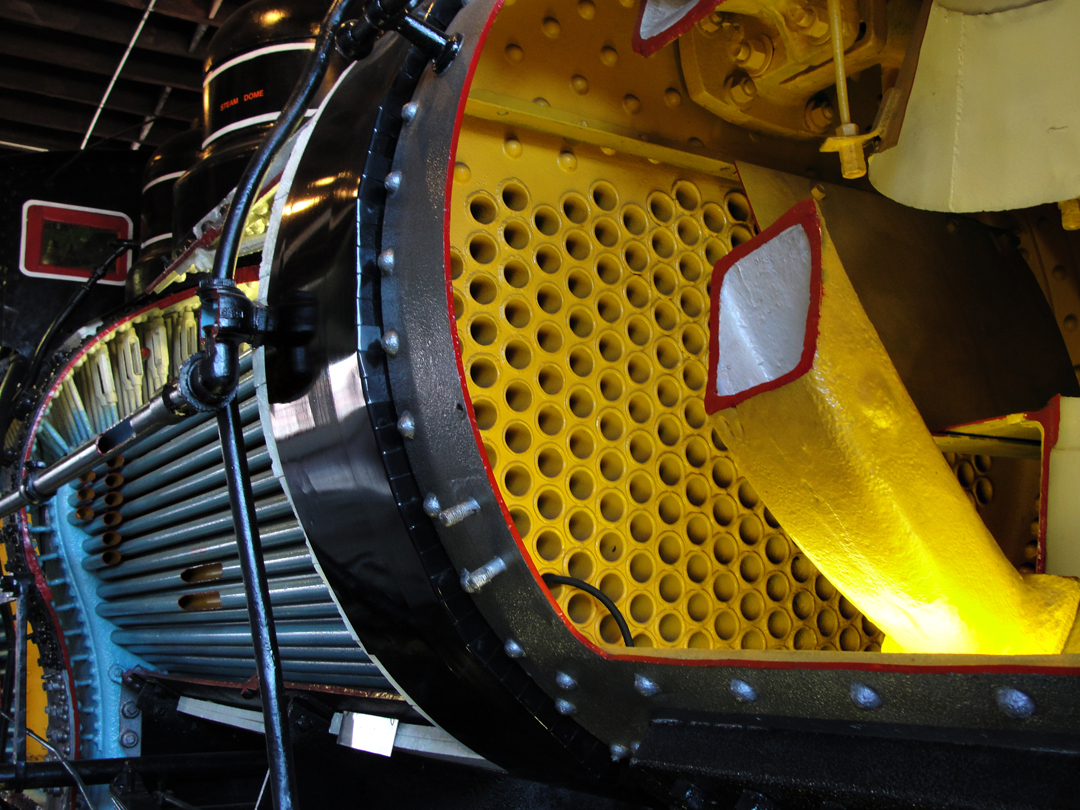

For some time, I've seen "cut-away" views or cross-sections alongside explanations of how the steam engine generated steam power for railroad motive power, but the views and explanations always left something wanting in my mind - I just never quite "got it." The firebox I understood; boiling water I understood; but what all the lines in the boiler were meant to convey? Not so much. I also frequently wondered at the series of bolt heads on the fire box of a steam locomotive, as in the view at left. While I could appreciate that there was a reason for them, I don't think I had seen an explanation - until, that is I found the ultimate cut-away view:

Those bolts are holding the liner of the firebox in place inside the jacket of the engine, and as can be seen (sort-of) in the photo above some have turn-buckles for alignment. The interior of the firebox here is painted yellow; the blue tubes are the heat-exchanging tubes that run through the boiler, and this is where 2-D cross-sections and explanations fell flat in my imagination: I just couldn't translate what the picture and words were supposed to convey. HERE however, it suddenly made sense.

The super-hot air from the firebox passes through the tubing in the boiler where the water is converted to steam. In the photo above the head-end of the heater tubes is shown passing through the boiler end plates to where the now slightly cooled air and smoke from the fire (not for nuthin' is it called a firebox) would be recycled or exhausted. The steam generated in the boiler would pass through valves and piping to be forced through to the cylinders that drove the wheels. Above, a white-painted interior shows in one of the pipes leading to the driver cylinders. As explained elsewhere in the museum, the more work the engine performed, the better its performance as heat built, drafts pulled air through, and steam pressure increased.

All that is what made this Reading Railroad Baldwin "go:"

Unlike this Reading F7 pair. The diesel engine spins a generator which sends electricity to the drive trucks, making the machine move and pull stuff. Nobody has to watch the boiler pressure, there's no messy coal or wood to toss in a fire box, no heat to maintain at a steady temperature -- instead, there's a fuel tank. Plus all the gauges telling the engineer how much fuel he has, and how well his motor is generating, but by comparison it's a "sit down job." I'm sure any engineer would dispute that - there's still a lot to driving an engine, true, but that cab is enclosed now! No more cinders in your eye -- and not much chance of the thing exploding. Diesels also required less scheduled maintenance: once per month, instead of every day.

These units were built for Reading in 1950, one of 4 pair used by that road for passenger consists.

"They powered their first Reading passenger train, the Wall Street, on June 6, 1950. The Reading acquired two more units in 1952, and [they were] in use until the mid 1960's. Due to declining ridership and smaller trains, the pairs were often broken up and used as sole power on a run, except on the Crusader and Wall Street, which still rated two units."

I suppose the irony is that Steamtown is patronized by people arriving by automobile - tourists on their varied drives, like Dreiser, like me, like the other people that were on the excursion to Olyphant. Maybe someday there will be rail access to a railway museum!

A few shots from around the yard.

According to information in the fold-out guide to the site and available in the visitor's center, the yard is "open" to walking about, as long as an eye is kept out: the yard is active, with both Steamtown traffic and marshaling by other local rail operators. At least this day, I was the only tourist wandering the tracks.

The footbridge spanning these two old steamers leads to The Mall at Steamtown.

I didn't go inside that mall. Nope.

Right, and below right: these two pieces of rolling stock show the state of too many - to my thinking - of the cars and engines on site. These alone should be reason enough to demand Congress supply better funding to the National Park Service! This is our history rotting on the tracks!

I miss the crummy at the end of the train. Blinking red lights just don't do it for me.

"I like caboose and I cannot lie..." But - what about the plural? Cabooses? Cabeese? One caboose, two caboose? Got nuthin' and they're all sitting out this run, anyway.

Following my better-part-of-a-day here, I figured I might just as well go on toward Buffalo. All the roads recommended to Dreiser and Booth took them out of Pennsylvania and up to Buffalo before heading West, so since I had determined at this point that I might as well do this "test run," it was to Upstate New York I went.